Late in American Witness, when photographer Robert Frank is on tour with the Rolling Stones (more on that in a bit), RJ Smith lays down the line that underlies the entire project: “Everybody was looking for the real.” In the many artistic circles he engaged, with the people he cherished and those he held at arm’s length, Frank is perpetually looking for the real, determined to capture it on photograph or film.

Frank has always been simultaneously an insider and an outsider, not only as an American but elsewhere in the world as well. Smith begins Frank’s story in Switzerland, prior to World War II, where his Jewish family has moved but was never accepted: Frank and his brother were granted citizenship the day after the war ended, but their father was not given that honor. Always restless in Switzerland, Frank settles in the United States but does not truly settle down. He photographs New York City perpetually, avidly pursuing connections, experiences, and paid work. Suddenly, he is off to South America, where he continues to photograph the landscapes and people he encounters. Back in New York, Frank develops a friendship with Edward Steichen and the photographers with whom he roams the city, shooting only with available light. He also develops a romantic relationship and marries his girlfriend, Mary Lockspeiser, who shortly thereafter gives birth to their son Pablo. Mary is also an artist, and together the young family lives a difficult life on the margins in several European cities, finally moving back to New York in 1953. Indeed, the frenetic pace of Frank’s life can be exhausting or exhilarating, depending upon the mood of the reader.

