The month of August has always been good to the Ritchie Family. It was during August 1975, 1976, and 1977 that the trio scored three number one disco hits, fueling the most commercially successful period in the group’s history. Perhaps it’s because the Ritchie Family’s music captured the carefree spirit of summer, a time of blazing sunsets and whispering surf, of joyous, all-night dancing. Even the titles of their number one dance hits — “Brazil” (1975), “The Best Disco in Town” (1976), “Quiet Village” (1977) — were passports to adventures in paradise. While original group members Cassandra Wooten, Cheryl Mason-Dorman, and Gwendolyn Wesley emerged as regal songbirds who made the Ritchie Family synonymous with class and glamour, it was only a matter of time before they portrayed actual royalty. In this exclusive interview with PopMatters, the trio shares the story behind their celebrated disco classic, African Queens (Marlin/TK, 1977).

Named after arranger/producer Richie Rome, the Ritchie Family was masterminded by French producer

Jacques Morali via Can’t Stop Productions. Largely influenced by Rome, whose lush arrangements fashioned hit productions for the Three Degrees and Jackie Moore, Brazil (1975) featured the cream of Philadelphia-based Sigma Sound Studio session players. Barbara Ingram, Carla Benson, and Evette Benton (aka “the Sweethearts of Sigma”) sang vocals on the title track and helped send “Brazil” to the disco singles chart. From August through September 1975, the Ritchie Family’s cover of Ary Barroso’s bewitching standard completed a seven-week stint at number one.

Building on the success of “Brazil”, Morali decided to make the Ritchie Family more than a faceless, one-off studio project. He hired three vocalists who could morph his musical ideas into a legitimate recording and touring act. Two of the singers, Wooten and Wesley (at the time, Gwendolyn Oliver), had sung together since they were 11-years-old and subsequently enjoyed success as members of the local Philadelphia quartet, Honey & the Bees. “We lived in the same neighborhood,” Wooten explains. “We were best friends. Everything she thought was funny, I thought was funny. Everything that she hated, I hated. We were in lockstep.”

The third singer, Cheryl Mason-Dorman (formerly Cheryl Mason-Jacks), originally hailed from Columbus, Ohio. “When Cheryl came along, it was a little hard for her because her whole outlook was different,” says Wooten. “Gwendolyn and I were from the ‘hood so to speak. Cheryl already had a Masters degree. She was very down-to-earth, very friendly, and very sweet. It was fun and it was funny, but we all came together very quickly.”

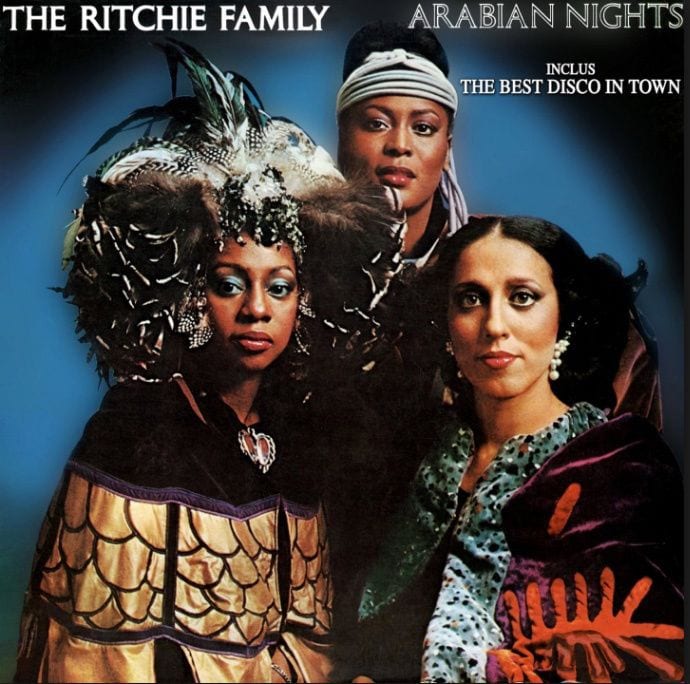

Arabian Nights (1976) unveiled the newly invigorated Ritchie Family. Once again, Morali recorded the tracks at Sigma Sound, but shifted the group’s US label home from 20th Century Records to Marlin Records, a subsidiary of Henry Stone’s T.K. Productions. He also added Phil Hurtt to the group’s creative team. Hurtt arrived with a number of illustrious credits to his name. He’d produced acts like Sister Sledge, Jackie Moore, Bunny Sigler, and the Persuaders, and penned tunes for the O’Jays, Billy Paul, and Joe Simon. Most notably, he collaborated with producer Thom Bell on the Spinners’ million-selling “I’ll Be Around”.

