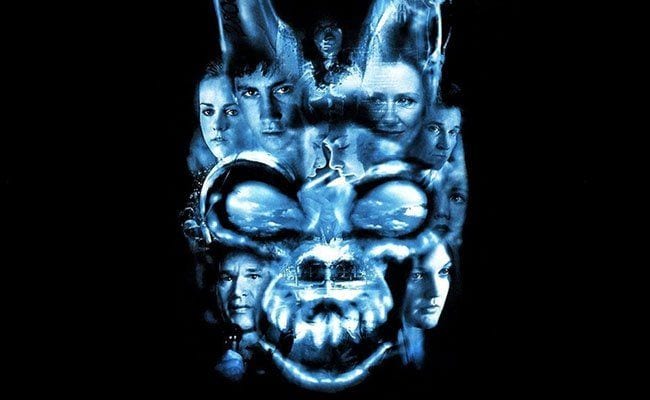

In 2001 a very strange and surreal movie called Donnie Darko was released into theaters to very little fanfare. This obscure and dark tale about a 1988 teenager with a rather casual relationship with normalcy didn’t make a big box office splash but whispered its way into history when word of mouth made Donnie Darko a cult classic.

Writer/ director Richard Kelly certainly had high hopes for the film but didn’t exactly expect its posthumous success. In my interview with Kelly, surrounding the 15th anniversary theatrical re-release of the fully restored film, the artist is amazed and fascinated by the fandom that has surrounded his film. “It’s great. I’m so grateful that people are supportive and that they still want to talk about this movie and that they’re excited to see it on the big screen,” Kelly tells me. “We spent a lot of time with this restoration and we wanted to get it right and we wanted to make sure the image was restored and preserved and… here we are, you know?”

Indeed, much of the mystery surrounding Donnie Darko involves its resurrection after its initial lack of success. “So few people have ever seen this movie on the big screen and it’s a whole new experience, that’s for sure.” Kelly says, thrilled. “It only made…” he calculates in his head “five hundred thousand dollars at the box office back in 2001 and so it was a failure at first and it’s become a huge success over time. I think that part of what I’m excited to communicate to people is that it’s a mainstream film now.”

A huge success indeed — enough to demand a 2004 theatrical Director’s Cut release as well as the new restored version in 2017. Donnie Darko is still one of the most puzzled over and debated cult films of all time. With its bizarre take on time travel, ghostly six-foot rabbits, literary discussions of Watership Down, satires of the self-help industry, intellectual explorations of Smurf sexuality, not to mention a dark soundtrack of surprising ’80s songs, it’s certainly an unlikely hit and the exact kind of movie that film buffs are thrilled to see succeed.

That said, it’s strange to hear the word “mainstream” come out of the mouth of director Richard Kelly, especially as his next films were the surreal Southland Tales (2006) and the firmly cemented into the strange The Box (2009). However, “mainstream” is one word that continually comes up during my conversation with Kelly.

“I love and I’m honored to have the word ‘cult’ assigned to any of my work. That’s a badge that I wear proudly.” Kelly says. “But I think, as artists, we all want to push as far into the mainstream as possible because it gives us more resources to work with, to realize these stories on a much grander scale and so I’m happy to try to push Donnie Darko into the mainstream. And I feel like we’ve arrived there, I do. I feel like everyone’s heard of it, and it wasn’t always like that.”

As our conversation continues, it becomes clear that Kelly’s approach to the mainstream is not about selling out, taking studio assignments and formulating popcorn motion pictures to appeal to the masses and break into the top ten. Much as Donnie Darko claimed widespread fame by defying both convention and expectation; Kelly is fighting to bring the mainstream to him on his terms.

“Maybe someday I’ll figure out how to divest myself emotionally from something, but I just don’t know how to do that yet,” Kelly muses. In spite of the lag between his personal films, Kelly hasn’t been resting on his laurels. In addition to his hard work on the Donnie Darko restoration, “I’ve been working on a lot of different projects, and they are very ambitious. And they need a certain budget, you know? They need enough money to be realized to their full potential. It’s a whole process of getting all of the elements in place. It takes a long time. It’s kind of like threading a needle while riding a roller coaster sometimes,” Kelly laughs. In fact, there are so many films in the works, it’s difficult for the writer/ director to know which one is next. “I’ve been writing for so long over the years that I have so many projects prepared that it’s now us figuring out which one is going to be the first one out of the gate. And hopefully once that one’s out of the gate, there will be several more that happen immediately thereafter. I wish it didn’t take this long but it’s just that these are really complex movies to put together.”

