Legend has it that when Rudolph Valentino died of peritonitis at age 31 in 1926, it caused a wave of public hysteria and even suicides among his legion of mostly female fans. The funeral was literally a riot and a publicity spectacle, with at least one mourner, friend and fellow star Pola Negri, making a spectacle of herself and claiming to be engaged to him.

Valentino’s luster has never dimmed, as witness the fact that he’s one of the few silent movie stars whose name still means something to the masses. People who’ve never seen one of his films probably know of him as the “Latin Lover”, still an object of curiosity and speculation for his movies and for the scandals that erupted around him, which included an unconsummated first marriage and a bigamy charge.

That’s why Valentino is still marketable. To prove it, Flicker Alley offers two new releases as Blu-rays on demand, a BD-R format in the same way that on-demand DVDs are in DVD-R format. “Rudolph Valentino Collection, Volume 1” and “Rudolph Valentino Collection, Volume 2” mostly replicate the four features previously seen on the company’s 2006 box “The Valenino Collection”, now going for extortionate prices on Amazon. Owners of that set must hold onto it, for the bonus items haven’t been ported over. Instead, we get two new films.

Who was this Valentino? Raised in Italy as Rodolfo Guglielmi, the 18-year-old Valentino emigrated to New York in 1913 and eventually worked as a tango instructor and taxi dancer. This somehow led to a scandalous involvement with a Chilean heiress who shot her ex-husband, after which he started taking acting jobs and found himself in Los Angeles, trying to get parts in pictures while continuing his dancing.

June Mathis, a prime mover at Metro (later MGM), spotted his small role in Albert Parker’s Eyes of Youth (1919) and lobbied to cast the young unknown in their epic production of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), directed by Rex Ingram. Valentino’s stardom was launched and the persona of “the Latin Lover” suddenly became a thing in Hollywood, as his roles negotiated the foreign promise of smouldering sexuality (since only foreigners had sex) with the all-American, midwestern, WASP-ish promise of honorable maidenhood and two-fisted manhood.

The paradoxical packages packed ’em in, leading some offended he-men of the press to air veiled snifferies about Valentino’s sexuality that weren’t helped by his stormy marriage to Natacha Rambova and her friendship with another volatile exotic, Alla Nazimova. His untimely death provided his final lionization as one of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars and one of its most glamorous casualties.

Volume 1 opens with the picture that caught Mathis’ eye. Writer-director Albert Parker’s Eyes of Youth (1919) is a mystical drama conceived as vehicle for Clara Kimball Young, one of the most popular stars of the Teens. The third act features a brief but pivotal role for one Rudolfo Valentino as Clarence Morgan, “a cabaret parasite”.

Our story opens in the Himalayas with lots of title cards contrasting the East, source of wisdom and spirituality (the Three Wise Men are cited) to “the Western World, where the eyes of men have been blinded to the things of the spirit by the cruel struggle for gold.” A yogi’s disciple (Vincent Serrano), who will later be referred to as a Hindu in dialogue we’re not necessarily meant to take as accurate, is ready to go forth in the world, wearing a “fakir’s pack” because the West only tolerates such things when disguised as amusement.

Meanwhile, in the West, one black boy and one white boy try to tie a can to a little dog’s tail, only to discover he doesn’t have one. They’re interrupted by glamorous heiress Gina Asheville (Young), and the black boy sneers, “No dog with no tail ain’t got no rights.” Gina asks her aspiring engineer boyfriend Peter (Edmund Lowe), “Why must people be so cruel and cause such unhappiness!” Miles away, the disciple pricks up his ears, spiritually speaking: “The first far-off cry of a pure heart asking for guidance that he heard in months of wandering.”

A lot of busy exposition establishes that Gina has at least four suitors for her attention and lots of contingencies to consider. Everyone wants a piece of her. Her industrialist father (Sam Southern) wants to sell her off to an old financier (Ralph Lewis) to cover his debts and support her idle brother (Gareth Hughes) and sister (Pauline Starke). A young banker (Milton Sills) lectures her on duty and asks her to “wait for him”. An impresario (William Courtleigh) promises to make her an opera star, while the engineer boyfriend chafes in the wings. With a crystal ball, the disciple shows up at the party and offers Gina a chance to experience her next five years along three different paths: Duty, Ambition, or Wealth.

Duty finds her struggling as a teacher in a mixed-race classroom, reflecting the equality of the two boys in the early scene. Later, a spiffily dressed black man will be seen employed as the telephone operator in a hotel, something I’ve never noticed in any other film of the era, so this picture was making some effort at progressive casting in its images, though it will save its most explicit lectures for sex roles.