Upon recommendations from Richie Rome and Sigma Sound GM Harry Chipetz, Hurtt met with Morali and his partner at Can’t Stop Productions, Henri Belolo. Hurtt recalls, “The very first thing we did was ‘The Best Disco in Town’. Jacques gave me tracks that were recorded by some friends of mine — I didn’t know it was them at the time — Gypsy Lane. I took the tracks home after Jacques gave me what he thought was the melody for this whole thing. To make up the tune, I had to pull together all these little pieces that he had. I brought two sets of lyrics back for him to listen to. I sang the first set. He loved it so he never heard the second set!”

With lyrics by Hurtt, “The Best Disco in Town” was a clever compendium of various disco flavors, from Philly soul (“TSOP”) to Eurodisco (“Fly Robin Fly”), to hits by Labelle (“Lady Marmalade”), Donna Summer (“Love to Love You Baby”), and a sly nod to the Ritchie Family’s own “Brazil” and “Romantic Love”. “We were performing a little of everybody,” notes Mason-Dorman. “It was like you were going to a disco. You were standing outside and you opened the door and you heard this music being played. You closed the door. You opened the door again and somebody else is playing.” Grouped with original songs “Baby, I’m On Fire” and “Romantic Love”, Morali gave “The Best Disco in Town” the opening slot on Arabian Nights.

Side Two featured a side-long medley centered around the theme of the title track. The trio recorded their vocals in keys that were already set, a process that was dramatically different from what Wooten and Wesley had experienced in Honey & the Bees. “We were used to someone writing a song,” begins Wesley. “We’d listen to it with our manager. We’d figure if we liked the song and then we rehearsed it in our key. They’d go in and lay down the rhythm tracks. We’d come in and record and then they’d go back and put in the strings or horns. Jacques’ way of doing things was unique. He had a concept and then he would go in and record the whole track. The only thing that was needed was our voices. We had no say-so about it because it was really his thing. Of course being professionals, we did what we needed to do whether we liked it or not.”

Morali’s process worked: Arabian Nights was one of the hottest disco sets of 1976 while “The Best Disco in Town” became a worldwide smash. In August 1976, the song topped the national disco chart and ascended the Top 20 on both the pop and R&B singles charts. It also made the Top Five in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Australia, soared to number ten in the UK, and climbed the Top 20 in Germany and Sweden.

“It was phenomenal,” Wooten exclaims. “Coming from Philadelphia, you hope for a national hit. The international success of ‘The Best Disco in Town’ blew our minds. We had no idea that when we’d go to Australia, South America, France, Belgium, that they’d know all our music. That was one of the most remarkable things that we’d ever experienced! They’d collected pictures and newspaper articles. I remember in the Philippines, they gave us this huge book full of all this stuff they’d collected about the group.” Wesley continues, “I cannot remember one time that we weren’t treated royally. They absolutely adored us. They were extremely nice to us. I have nothing but great memories about that.”

