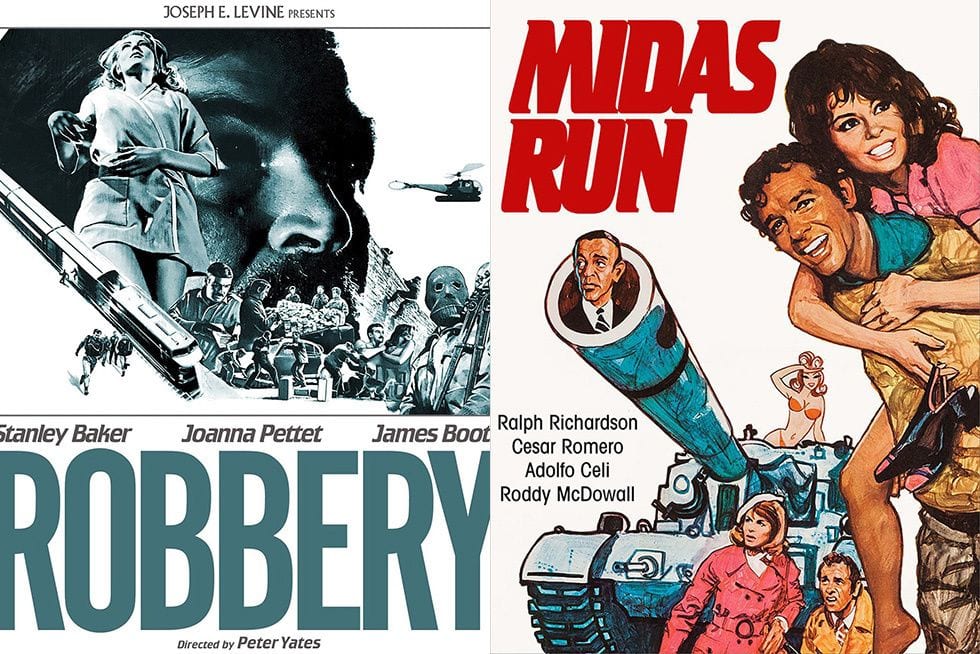

The heist thriller or caper movie achieved its glamorous apotheosis in the 1960s, and we can speculate on reasons why in a moment. Many minor examples have escaped attention, often because they just haven’t been widely available on home video or haven’t been presented to best advantage. Kino Lorber corrects that condition for two Blu-rays arriving at the same time: Peter Yates’ Robbery (1967) and Alf Kjellin’s Midas Run (1969).

A Few Preliminaries

In the postwar evolution of this subgenre, Hollywood films focused on petty, sweaty, lower-class underworld figures whose meticulous heist plans were undone by their own unscrupulous cross-purposes and bad luck. John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950), in which you can witness Hollywood cinema becoming modern before your eyes, provided the template that led to Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), Stanley Kubrick‘s The Killing (1956) and others, including a Missouri-shot indie called The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery (Charles Guggenheim, John Stix, 1959) starring little-known up-and-comer Steve McQueen. Keep him in mind.

At this time, Hollywood films paid obeisance to the heavy hand of the Production Code, which forbade allowing crime to pay or criminals to escape unpunished. In fact, movie morality was such that even countries far from Hollywood obeyed this rule, and you can find heists in a cropper of films made in England, France, Italy, and elsewhere. Everyone was sensitive about giving the public larcenous ideas. Audiences could savor the escapism of being in on planning a heist, but the plans had to go awry before they were allowed back out into the streets.

In France, Jean-Pierre Melville felt inspired by the American model to create heists with working-class criminals, as in Bob le Flambeur ( Jean Pierre Melville, 1955), while Mario Monicelli pioneered “comedy Italian style” with the sad sacks of Big Deal on Madonna Street (Mario Monicelli, 1958). Meanwhile, displaced American director Jules Dassin escaped the blacklist by coming to Europe, where he shot two seminal capers in a more glamorous mode: Rififi (1955) and Topkapi (1964), both of which emphasized the heist itself as a major showpiece, kind of like a musical number only scored with a held breath.

Cinema of the ’60s entered a chic phase whereby even well-heeled, high-living, champagne-swilling types were planning bank heists and museum capers and jewel robberies and such anti-social romps, partly in throwback to early ’30s pre-Code antics about swanky European jewel thieves and partly because Alfred Hitchcock made To Catch a Thief (1955).