The Ambition timeline involves a divorce scandal that curiously reflects Kimball’s real-life notoriety; the year this film came out is when her husband was granted a divorce. In the Wealth part, she gets mixed up with the cabaret parasite, leading to another divorce scandal. This one’s a frame-up, leading her to declare in court “If this be justice, then God help every woman!” Later she pronounces, “I came here to laugh at these fool women — who never stop to think that all they have depends on the selfish whims of some man.” Indeed, every man in her life, except the engineer she loves, is an exploitive rascal.

The allusions to Young’s real-life press scandals in this story, which presents her character as martyred to the same, is a curious “meta” element similar to the way Lana Turner would later star in soapers about wronged women accused of murder. This film was among several produced by Young’s currently scandalous lover/manager Harry Garson, and the plot feels like a way of acknowledging Young’s travails and even exploiting them while also deriving sympathy for them.

This tinted 16mm print, remastered with a new score by Serge Bromberg, bears no comparison with an older edition floating around from a couple of sources that, while seemingly the same in content, is infinitely more ragged and worn. It’s not of “shot yesterday” quality but it’s good enough for Arthur Edeson‘s photography to be appreciated and without physical deterioration getting in the way of absorbing the story.

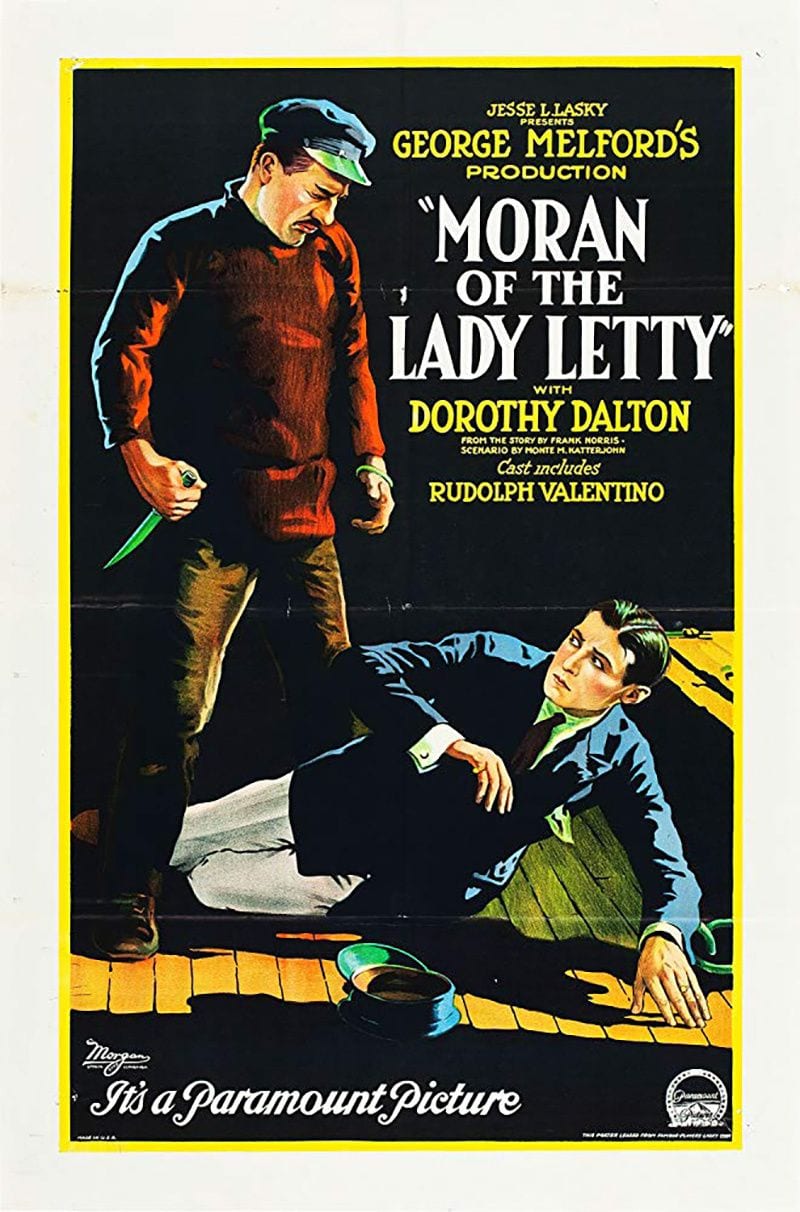

The 1996 restoration of a 35mm print of Moran of the Lady Letty (1922), newly tinted, does boast that sparkling “shot yesterday” quality, as seen in the previous DVD edition. This is the film Valentino and director George Melford made as a follow-up to the thunderous success of the previous year’s The Sheik.