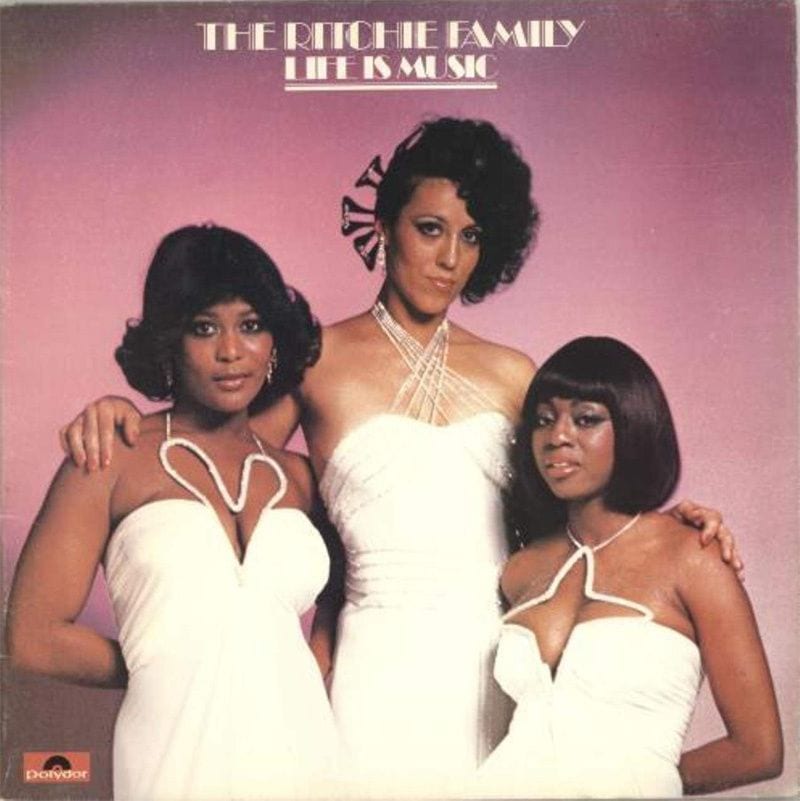

The Ritchie Family quickly returned with Life is Music (1977), an album that further honed the group’s identity while highlighting the respective talents of each vocalist. Hurtt was granted more time to work closely with the group on vocal arrangements. Having co-produced Honey & the Bees with Bunny Sigler, he had a very keen sense about what qualities each vocalist brought to the group. “Their voices are similar and yet they’re different,” he says. “Gwendolyn has a sweet tone to her voice and her demeanor is the same way — very sweet — but underneath all that is some fire. Wooten is a more earthy singer. She’s a very soulful singer. Cheryl’s voice probably embodies the two qualities that the other girls have, but her voice is a little bit stronger. When you put those three together, they have a really good blend, harmonically, and a good blend in their chemistry.”

Wooten continues, “We usually got with Phil and he’d play the music for us. We’d work out the harmonies. From the time that we got in, whether it was six hours, more or less, we got the job done in that allotted time. It would be in one session, generally. We didn’t do seven or eight hours and have to come back the next day to do it some more.”

Occasionally, Morali interrupted the proceedings with his own set of demands. “If the group was not smiling, Jacques did not think they were performing,” Hurtt chuckles. “He’d tell them, ‘Do it again. You are not smiling.’ I’m looking at him like, ‘What are you talking about? They sound great!’ I would tell the engineer, ‘Keep that track. Don’t erase that!'” Morali’s idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, Life is Music featured an appealing set of six tracks molded in a distinctive pop-disco style with traces of Philly soul.

However, the album marked Rome’s swan song with the group. “Richie Rome quit,” says Hurtt. “I felt bad about it because Richie was the one who put the whole thing together, musically, for Jacques in the beginning.” The group itself was left with more questions than answers about Rome’s departure. “At the time, we didn’t really understand what the issues were,” says Wooten. “We weren’t privy to the details and the parameters of what that relationship between Jacques and Henri and Richie was, but we were prepared to continue moving.” Legendary arranger Horace Ott replaced Rome and wrote arrangements for the group’s subsequent albums.

Within months of Life Is Music, Morali hatched African Queens, the fourth Ritchie Family album and arguably the group’s most ambitious set. “Jacques had his concept for Nefertiti, Cleopatra, and the Queen of Sheba,” Hurtt recalls. “It was the first time that I’d seen a producer like Jacques reach out to the African concept using three African queens. I think he had a respect for all women, but in this particular instance, African women.”

