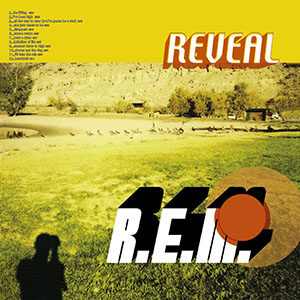

R.E.M.’s 12th studio album, Reveal, turns 20 on 14 May. Although typically known as the band’s return to their “classic” sound after their electronic experimentation of Up, it has a staying power all its own. More than that, it’s far more than just another R.E.M. album. While it has the atmospheric—and almost eerie—Americana sound that the group is known for, it also features the synths they missed out on in the 1980s, when they played around with dynamics. There are no jarring volume changes here, either, as the whole album is as smooth as a river rock.

Despite this fluidity, Reveal retains the classic R.E.M. eccentricity. It’s “classic” not purely in sound but also in spirit, willing to draw together disparate elements that shouldn’t work alongside creating its own. Here, the group takes turns channeling Westerns, space operas, 1980s/1990s ballads, and 1960s pop, all the while having no qualms about mixing it all together. That’s not to say that the group throws everything in a pot and watches it boil down; rather, everything is added in very deliberate quantities and very deliberate places (in true hyper-intellectual R.E.M. fashion). Additionally, it’s unafraid of minor risks—such as vastly differently scored verses and choruses—effectively making a calico song of two tracks.

Lyrically, it’s relentlessly and drily optimistic, invoking the kind of melancholic cheer shown by a parent watching their child grow up. As is typical of R.E.M., there’s fairly little storytelling; instead, they focus on evocations of mood that, in turn, tell stories of their own. The LP also displays a significant maturation of Michael Stipe’s voice and lyrics. While he’s never been known for vocal virtuosity, he proves that some simple practice works miracles, as well as that R.E.M.’s two decades of existence had done its work.

Album opener “The Lifting” features spacey synths in tandem with lyrics like, “You said the air was singing / It’s calling you / You don’t believe these things / You’ve never seen, never heard, never dreamed”. Odd off-beats in the vocal line further the unearthliness of the track, and the soft yet suspenseful tapping percussion rounds out the instrumentation.

Afterward, an ’80s influence is particularly apparent on “I’ve Been High”, with soaring keyboards and emotional, nearly ballad-like lyrics such as “Make my make-believe believe in me”. Throughout, there’s a certain spangly percussion present that’s kind of tongue-in-cheek. Instrumentally and lyrically, it reads like a loving parody of a certain genre of ’80s music.

In a bouncy and bassy recreation of Western music, “All the Way to Reno (You’re Gonna Be a Star)” features the addition of bubbly synthesizers and a delightful guitar riff to close out the verses. “You know what you are / You’re gonna be a star”, says Michael Stipe. Whether it’s genuine or sarcastic, he slams you in the face with his quiet sincerity.

Next, “She Just Wants to Be” begins with acoustic strumming, patiently growing as new parts are added. While it’s a spare piece (it’s effortless to hear the different instruments), the gentle power of the gradual build, coupled with the utilization of negative space around the bridge, distinguishes it from the pack.

The fleeting chaos of near noise starts “Disappear”, whose verses feature a Nick Cave-style tension akin to the sensation of counting down on your fingers. The chorus is only slightly more upbeat, featuring the lyrical refrain of “I looked for you everywhere”. On top of being one of the strongest displays of Stipe’s vocals, it also features some of the most painful and affecting sentiments (“Erasing all I’ve been” and “I came to disappear”).

“Saturn Return” contains gentle piano—in turns hesitant and confident—paired with a spacey synth that could be right at home scoring old school Doctor Who or on a later Blur album. You can perhaps hear its echoes in such acts as Broken Bells and on the Rentals’ 2020 album, Q36, and arguably just about any other contemporary space rock (like Bowie rewritten for the twenty-first century).

The almost 1960s-sounding “Beat a Drum” is anachronistic with its soaring, nearly Pet Sounds/Sgt. Pepper’s-esque chorus instrumentation paired with Michael Stipe’s distinct vocals. The verse guitar is particularly spangly, perhaps even early Kinks-like, especially when supported by the shining, watery keyboard.

“Imitation of Life” is pure R.E.M.—jangly guitar paired with nearly humming tenor vocals in a near-rewrite of “Losing My Religion”. More than that, lines like “The greatest thing since bread came sliced” and the chorus of “That sugarcane, that tasted good / That’s who you are / That’s what you could / Come on, come on, no one can see you cry” beg to be screamed along to at a concert, with the ferocity typically reserved for college-aged Mountain Goats fans.

“Summer Turns to High” combines ’60s and ’80s sounds and recondenses them as turn-of-the-millennium indie. Stipe sings as gently as a lullaby while the percussion and synthesizers don’t so much stab as prod (like the mechanisms of a clock), matching the nearly counting-aloud rhythm of the vocal line.

“Chorus and the Ring” is cheerful, kind, and rich as ice cream, thanks in part to its warm and clever bassline. Here, noisy feedback sounds like home and safety; even as it drowns out Stipe’s voice, you can’t bring yourself to care that much.

Stipe’s voice comes out thin and weak at the beginning of “I’ll Take the Rain”, matching the despairing lyrics. However, at that point, the instrumentals (well-developed, if not particularly strong) hint at the cheerful nihilism of the upcoming chorus. It pairs self-empowering but melancholic lyrics with optimistic instrumentation and vocals, yielding a sound like sunlight filtering between clouds on a rainy day.

“Beachball” is another baroque pop-sounding track, so much so that I double-checked the personnel list (swearing I’d heard a living, breathing horns section) only to find it was simply clever guitar and keyboards. The combination of lyrics recounting a beach day and the nearly vaudevillian “horns” recall the inexplicable, sundrenched sadness of the cultural memory of a Coney Island weekend, even for those of us who never went.

The album itself is a careful collage of disparate sounds that are never cluttered or nonsensical, just as it’s an assemblage of songs that—superficially—have little to do with each other outside of literally sounding like R.E.M. in the 21st-century (post-Up). The tracks, like the album, self-define their status. “Imitation of Life” comes between “Beat a Drum” and “Summer Turns to High”, just as Reveal itself comes after Up. The overall effect—of the disparate sounds and the self-definition—is one of conscious and wholesome blankness. It does not try to be more than it is.

Yet, this really is just a guitar rock album (which isn’t a bad thing because it’s very clever, especially because it never wants for any other instrumentation). Utilizing esoteric timbres is often considered an innately good thing for an album to do, but R.E.M. can create the effects of those instruments while “only” using guitar, bass, percussion, keyboard, and vocals. (Granted, keyboards can do a lot of heavy lifting.)

Maybe you can hear its influence in some places; however, that’s not the important thing. After all, an album doesn’t have to be influential to be special. It is, though, more than just another R.E.M. album. Whether or not it’s their best is up to individual interpretation, but it certainly holds a particular maturity and balance unique to their oeuvre. Perhaps this maturity comes from its own awareness of itself as a good album and nothing more. Sometimes, something doesn’t have to be special to be special.