In the first episode of Bates Motel, the not-yet-infamous Norman Bates (Freddie Highmore) and his mother Norma (Vera Farmiga) find themselves in a rowboat, preparing to dump a corpse at the bottom of a lake in the middle of the night. In this anxious and dramatic moment, Norma offers an observation that no one can possibly expect from horror’s most iconic mother: “I suck.”

The scene juxtaposes conventional horror and surprising slang, melodrama and creepy humor, demonstrating a couple of ideas in A&E’s new series, which chronicles the evolution of this most disturbing of mother-son relationships. First, the series hews close to its roots, both Robert Bloch’s book and Alfred Hitchcock’s movie, Psycho, delivering both a grisly murder and a watery grave in the premiere itself. Second, this series is an entirely contemporary affair, set in 2013. Norman goes to high school, Norma runs the motel. They might be your neighbors.

Can this work? Can we imagine this thoroughly cool and girlish mother becoming the terrifying monster who controlled Norman’s every breath even after death? Can we believe that Norman might ever have been (or be) a kid who texts with girlfriends on his iPhone? As of the end of this first episode, these questions remain unanswered.

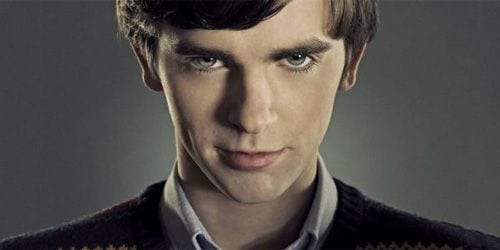

Beyond and before that, Bates Motel is good, a complex and chilling drama with an enticing and essentially odd appeal. Even in their new timeframe, Norma is familiarly demanding, passively and otherwise, and Norman is as nervous and eager to please as you’ve seen him before. Highmore evokes memories of Anthony Perkins’ Norman, the handsome and shy one who vaguely flirts with Marion Crane, with just a hint of fiery rage behind his eyes. He is humble and tongue-tied with his new classmates (he and his mother move from Arizona following his father’s untimely death at the series’ start), but he’s capable too of trashing his room and sneaking out to a party where the DJ plays Radiohead. He longs for his own voice, but is also that loving son who wants to do the right thing as his mom defines it.

That mom is here young, blond, and even sexy. Farmiga gives Norma multiple layers, from the supportive, genuinely loving mother to a brutally manipulative Lady Macbeth who uses reverse psychology and twisted logic to convince Norman that his obedience to her is only sensible. Norma believes her own stories, that victims deserve what they get, that her ends justify her means; mother and son do have a new business to run, after all, and so she insists they keep focused — on each other. Her clinical scheming supports the hint (though it is just a hint) that this may not be her first foray into murder and deception (we’re not really sure what or who killed Mr. Bates). The show follows Norma’s own moods and processes, transitioning from unsettling psychological mystery to a familial saga as Norma rationalizes her actions. It also follows Norman’s efforts to live apart from his mother, a process that looks doomed to failure.

Bates Motel isn’t Hitchcock, and doesn’t try to be. But the show does make intelligent use of what you already know about Norma and Norman in their efforts to “start over,” as she says repeatedly. And it works up a suspense all its own: we worry that this duo will be caught (and what fate might befall those who “catch” them), and we worry that they won’t be caught, that the dread — ours and theirs — will go on. Like Hitchcock’s movie, the show uses moody lighting to suggest Norman and his mother’s internal states: as he contemplates what’s just happened or what might, he appears in shadows and dark blue glows, the latter cast by the neon sign his mother has put up, because blue is his favorite color. As in the film, the attraction here is Norman’s (and now Norma’s) multiple facets. How does a teenager hoping to improve his Language Arts grade turn into a young man who believes, “We all go a little mad sometimes”?

Not merely “That Psycho Show,” Bates Motel offers a multilayered mother and her son, who is, after all, a lot like other teenagers on television today, a kid with a secret. But though his mother insists, “As long as we’re together nothing bad can really happen, right Norman?” we know otherwise, that this secret is very bad. And along with him, we may be at once frightened and intrigued.