The trio welcomed the idea. “I thought it was a great idea because nobody ever illustrated it in that way,” says Wesley. “I thought it was about time. I really enjoyed that idea.” Mason-Dorman continues, “Since all of us are African American, it was fabulous to be able to portray three of the most famous African queens who existed. We were excited about it and I think he picked the right ones for each of us. Cassandra had that flair that you would expect from the Queen of Sheba and Gwendolyn had that regal Cleopatra look. I kind of looked like Nefertiti when I put on her outfit. I did some research about my queen and I knew the things she stood for, which were similar to some of the things that I stood for.”

Writing the lyrics, Hurtt fleshed out a narrative for each of the queens and created an overarching theme: “three different shades of love who gave the world a shove”. He was inspired by what each queen represented plus the strong personas within the Ritchie Family. The lyrics also had to complement Morali’s flamboyant production style. “I was listening to the music and understanding that it couldn’t be serious,” says Hurtt. “It had to be campy. It had to be fun. That’s the way I had to approach it, unlike a lot of the R&B and pop things that I’ve done. It was more pop-disco than it was soulful, but it still worked.”

Morali still sought to relay some sense of authenticity and hired one of the most revered percussionists in the world. “I walked into the studio and I saw this drum section with these huge drums,” Hurtt continues. “I saw Olatunji with the people that were attending to him. They called him ‘Baba’. It was exciting for us. I think that Jacques thought adding authentic African drums would make it grittier.” Nearly 13-minutes long, “African Queens” was made of many elements: anthemic melodies, romantic flourishes, and dramatic musical interludes. Like a short Hollywood film set to a 4/4 beat, it introduced three characters whose stories left indelible impressions on listeners.

Side Two was bookended by two collaborations between Morali, Belolo, and Hurtt, “Summer Dance” and “Voodoo”. Both songs gave the group some solo turns. “We wanted the people to know we sing,” says Wooten. “One of the things that we wanted to do more of was sing songs that had lead vocals and backgrounds. There was a little more of that with ‘Summer Dance’ and ‘Voodoo’. I felt like we were being heard at last.”

The trio’s vocals wafted above an incessant beat and intricately orchestrated strings. Both songs typified Morali’s way of working, which meant sparing no expense on the production. “He hired the best people he could find in the city,” says Hurtt. “He knew who to cast. He would sit with Gypsy Lane and say, ‘Give me a groove.’ Gypsy Lane would find the groove and Jacques would do his interpretation of a melody, what he wanted to hear. By the time he got the tracks laid, then it was time to have somebody like myself come in, take his idea of a song, and write the song. I would give him a set of lyrics and make sure that the singers knew what I was doing. He would ask me to go in and work with them in the studio.”

Rounding out a trio of songs thematically linked by warm climates, Morali brought Les Baxter’s “Quiet Village” onto the project. Eighteen years after Martin Denny scored a Top Ten hit with the song, Morali brilliantly recast it for clubs. The group was only required to learn four separate lines of lyrics. “There was so much music,” says Wooten. “I knew that it would be a difficult song to do live because when you have that much music you’re sashaying around on the stage for long periods of time. How do you keep the audience engaged? I guess I thought about that more after it was done. When I listen to it, it’s beautiful music. I loved the music. You were transported.”

Just looking at the African Queens album was enough to transport listeners, even before the needle dropped on the record. All three members were adorned with custom gowns designed by Eve’s Costume in New York. “They had done the costumes for Roots (1977),” notes Wooten. “We went there and we were just fascinated by the fabrics. There were people from Broadway shows that we recognized who were there for fittings. That was just an amazing experience. Those costumes were heavy! I had this big headdress on and a huge jewel-like collar.”

Scaled-down versions of the outfits doubled as stage wear. “The costumes were gorgeous,” Mason-Dorman continues. “They were made for us, that’s why they fit us so well. Because we were traveling, we couldn’t wear those all the time, so we had another one made for regular shows. The gowns were less elaborate and less heavy so we could pack them and carry them around.” Whether gracing the set of American Bandstand or charming television audiences in France and Italy, the group promoted African Queens in full regalia.