That’s where the sleeper success of Donnie Darko comes into play for Kelly. His independent spirit, coupled with his grand ambitions to make epic and fully realized films, has caused him to approach Hollywood on his own terms, but also play the game by his own rules with the hope of obtaining more immediate box office numbers. “I’ve never had success theatrically. I’ve never had that big opening weekend or that big per-screen average. I look forward to maybe that happening one day. My movies have done very well in home entertainment. Over time they’ve done very well and so I think, if anything, we’re just trying to make sure that the next one has all the elements and the recipe for success because having the box office is very meaningful in terms of being able to raise money.”

Similarly, as affable as Kelly is to talk to, and he is, he remains very closed-lipped about what those upcoming projects might be. To be sure, Southland Tales is a vastly different film from The Box and both are very different from Donnie Darko. “I feel like each movie is its own organism and there are fans of each movie,” Kelly says. “I’m focused on trying to stay original and do my own ambitious stories. I think that’s what I’m focused on: building my own sandbox. And I think these movies are more connected than people realize. They’re all part of a bigger story and a bigger universe, ultimately, that I’m trying to build and focus on.” That’s about as specific as he gets.

One potential exception to Kelly’s rules is the single film that he wrote for another director to helm. That film was 2005’s Domino and that director was Tony Scott. At this point, Kelly becomes both very excited to talk about this project and very sad about the reception it received. “That was a wonderful experience,” Kelly gushes. “I wrote that for Tony Scott. That was Tony Scott’s very personal project that he had spent eight years developing with Domino Harvey, a close friend of his and almost like a daughter to him. He had spent years trying to tell her story and so that for me, it was an honor for me to get to work with Tony and to write that script for him and to design this really elaborate puzzle for him to tell her story. So that was just a privilege.”

Kelly did more than write the surreal screenplay; he also became close with Scott, much as the film’s namesake did. “I spent two years working with Tony on that film and I learned so much from him,” Kelly remembers affectionately. “He was always ahead of the curve and pushing into new territory. He was just a workhorse. He worked so hard and he lived to be on set. If you got to be on set with him, that was just a lifetime experience.”

Kelly marvels at the career of the late Scott. “I feel like he never got the respect that he was due. His films all gained appreciation over time.” Specifically on the subject of Domino, “I feel like he was ahead of the curve and he was ahead of his time in a lot of ways. The techniques he pioneered on that film with all the hand-cranked cameras and the stroboscopic editing and the Bursinger film stock and the cinematography and the sound design and the music”, Kelly lists with amazement, “I mean that movie was an overwhelming experience for people. I think those techniques you [now] see adopted in a lot of other films, television, commercials,” Kelly goes on “I have great, fond memories of [Domino] and I hope that people can rediscover that film and see what he was trying to accomplish because it was unique.”

Of course, there is a precedent for this hope in Kelly’s career, specifically the subject of our discussion today, Donnie Darko. “The movie was not well-received when it came out and I’m just grateful that anyone appreciates my work and I’m just committed to trying to get better and become a better filmmaker and stay focused on telling my own kinds of stories. I wish I could make movies with more frequency and I hope that will be the case moving forward. There’s been a lot of planning and a lot of work done already, so we’ll see what happens.”

Similarly, Southland Tales achieved a wider audience on home video. “There are a lot of people who have discovered Southland Tales and I think that with the election of Donald Trump, there’s all this new meaning invested in it now,” Kelly laughs. Indeed, the 2006 film does depict a strange and surreal time in an alternate United States in which Hillary Clinton is seeking the presidency amid right-wing politics running amok and foreign influences reaching throughout the country while even the news becomes untrustworthy.

Kelly is candid about the successes and the failures of his career and especially the failures that have become successes. There is, however, one subject that is the result of his success that he is loath to discuss: the direct-to-video sequel called S. Darko (2009).

“I hate it when people ask me about that sequel because” he laughs, morosely, “I had nothing to do with it. And I hate it when people try and blame me or hold me responsible for it because I had no [involvement]. I don’t control the underlying rights to [the Donnie Darko franchise]. I had to relinquish them when I was 24-years old. I hate when people ask me about that because I’ve never seen it and I never will, so… don’t ask me about the sequel.” He adds with a cynical laugh, “Those people are making lots of money. They’re certainly making lots of money.”

I agree to avoid the subject of “that” sequel, but fans of the film have been asking for years what a “real”, Richard Kelly sequel to Donnie Darko might be like. Does Kelly consider the story to be finished or will there ever be an official sequel?

“I’m open to doing something much bigger and longer and more ambitious that could be a new story,” Kelly says, thoughtfully. “I started this restoration to restore and preserve the integrity of both versions of the movie that exist… I just want to protect the integrity of it and I would never want to do anything unless it was a new, worthy story to tell. I would never want to do something for the wrong reasons or let it fall into the wrong hands.” When it comes to protecting the franchise, he does draw one specific line in the sand. “More than anything, I just don’t want anyone to ever remake it or do something cynical,” he says firmly, then more optimistically adds, “We’ll see what happens. I have a lot of stuff that I’m working on and it’s ambitious and it’s expensive and we’ll see what happens.”

