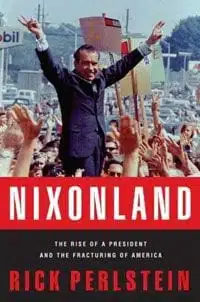

Rick Perlstein’s new book, Nixonland, is the “It” history book of this publishing season. The Chicago historian’s 800-plus-page account of how Richard Nixon stoked and exploited the political divisions of the `60s has struck a nerve, as analysts argue over whether Nixonland — a country at war with itself — still resides in the heart of the US of A.

In a recent lead New York Times Nixonland review, conservative commentator George H. Will protested that “The nation portrayed in Perlstein’s compulsively readable chronicle, the America of Spiro Agnew inciting `positive polarization’ and the New Left laboring to `heighten the contradictions,’ is long gone.”

Maybe. But if you’re a boomer who lived through the 1960s, Nixonland will induce scary flashbacks to that profoundly disorienting time, when university students protesting the Vietnam War were shot dead by the Ohio National Guard; when academic researchers working late were blown apart by bombs spliced together by anti-war radicals; when the Newark police force mowed down dozens of black residents with a hail of bullets; when Alabama Gov. George Wallace, referencing a protester who had lain down in front of President Lyndon Johnson’s limousine, promised that if he were elected president, “the first time they lie down in front of my limousine, it’ll be the last one they’ll ever lay down in front of because their day is over!”

Through this chaotic tapestry, Perlstein threads the story of Richard Nixon himself. Perlstein’s thesis: Nixon brilliantly exploited the country’s hates and fears in the service of consolidating his own political base.

Perlstein, in Seattle recently to read from Nixonland, described his obsession with a decade that was almost over before he was born (in 1969). A fellow with the liberal Chicago think tank Campaign for America’s Future, Perlstein says he didn’t choose his topic so much as “it chose me.”

As a kid, he bugged his parents for stories of the 1960s. “I couldn’t believe the drama, the conspiracies,” he said. “I was fascinated, not by the minivan commercial version of the 1960s, the version where everyone grew their hair long, rioted, then moved to the suburbs,” but by the terrifying, violent reality, when the left and the right regarded one another with a kind of “murderous rage.” “It wasn’t fun,” he says. “It was traumatic,” and its legacy shaped American politics the way the Civil War shaped US history for decades to come.

Perlstein says he’s still perplexed at the depth of the antagonism Americans grew to feel for one another, especially in the wake of the 1950s, an era of unparalleled peace and prosperity. “Postwar, the country was rich, prosperous, confident; it created an attitude of `we can solve any social problem,'” he says. Policymakers and pundits believed in “unlimited possibility and potential,” constructing wildly optimistic scenarios of victory in Vietnam and the end of poverty, and shrugging off moral codes that had held fast for generations.

“The `60s became a period of such dramatic excess. People on the left were quite casual about ignoring the intellectual and psychological cost of rapid social change,” Perlstein says. “It was a very condescending, arrogant mind-set. When the backlash came, liberals were blind-sided. That made the counterpassions even more intense.”

The backlash enraged and bewildered Johnson, who regarded the federal War on Poverty and the passing of the Voting Rights Act the crowning achievements of his political career. Five days after the act’s passage, the black Watts neighborhood in L.A. exploded. Thirty-four people died; hundreds more were injured; a thousand buildings damaged and destroyed. “Johnson was beside himself with grief,” Perlstein says.

The Watts backlash among white voters was brilliantly exploited by Nixon in the service of his political resurrection. After eight years as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon had lost the race for the presidency to John Kennedy and had run unsuccessfully for California governor in 1962. By the mid-1960s, Nixon was viewed as a noncontender.

“He spent the whole summer and fall of 1966 baiting Lyndon Johnson on Vietnam. LBJ would propose something; Nixon would propose the opposite,” Perlstein says. Finally Nixon got to Johnson, who lashed out at him at length at a news conference, thereby transforming “an obscure person into an important person.”

Perlstein gives Nixon his due as a brilliant tactician and a foreign-policy student with the long view. But he used his personal resentments to drive a wedge through America’s middle.

Nixon was “practically friendless as a youth,” Perlstein says, “from a family that always thought they were better than the world would let them be. He saw other kids reaping rewards that were justly his.”

In college, Nixon tried to join an “in” group called the Franklins; he wasn’t cool enough.

“That formed a template for his career,” says Perlstein. “It turns out there are a lot more uncool people than cool people.” Nixon became the defender of the square, the unhip, the uncool — the “Silent Majority”.

One instructive aspect of Nixonland is the realization that key players in the `60s dramas are still alive, well and influencing the debate today. Seymour Hersh, the groundbreaking New Yorker investigative reporter, worked as Eugene McCarthy’s press secretary. William Safire, who ghostwrote Spiro Agnew’s fiery anti-left, anti-press rhetoric, now writes genteel columns on language for The New York Times. Roger Ailes, one of Nixon’s first media-spin experts, went on to found the right-tilting Fox News.

But are our politics still driven by an era that’s now four decades gone? Many commentators on Nixonland have disputed that, pointing as evidence to the increasingly likely Democratic nomination of an African-American man for president.

Unexpectedly, the loquacious Perlstein ducks the question of whether Barack Obama’s campaign has healed America’s divisions — or merely glossed them over. Instead, he pointed this reviewer to a Washington Post op-ed he wrote earlier this year, where he noted how race and class issues have already defined this year’s Democratic campaign — Obama’s problems with the Rev. Jeremiah Wright; Hillary Rodham Clinton’s hardball pitch to white working-class voters.

“A President Obama could no more magically transcend America’s `60s-born divisions than McCarthy, Kennedy, Nixon or McGovern could,” Perlstein wrote. “Over the meaning of `family,’ on sexual morality, on questions of race and gender and war and peace and order and disorder and North and South and a dozen other areas, we remain divided.”