Choreographer Richard Moten blocked movements that accentuated the flow of the trio’s gowns. He’d known Wesley and Wooten even before the Ritchie Family. “When Cassandra and I were in the Honey & the Bees, we took dance lessons,” says Wesley. “Richard was our dance instructor. When we got with Jacques, and after things started rolling, he wanted to know if we knew anyone who could choreograph our pieces. We asked if Richard wanted to do it and he said he did. That’s how he got the job.” Moten occasionally accompanied the group onstage during dance sequences. He’d later work with Village People and create the iconic moves to “Y.M.C.A.”.

By August 1977, “Quiet Village”, “African Queens”, and “Summer Dance” collectively held the number one spot on the disco chart for three weeks. The popularity of Morali’s style continued to dominate the chart when his production of Village People’s self-titled Casablanca debut supplanted the Ritchie Family from the top for seven weeks. However, African Queens struggled on the albums chart, stalling at #164 on the Billboard 200 and peaking at #57 R&B.

Though T.K. Productions was one of the most prolific disco-oriented labels, the company’s success with the Ritchie Family in the pop and R&B arenas had dimmed somewhat since Arabian Nights. Perhaps it’s because the Ritchie Family had less direct contact with the label than other artists on the roster. “We didn’t really go to the record company and hang out or mix in and blend in,” says Wooten. “I don’t remember meeting (T.K. founder) Henry Stone. Most of our interactions were with the people in New York at Can’t Stop Productions. We had people out of Florida that ended up going on the road and working with us. We worked with (T.K. artists) KC & the Sunshine Band, Dorothy Moore, and George McCrae.”

Of course, the US represented only one market. Internationally, the Ritchie Family stood among the world’s top disco acts. “Jacques and Henri came with a global perspective about where they wanted us to be,” notes Mason-Dorman. “We are very grateful to them for that. We got to see the world when we were young. We got to enjoy a lifestyle that opened up our vista about what life could be about and what performing could be about.”

However, recording three consecutive albums with Morali exacted a toll on the group. “It was work on our part just to have a relationship with him because he was very demanding,” says Wesley. “He didn’t mean to, but he tried to dictate our lives. There were times when, if we were going to have an interview, he would tell me, ‘Gwendolyn, you talk!’ It’s like, ‘No, we’re a group. We’re going to all talk.’ He would try to single somebody out, like Diana Ross & the Supremes. We weren’t going to do that. There was just so much that I could take.”

Wooten adds, “It just got to be a contentious thing. After getting over the initial excitement, we realized that, creatively, we weren’t going to have a lot of input. We felt like glorified robots. Jacques felt like, ‘Look at how much I’m doing for you. You had nothing until you met me.’ We felt that his ideas weren’t the only ones in town. We had ideas. We still have ideas.”

To the trio’s shock, they were dismissed from their own group. “One day we were there and the next day we weren’t,” says Mason-Dorman. “There were some other people there that were being called the Ritchie Family.” Hurtt was equally surprised by the switch. “I didn’t know what had happened,” he says. “When I went to the studio for the sessions that followed that, there were three new girls in front of me. Where’d they come from?” The founding members of the Ritchie Family had no forewarning that Ednah Holt, Jacqui Smith-Lee, and Theodosia Draher would soon replace them and resume recording with Morali.

“I did not realize until much later that what Jacques had actually planned to do was not renew our contract,” Wooten confides. “He was probably already out there shopping for other girls. We didn’t know that. It was hurtful and it was insulting. I felt like my career had been aborted. We did not have a chance to fulfill what we wanted to do because of somebody else’s ability to cut us off. We didn’t own the name so we couldn’t do anything with the name.”

While Wesley retreated from performing, Wooten and Mason-Dorman tried to salvage their singing careers. They formed CasMiJac with Michelle Simpson and sang background on John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Double Fantasy (1980). Following Lennon’s murder, both Mason-Dorman and Wooten stepped away from singing, seldom disclosing their past to others. “I convinced myself that I didn’t want to sing anymore and that was just a phase of my life,” says Wooten. “That wasn’t true. It was that I suppressed my true feelings. I adjusted and I went on. I was happy, but deep in my heart I never got a job that I enjoyed more.”

