Because graphic novels combine story, pictures, and words, it’s rare for one to excel in all three. Anneli Furmark‘s Red Winter is that exception. Though one of the most acclaimed graphic novelists in Sweden, Furmark is a newcomer to most English speakers. While I hope Drawn & Quarterly will translate and publish more of her work in coming years, Red Winter is a remarkable introduction to this artist-writer.

It’s also an intimate window into a complexly compelling period of Swedish cultural and political history. Though Drawn & Quarterly’s back cover blurb provides the basics — “Passion and politics unfold against the darkness of winter in 1970s Sweden” — Furmark is far less direct, preferring to drop her readers into not just a historical moment but the minutia of her cast’s interlocking lives. Translator Hanna Strömberg kindly glosses the most obscure references (the APK is a Marxist-Lennist party not to be confused with the Maoist SKP or Sweden’s largest Communist party, the UPK). Though I suspect some readers will, like me, have never heard of “Bohman and his cronies” or their so-called Moderate Party — which, happily, is not a problem since Furmark provides just enough clues in her dialogue to ground the situations. Further, rather than penning in clunky dates in caption boxes, she let’s the music do the talking—as when the teen son blasts Deep Purple’s 1972 “Highway Star” from his bedroom stereo.

Furmark divides her novel into nine chapters, ranging from 11 to 36 pages, each titled after a character: Siv, the main character who is having an affair with Ulrik, a sincere but inept member of the APK as it tries to gain influence in local unions; Marita, Siv’s pre-teen daughter who reads her mother’s diary when not playing in puddles outside; Peter, Marita’s older and adolescently angsty brother; and last and least Borje, Siv’s well-intentioned but clueless husband who works at the mill where Siv is trying to recruit. There are more—Marita’s best friend, Ulrik’s best friend, Peter’s car load of terrible friends, and of course the tale’s only antagonist, the self-important local APK leader Peter who ultimately ruins Ulrik and Siv’s future in a fit of political paranoia. But while thIS may sound like a lot in summary, the movement between and through scenes is seamless and the tracking of characters effortless as Furmark immerses her readers into the vibrant milieu.