As a change of pace, instead of being “exotic”, Valentino now plays a bored, home-grown California playboy “of Spanish descent”, one Ramon Laredo, the object of adoration from fluttering lovelies and the eyebrow-lifted envy of his fellow “tango hounds”. Ramon wishes he could “chuck it” and “run away” to some exciting life. His wish is granted when he’s doped and shanghaied aboard a ship with crooked Capt. Kitchell (Walter Long) who, in the space of two minutes calls him “a dancin’ master”, “angel child”, “dearie”, and finally the nickname that sticks: Lillee of the Valley.

Ramon is doubled, and even anagramed, by the parallel story of the titular Moran (Dorothy Dalton), who was raised as a “seaman” by her single father (Charles Brinley). A tomboy in a pageboy haircut and dungarees, she’d passed Ramon on the dock and called him “a softy in a minstrel suit”. These aspersions on Ramon’s manhood, which he will spend the story dispelling with his fists and his love for the tomboy, are another example of a film exploiting snide gossip around its star’s reputation by incorporating it into the scenario. In real life, for questioning his masculinity as a “powder puff”, Valentino challenged one reporter to a boxing match.

“I never could care for a man — I’m not made for men,” says Moran to him at one point, later adding, “I ought to have been born a boy.” The legacy of their strongest friend aboard, the Chinese cook (Walter Kuwa), is to give her a dress because, as a title card states, when a man makes love to a lady, one of them should wear a dress. One of the most poignant details in their relationship is the way they call each other “mate”, which can be understood sexually or platonically. Here’s a curious example of two characters finding affinity while both are questioned for non-conformist gender demeanor.

This print is so clear that when the characters stand outside a movie theatre, we see it’s playing two films of 1920: Rex Ingram’s Under Crimson Skies with Elmo Lincoln, and a chapter of Edward Sedgwick’s lost American Fantomas serial. How we want to buy our ticket and have a look.

The four films on Volume 2 include the other three films from the old DVD set plus a newbie that’s of course also an oldie. The repeats are the two surviving reels of Edmund Mortimer’s five-reel A Society Sensation (1918), the three-reel cut-down of James Vincent’s six-reel Stolen Moments (1920), and a reconstructive attempt on Philip Rosen’s mostly lost The Young Rajah (1922).

A Society Sensation is by far in the worst shape physically, and what we see of the story does it no favors. What’s most revealing about this film, besides Valentino’s two-piece bathing suit, is the way even this pre-stardom item presents him as a sex symbol whose vision stuns all onlookers. His character of rich playboy Dick Bradley is introduced emerging from the ocean like a male Venus, instantly catching the eye of the whole cast, including a fisherman’s daughter (Carmel Myers) whom he’ll later rescue from kidnapping aboard a yacht. When it’s established that she’s somehow a duchess, she’s no longer beneath him, class-wise.

Looking much better and also wearing pretty well, Stolen Moments was very attractively shot in Georgia and Florida and uses lots of evocative lighting effects in its final reel. This print looks nice and contains a few blue-tinted outdoor shots. The last film Valentino made before his stardom in The Four Horsemen, this effort casts him as a wealthy mustached Brazilian novelist in spats. He’s a heel and a scoundrel who tries to convince a pure American heroine (opera star Marguerite Namara, who doesn’t employ subtlety in her gestures) that they should run away without benefit of marriage. “Ours is a love that’s above such stupid conventions.” Later he tries to blackmail her and gets what’s coming to him, proving you just can’t trust those handsome Brazilians.

The exotically attractive yet morally bankrupt foreigner who threatens American womanhood was a dramatic type of this era. The most famous example was Sessue Hayakawa‘s wealthy Japanese character in Cecil B. DeMille’s controversial sensation The Cheat (1915), although that highly ambiguous movie shows him to be a man of his word while the American woman “cheats” on their deal. The secret of that movie, and of Hayakawa’s appeal as a sex symbol for the rest of the decade, lay in his very desirability while the story worked overtime to avoid moral compromise. By the time Valentino came along in a variety of ethnic roles, women were apparently ready to compromise. He hadn’t quite broken through yet, however, so our heroine successfully resists his contemptible advances.

Overcoming her “prejudice” (named as such) is a major plot point for our heroine in The Young Rajah, a costly Paramount epic cashing in mostly directly on The Sheik. Mathis, who was writing most of the actor’s scripts at this point, adapted it from the 1895 novel Amos Judd by John Ames Mitchell, an interesting literary figure and architect who co-founded Life magazine.