Decades passed before the original Ritchie Family members realized that listeners had not forgotten about them, especially when Ritchie Family archivist, Hans de Vries, contacted Wooten from the Netherlands. Mason-Dorman recalls, “Hans contacted Cassandra and said, ‘I’m looking for Cassandra Wooten of the Ritchie Family. Are you her?’ She wrote back, ‘Yes, I am.’ We had no idea that anybody anywhere remembered us. We thought that nobody cared what happened to us, because we never got totell anybody what happened to us. We just thought that time in our lives was over.”

With the advent of social media, Wooten and Mason-Dorman realized just how much they were still adored around the world. In 2011, after trademarking the group’s name, they relaunched the Ritchie Family with new member Renée Guillory-Wearing. Since reuniting, they’ve been booked at first-class casinos in the US, made promo appearances in New York for the book First Ladies of Disco (James Arena, 2013), performed at the prestigious DuPont Theatre in Wilmington, Delaware for the 2013 Golden Mic Awards, and recently co-headlined the 2018 Disco Diva Festival in Gabicce Mare, Italy. Most impressive of all, their voices graced the Billboard dance charts for the first time in nearly 40 years when their comeback song “Ice” (2016) peaked at #40 in November 2016.

In reclaiming their legacy, the Ritchie Family seeks to maintain the glamorous, sophisticated image they projected in the ’70s. “If you’re the Ritchie Family and this image of yourself is a classy disco group, then you come out and give people that,” says Wooten. “You don’t come out and give the people a watered-down, cheapened version. One thing that you can say about Jacques and Henri, they wanted to do everything first class. They took us to the best places, whether it was restaurants or clubs. They always used the very best musicians and the best studios. The guys who took photographs for Vogue and high fashion magazines, these were the people who took our photos for our album covers. It wasn’t just Joe up the block! They never skimped. They were willing to spend the money. They set a certain standard and it’s a standard that we’ve come to expect.”

Reflecting on African Queens, the group appreciates their decades-long friendship with Phil Hurtt. “He’s a great songwriter,” says Mason-Dorman. “He was a good teacher of music. He was there to hear how we sounded, so he could apply that knowledge to whatever he was writing for us. He’s so personable. He was fun to work with.” Wooten concurs, adding, “Phil was just a delight, very warm and bubbly, always encouraging and very supportive. When we did something well, he’d be our cheerleader: ‘Yes, yes! That’s that sound.’ He was just a cool guy.”

Hurtt has equal affection and admiration for the group. “I really enjoyed working with them because we had a really great time,” he says.” African Queens was a culmination of a relationship with some great women and the time that we spent together. They were receptive to the ideas that I would give them vocally. They listened. They worked hard. All of them were comedians. We laughed the whole time. We had a great run together. Hopefully, we can do more.” African Queens not only remains a highlight of Hurtt’s history with the Ritchie Family, but part of the gateway for a whole new legion of fans discovering the group’s legacy.

Among the albums the trio recorded in the mid-’70s, African Queens also holds a special place for the original members of the Ritchie Family, if only because it was their last album with Morali. “The albums are all so different in their own way, but when I listen to African Queens, there’s a little sadness,” says Wooten. “It’s different when you’re doing something for the last time and you know it, but it was the last album that we did and we didn’t know it. It was the end of an era. We’re very proud of African Queens because ‘three different shades of love’ was us. Each of us was very satisfied with the historical person that we were matched to be. We were very happy with that whole concept.”

As much as Cheryl Mason-Dorman, Cassandra Wooten, and Gwendolyn Wesley are music icons to audiences across the globe, they are also survivors. “We remained who we were before we went in,” Wesley says. “We didn’t have any drama at all. We still have a very good relationship.” That sentiment is shared among all three original members. “All along we were building a family,” Mason-Dorman concludes. “They called us the Ritchie Family. We weren’t really family in terms of blood, but webecame a family.” Indeed, the bond between these three regal queens lives beyond the grooves.

- The Ritchie Family | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links | AllMusic

- The Ritchie Family - Brazil 1975 - YouTube

- The Ritchie Family - The Tribute Page - Home | Facebook

- The Ritchie Family Discography at Discogs

- The Ritchie Family - Wikipedia

- Ritchie Family - The Best Disco in Town 1976 - YouTube

- The Ritchie Family - Wikipedia