At the same time, affected by the sadism and decadence of the James Bond films, even the newly high-tech WWII adventures began to resemble capers, e.g., J. Lee Thompson’s The Guns of Navarone (1961); Michael Anderson’s Operation Crossbow (1965); Brian G. Hutton’s Where Eagles Dare (1968); Robert Aldrich’s sour, angry, Vietnam-conscious The Dirty Dozen (1967); and the movie that made a literal breakout star of McQueen, John Sturges’ The Great Escape (1963). That’s a prison-escape movie, which film historian Nick Pinkerton, on the commentary to Robbery, calls a special form of heist movie that inverts the typical “break-in” scenario.

The crucial difference with the WWII adventures is that audiences definitely want the heist to succeed; it’s even crucial that it does, since the authorities are clearly defined bad guys. Thus do these movies cleverly channel the genre’s anti-authoritarian impulse into a justified and heroic getaway.

Concomitant with such patriotic alibis, the ’60s heist film evolved to where it was no longer a foregone conclusion that the heist would be bungled and nobody would get away with it. This was a sign of the era’s relaxation of moral imperatives. The Hollywood Production Code was weakening as civilization seemed to be entering a period of decadence and decline marked by rebellious youth, short skirts, sexual permissiveness, Cold War cynicism, colonial wars, and general political uppity-ness that kept shocking the bourgeois.

These social and narrative elements combined to introduce tension and surprise into the heist genre, as ticket-buyers could no longer be certain of the outcome. Maybe the anti-heroes really would end up swilling more champagne — like McQueen (you knew it was coming) in Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). That’s one of several capers during this era in which one or more conspirators got away with the loot, and this gradually edged more toward the norm than the exception. Peter Collinson’s The Italian Job (1969) literally balances on the edge between these opposite impulses.

Another ingenious way to co-opt the anti-authoritarian impulse of heist capers was to contain their heists within the goals of the state’s law and order, and this was the hybrid that flourished on TV with crime-fighting criminals on The Rogues (1964-65), It Takes a Thief (1968-70) and even Mission: ImpossibleMission: Impossible (1966-73), whose heroes are nothing if not flim-flam artists pulling off gigantic swindles and heists for Uncle Sam, and on the taxpayers’ deniable budget. (As Tom Cruise’s recent career shows, that concept has legs.)

It was into this heady cultural stew that Robbery and Midas Run arrived.

Robbery, Dir. Peter Yates (1967)

The British Robbery is based directly, with creative license, on a famous 1963 event trumpeted in the British press as the Great Train Robbery. After a three-day bank holiday, a well-organized gang of thieves hijacked the equivalent of a few million dollars from a Royal Mail train. Most of them were apprehended quickly, but some got away for a longer duration.

As based on Peta Fordham’s non-fiction book The Robber’s Tale (1965) and scripted by director Yates along with Edward Boyd and George Markstein, this film falls into the working-class mode of the heist genre. Although it’s true that the brains behind the scheme, Paul Clifton, has a more upper-class lifestyle, it’s also true that he’s played by Stanley Baker, who became a star in British cinema with a working-class persona, such that we get the feeling that Paul clawed his way up to the comfortable lifestyle that still doesn’t quite satisfy him. His trophy wife (second-billed Joanna Pettet) has little to do but drink and brood while he spends hours planning his next job.

This is a movie of masculine tension, comradeship and rivalry, whether among the many criminals recruited into the job, or among the railway workers who find themselves beaten or tied up, or among the police who try to put the pieces together, as embodied by Inspector Langdon (James Booth). The script’s structure links a series of setpieces, including a prison breakout, with atmospheric digressions that aren’t necessarily relevant to the story, although it’s difficult to be certain as the story never quite reveals where it’s going until it’s already there. Thus, viewers are intrigued and pulled along in a story that feels both “cubist” and sleek, sometimes wandering freely and taking a breather and sometimes barreling like the mail train.