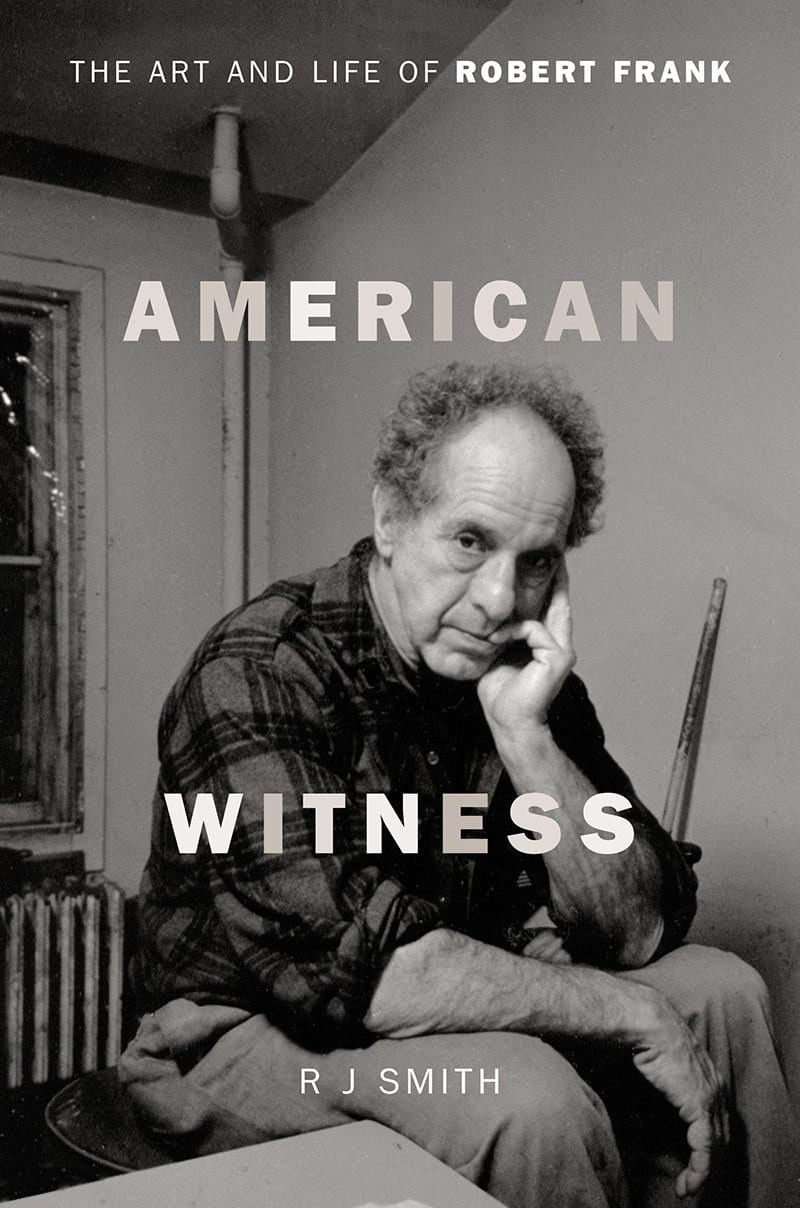

Smith notes in the introduction that Frank refused permission for any of his photographs to be included in the book. While this decision disappoints author and reader alike, Smith offers rich, descriptive language to capture the post World War II life in New York City that Frank photographed: “Nightclubs and fancy restaurants were moving to Fifth Avenue and points east. In their place were cavernous night-own cafeterias and pinball arcades and shops selling live turtles, pictures of girls in underwear, cigars, hamburgers, and Ouija boards.” Smith’s writing entices the reader on a quest for the absent images that seemingly should be stitched into the center of Smith’s book. The array of photos that are included in the book, while not by Frank himself, typically include him, along with other photographers, artists, and writers.

That Frank can be “difficult”: uncooperative, dismissive, or unfriendly, is laid out clearly in the introduction as Smith relates the stories of trying to get Frank to work with him in any manner in producing this book. Whether the taint of this difficulty is carried forward by the reader or the author is hard to tell, but it remains a struggle to find much warmth in Frank’s character. As Frank’s story evolves, Smith discloses his growing understanding of Frank’s temperament and how, for example, he sought to make himself inaccessible in an effort to create a more legendary artistic persona. Since Frank generally did not like people, Smith explains, this was not a difficult undertaking. Frank’s attitude does not diminish his brilliance. In fact, in the image of the tortured artist, it adds to the mystique of his genius, much as Frank himself intended.

The other characters who appear in Frank’s story win the audience’s enchantment, from his wife Mary to poet and activist Allen Ginsberg to photographer Walker Evans, with whom Robert Frank became acquainted in the ’50s. Evans recommended Frank for the Guggenheim fellowship that resulted in the book The Americans. Driving across the country, Frank shot and developed more than 27,000 exposures. He ultimately chose only 83 from among them. Published in 1958, the book captured a version of the United States that many Americans found confrontational and critical, not portraying the idyllic version of the nation they preferred to uphold. Over the past 60 years, The Americans has become an iconic collection of images that makes a holistic artistic statement about postwar United States. Although Frank invited Evans to write the book’s introduction, he replaced Evans with Jack Kerouac, adding another monumental voice to the book.

Frank was already a legendary presence when Mick Jagger chose him to shoot the cover of the Rolling Stones’ 1972 album, Exile on Main St. There was a powerful vibe between the photographer and the band, and Frank joined the Stones on the US tour to support the album. The resulting film, Cocksucker Blues, was far too intimate a glimpse into the road life of the Rolling Stones and was effectively suppressed by the band and their attorneys. Completed by Frank in 1977, the film did not see a theatrical release but has taken on the tantalizing allure of a censored work of art. When the film had a rare sold-out screening at New York’s Film Forum in 2016, Jim Farber wrote in The Guardian: “The cherished leer of Cocksucker Blues captures a quality the recent HBO series Vinyl pined for and missed entirely. […] With its shaky camera work, blurry image, and muddled sound, it feels more like the work of a peeping tom than a film-maker.”

One of the pleasures of Frank’s story is that he has inevitably found himself in engaged, passionate artistic circles. Initially with other photographers, then with the community of artists in the Bowery, later with young filmmakers like himself, Frank played a part in the development of the arts in the United States from midcentury on. American Witness anecdotally demonstrates Frank’s far reaching influence. Smith’s skills as a storyteller make this an engaging journey.