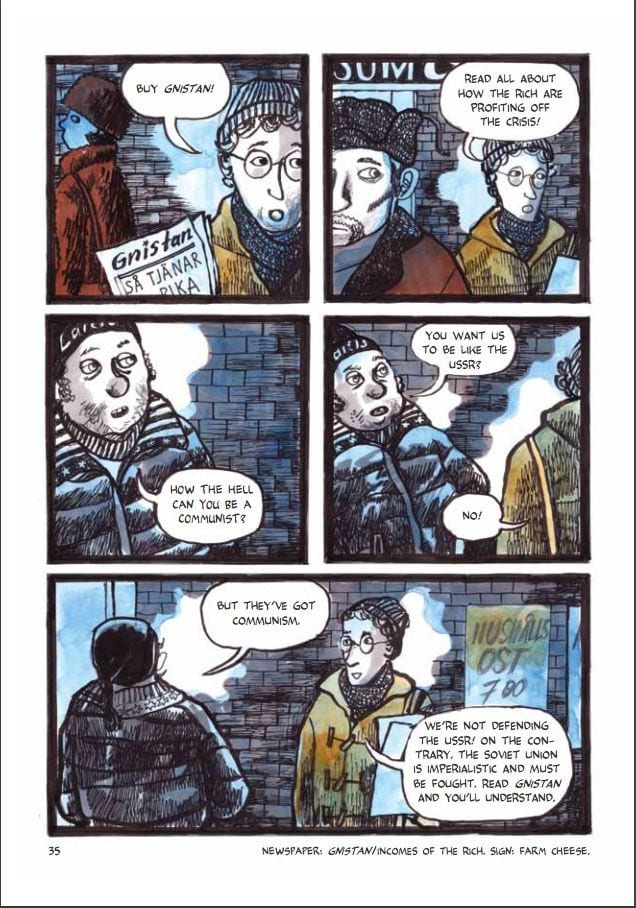

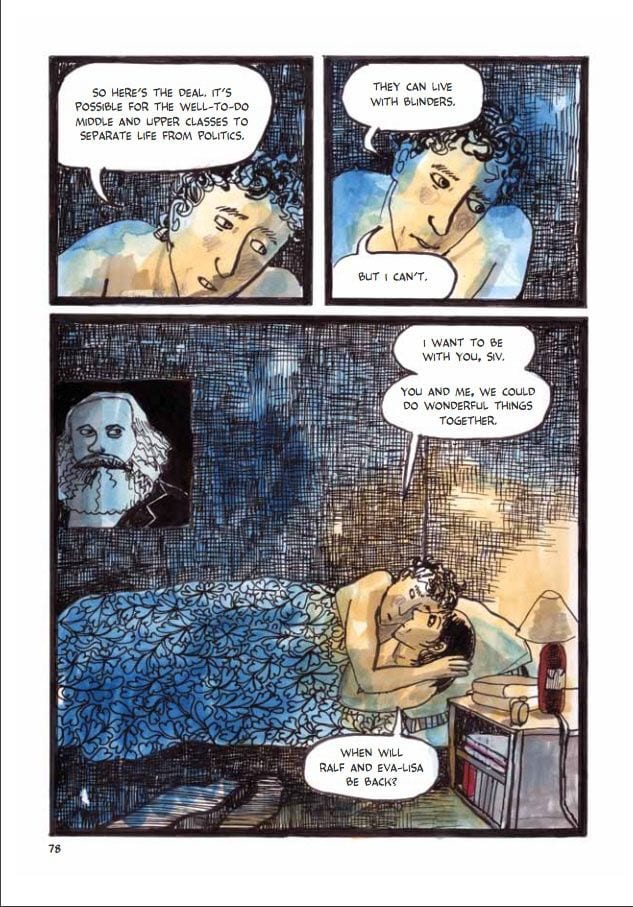

The complexities of her interwoven plots are offset by a deceptively simple visual style. Her characters are cartoonish in the simplified sense, their faces rendered with a minimum number of pen strokes. But their world is darkly patterned and crosshatched, and Furmark layers watercolors over her line art for unexpected effects, often violating divisions between foreground and background, so the color of a character’s face or body envelopes them into surrounding walls or street scenes. Furmark also draws unusually thick, black frames around each of her panels. Combined with the rigid gutters of her always rectangular layout, the visual style reinforces the sense of isolation plaguing each character.

While many graphic novelists combine art and storytelling for excellent effect, the language of graphic novels can be comparatively lacking. But Furmark—at least as translated by Stromberg—wields her keyboard as carefully as her brushes. The novel opens with a kind of prose poem—though really Siv’s meandering stream-of-consciousness as she muses about secretly meeting Ulrik. A few chapters later after she’s snuck out of Ulrik’s commune, Siv reflects on her own passing thoughts, calling them “almost a poem”. The self-consciousness is a right fit for her character, someone longing for romance and escape, but never able to achieve either.

Furmark also gives glances of Siv’s diary and, when discovered by the snooping Peter, Ulrik’s, imbuing the passages with distinct verbal qualities linked not just to the characters but to their specific letter-like reveries. The contrasts are further heightened by an excerpt from a published book of poetry and the song lyrics Marita sings to herself. Furmark also achieves subtleties in her dialogue, as when Borje complains to Siv about all of the competing Communist parites, “we should stick together … instead of splintering up all the time,” while unaware that his wife is about to leave him. Like Furmark’s inks and watercolors, her word palette is equally striking despite its surface casualness.

Much of the novel’s work is accomplished between chapters, with key scenes and ultimately the story’s saddest outcomes occurring off-scene, requiring readers to imagine what is only glancingly referenced while Marita and her best friend wander outside in their rainboots. It’s an especially apt approach for a graphic novel, since the comics form is largely defined by the content implied between each of its juxtaposed images. So again, Furmark demonstrates the excellence of her art. Red Winter is a window into not only Sweden in the ’70s, but to an alternate comics tradition defined by subtle craft and storytelling.

I look forward to more of Furmark’s translations.