Arguably, the most important setpiece isn’t the actual robbery, though that’s certainly handled with both criminal and cinematic efficiency. The real eye-catcher is what occurs in the first 20 minutes before Baker ever shows up on the screen. For reasons that eventually become clear but are not spelled out in advance, we’re dropped into the middle of some breathless hijack amid London traffic. Just as we think the miscreants are getting away with their loot, they’re spotted by police and we’re plunged into an edge-of-the-seat high-speed car chase through the city, all squealing tires and hand-held commotion and brushes past alarmed pedestrians. (See also Bill Gibron’s The 10 Best Car Chase Films, PopMatters, 2 Apr 2015).

That brings us to why this lesser-known film is more significant than its relative obscurity suggests. If this lengthy chase reminds viewers of the following year’s Bullitt, it’s because Steve McQueen (him again!) saw this movie, with Yates making maximum use of the real London streets, and decided Yates should direct McQueen’s upcoming San Francisco procedural, whose show-stopping car chase spawned a thousand imitations. Thus, the modest Robbery became Yates’ pass to a very reasonable Hollywood career, including Oscar nods for Breaking Away (1979) and The Dresser (1983).

Throughout the film, real locations are preferred to sets, and those locations are exploited with verve and an excellent compositional eye, which is why this film becomes such a time capsule. Yates benefits immeasurably from working closely with two of the most significant craftsmen in British cinema, editor Reginald Beck and photographer Douglas Slocombe, and their unfussy but effective work here is a consistent pleasure to observe.

The latter’s glittering career included two of Charles Crichton’s Ealing comedies, the heist film The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and the train film The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953), so he knew heists and trains. Although this gritty near-docudrama isn’t a color-saturated film, the reds pop (the train, the signals, the booths) and the many night scenes boast admirable clarity that comes through on this 2K scan. Slocombe’s later works include the aforementioned The Italian Job, which, like Robbery, was produced by Stanley Baker and Michael Deeley, and the first three Indiana Jones films.

Frank Finlay plays the most reluctant member of the gang, while Barry Foster, George Sewell, William Marlowe and Clinton Greyn play the main confederates. Pinkerton’s commentary discusses the careers of everyone involved, giving context on the real-life robbery and making connections with other Yates films, most notably the working-class criminality of The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973). He also draws a link between heist films and “putting on a show”, with the mastermind as the director who rehearses everyone diligently for the curtain-raising.

Midas Run, Dir. Alf Kjellin (1969)

If Robbery is the serious, working-class, nail-biting heist, Midas Run is the light, larkish, glamorous heist, almost brazenly announcing itself as trivial escapism. The opening credits bear a vague similarity to those of Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1953) in that the camera keeps focusing on the feet of its subject. Since that subject is Fred Astaire, the film is correctly showing off his elegant assets as he walks down the London streets in black tails and top hat, and his jaunty step fools us into thinking he’s about to break into a bit of tap.

Astaire plays Mr. Pedley, supposedly English but with an American mother, which may explain the lack of English accent. He works for MI-5, and another year has gone by without his being recognized in the annual Honours List for knighthoods. As he’s on the verge of retirement and being replaced by the pompous young Wister (Roddy McDowall), Pedley concocts the hijack of a gold shipment. It’s not unlike the previous film’s robbery, but this one involves liberating the bricks from a small chartered airplane, which means it must be forced down in mid-flight.

Pedley recruits an American academic, Mike Warden (Richard Crenna), an amateur military strategist recently fired for participating in student demonstrations. While depictions of such demonstrations in this era’s pop culture are usually vague window dressing about nothing in particular, this one does have an anti-LBJ sign with a popular phrase: “Hey hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

Even so, this film is much more concerned with WWII politics than the contemporary stripe, for the people recruited for the job include a former Fascist Italian (Adolfo Celi) and an ex-Nazi pilot (Karl-Otto Alberty). Also highly visible is the striking Carolyn De Fonseca, a prominent dubbing artist who, ironically, keeps a tight lip here. Pedley’s fuddy-duddy Foreign Office boss (Ralph Richardson) is similarly obsessed with the good old days of the war. Everyone seems to be looking backward.

Apropos of nothing besides good shooting locales for cinematographer Kenneth Higgins to capture, Pedley manipulates Mike into coming to Venice to be pitched on the idea of the hijack. There Mike meets and falls for Sylvia (Anne Heywood), who’s in the act of leaving her gormless husband because he expects her to have opportunist sex with a decadent Italian aristocrat (Cesar Romero, well cast) who tosses money into a fountain and surrounds himself with pretty young things of flexible sexual orientation in the movie’s most “shocking” and “mod” scene.