All of these projects within Kelly’s sandbox, whether directly related to Donnie Darko or not, rely on a great deal of fundraising to, as Kelly puts it, realize them to their full potential. This naturally leads me to revisit the questions of how Donnie Darko in its original form, came to be funded and made in the first place. The cast alone, filled with recognizable faces including Jake Gyllenhaal, Jena Malone, Drew Barrymore, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Mary McDonnell, Holmes Osborne, Katharine Ross, Patrick Swayze Noah Wyle, Daveigh Chase, Beth Grant and a young Seth Rogen surely must have cost money. The special effects are beautiful, and that doesn’t even touch upon the licensing of the original songs, which are characters in the film themselves.

Like the film’s eventual ascendancy, its birth also relied on a lot of great luck. “Well the budget was $4.5 million in the year 2000,” Kelly tells me, “and that was barely enough to pull it off. We probably needed ten, but we got $4.5.” He laughs. “It was when Drew Barrymore signed on and agreed to play the English teacher that her star power allowed us to raise $4.5 million. When she committed to playing that role it helped get the other actors to agree to work with a first-time director like me. She validated me as a filmmaker,” he says with audible gratitude in his voice. “All the actors worked for scale and we shot in 28 days on a really tight schedule in Los Angeles in the summer of 2000.”

Belief in the film went a long way. Kelly had his script and a cast of promising and recognizable faces to help bring that script to life. Movies, however, also need a crew. “I believe there was a commercial strike, so there was a lot of crew available that wanted to stay in LA,” Kelly tells me. Because of these serendipitous events “we were able to pull it off in 28 days in Los Angeles [and] surrounding Los Angeles. We were able to get very creative.”

Luck is one thing, making things happen is something else. Kelly relied on both luck and skill to bring his soundtrack plans to life. Kelly tells me he cut together sequences from the movie using the music of bands like Tears for Fears, INXS, Echo & the Bunnymen, The Church, Duran Duran and Joy Division and presented the footage to the bands as if they were music videos. “We sent the footage to the bands and I think when they saw the footage they didn’t want to deny us the rights. They saw how special it was,” he tells me jovially. “And I’ve also been pretty brazen to convince a producer to let me shoot all of these sequences without the song rights,” he laughs.

Kelly continues to muse on how fortunate he was to get these great songs for his film. “I think that most musicians are hippies and they’re bohemians at heart and they tend to be pretty generous. As long as they see you’re not abusing their music or embarrassing them,” He laughs as he elaborates “You know, putting their music in a poor context or tasteless context… They tend to be cooperative and they want to help out.”

And help out, they did. The music helped to make both versions of Donnie Darko more haunting, memorable and original. The songs integrate beautifully with the score and mesh wonderfully with the action in the very “music video” way Kelly designed them.

Donnie Darko Official 15th Anniversary Trailer

Still, as Kelly said, he would have preferred a larger budget to more fully realize his ambitious vision. “There were a lot more practical effects and visual CGI effects that I wanted to do, particularly in the climax and the time travel sequences in the end of the movie. But I think we did pretty well with what we had.” As with his plans for future films, Kelly keeps the unrealized parts of Donnie Darko close to the vest without revealing exactly what those might have been.

There are many rumors out there, including certain superpowers that the title character might have. “Yeah, there’s a bit of a superhero narrative implied.” Kelly laughs with tongue planted firmly in cheek. “There’s the question of how is he able to get the axe in that bronze statue? How is he able to break into the school? There’s the insinuation that perhaps he does have some abilities that are, um… that are new.”

Perhaps that’s an additional key to Donnie Darko‘s success. Kelly tends to ask more questions than he answers, on and off the screen. Just as his characters debate Smurf sexuality, Graham Grene’s The Destructors, Time Travel and Richard Adams’ Watership Down, fans of Donnie Darko have now had over a decade and a half to debate this enigmatic film.

“So, yeah, you know, again, I’m just honored that people have such an affection for this movie and [that appreciation] took a while,” Kelly says. While he’s proud of all of his films and his future projects alike, Kelly, like his fans, holds a special admiration for his first studio film and he does not resent, in the slightest, being known for Donnie Darko.

“Donnie‘s been around the longest and it could be that I go through my whole career and I finish my whole career, hopefully as an old man, and people will still look back and say I never made a film as memorable as my first one,” Kelly tells me proudly. He thinks about that briefly, then adds with a smile in his voice “And, you know? I’m fine with that.”