Heywood, a former beauty contest winner with an aura like a softer Glenda Jackson, habitually made films with her husband, producer Raymond Stross, and this is their light-hearted entry in between two sexually edgy items, the lesbian/bisexual triangle of The Fox (Mark Rydell, 1967) and the sex-change drama I Want What I Want (John Dexter, 1972). In Midas Run, Heywood even gets to a sing a James Bond-esque title song, very prettily, with lyrics by Bond-master Don Black and music by Elmer Bernstein of The Great Escape.

As film historians Emma Westwood and Lee Gambin observe on the commentary track, Midas Run very much centralizes Heywood’s role, especially at the end, and continually presents her in a glamorous light. These choices include what feels like an intrusively “arty”, very of-its-era sex scene full of superimposed nature shots and rapidly edited soft-focus close-ups. For that scene, the film is like The Thomas Crown Affair crossed with Bo Widerberg’s Elvira Madigan (1967).

Stross made this film for Selig J. Seligman’s Selmur Productions. Seligman, who’d been a U.S. Army lawyer at the Nuremberg war trials, worked his way into TV production with a short-lived drama series of legal re-enactments, Accused (1958-59), before finding success with WWII series Combat! (1962-67) and Garrison’s Gorillas (1967-68). Then he branched out into a series of features produced in England (virtually all now issued by Kino Lorber), of which this is the final example. His previous film was another heist movie, Diamonds for Breakfast (1968).

If Robbery sometimes digressed for the sake of atmosphere, Midas Run is almost all breezy wool-gathering that eventually gets around to the big job and its aftermath, whereupon a narrative twist we can’t specify turns the story from one kind of heist into a different type, mentioned above. This is when Sylvia becomes most important to the story, while Mike is at sixes and sevens and Pedley continues his behind-the-scenes masterminding for his own purposes.

Hardy British character players John Le Mesurier and Maurice Denham provide trimmings, and Astaire’s son Fred Jr. can be glimpsed as the co-pilot.

The script is credited to James D. Buchanan, Ronald Austin and Berne Giler. Buchanan and Austin were TV writing partners who probably got this gig on the strength of the 1966-67 series T.H.E. Cat (about a cat burglar turned hero), which also led to work on Mission: Impossible. They’d later write Harry in Your Pocket (1972) and the TV movie Hijack! (1973), so their work feels all related.

Similarly, TV director Alf Kjellin seems likely to have gotten this gig thanks to his spy shows I Spy, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Mission: Impossible. Kjellin, who began as an actor in Sweden, stuck with American TV. There’s some indication that his strength lay in horror, as in the TV movie The Deadly Dream (1971) and episodes of The Sixth Sense (1972) and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1962-65). The latter series includes his celebrated episode “Where the Woodbine Twineth”, about a girl doll that comes to life. In contrast to these works of more personal engagement, Midas Run does have an air of work-for-hire. It’s highly professional, yet not quite as quick and sparkly as it means to be.

As with so many films of its time, what appeals to us most is the time-capsule quality and the light it sheds on social attitudes as it plays with the tropes of a popular genre. Even minor films have something to tell us, and this one acknowledges political and social unrest between generations and among gender roles. The film’s most subtle aspect is what it says about the manipulations of the upper class for its own benefit, and how those in charge reward themselves or persist in sinister attitudes, so that criminality or indeed fascism become matters of degree.

Westwood and Gambin mention some of these issues as they spend their commentary playing off each other and naming the thousand other movies it reminds them of. As with Robbery, the image looks good and the only other meaningful extra is the trailer. This print opens with the original “M” rating (for Mature), now designated PG on the package.

- 'Now You See Me' Is but an Illusion of Substance - PopMatters

- A Little Ominous Noir Music Makes Jules Dassin's 'Rifif' Nearly ...

- Widows, Steve McQueen (film review) - PopMatters

- Let's Get the Good Stuff Out: An Interview With James Newton ...

- 'Jackie Brown': Is a Love Story, a Heist Film, an Offbeat Crime Story ...

- The Working Man's Heist in 'The Asphalt Jungle' - PopMatters

- Widows, Steve McQueen (film review) - PopMatters

- Truth and the Classic Heist Film: Director James Marsh on 'King of ...

- The 10 Best Car Chase Films - PopMatters