Pulling off the trick of being simultaneously “exotic” and “all-American”, Amos Judd (Valentino) is the son of an Indian maharajah and an Italian countess. After a coup usurped his throne as a child, he was adopted and raised as American by Joshua Judd (Charles Ogle, the screen’s first Frankenstein monster from 1910) and attended Harvard, where he became a star on the rowing team. This lets the camera show him off in nothing but swim trunks as he strokes away in the skiff. A title card, apparently speaking for the world, declares “Mr. Judd has such wonderful muscles and such magnetic and soulful eyes!” They were still selling him, and the audience had already paid for the ticket.

Since he’s descended from the legendary Prince Arjuna of The Mahabharata, Amos bears “Krishna’s fingerprint” on his forehead, which allows him the gift of prophecy. This causes some trouble involving his destiny, which calls to him from his old existence even though he’d prefer to stay American and marry Molly (Wanda Hawley). According to Wikipedia, Mathis believed in reincarnation and mysticism, and remember that she spotted Valentino in a movie that also emphasized the mystic East.

“There are many roads — all lead to God,” says Amos to Molly in explanation of why he reads the Bible, the Talmud, and the Koran. Molly tells her father, “I couldn’t marry a man that was not of my own people, no matter how much I–I loved him.” Then, as if destiny guides her hand, she opens a book at random to the lines: “Men should be judged not by the tint of their skin, the Gods they serve… but by the quality of thoughts they think.” Her part in the plot’s formula will stress her progressive education for love. Amos’ part will build to his rightful place adorning skimpy costumes designed by Valentino’s then-wife Natacha Rambova.

Lasting not quite an hour, this reconstruction uses what minutes remain, in poor shape, of this largely lost feature in combination with stills, recreated title cards and plot summary. It’s likely we’ll never have more than this.

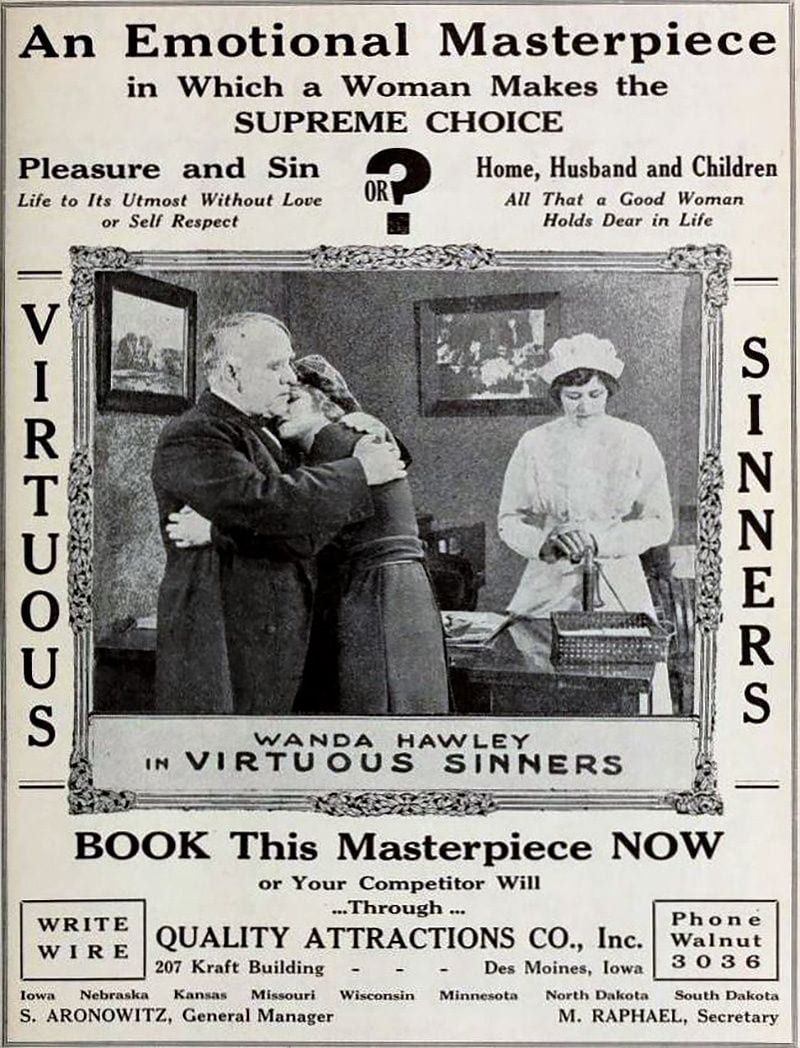

The disc’s new item is another pre-stardom feature. Running almost an hour, Emmett J. Flynn’s Virtuous Sinners (1919) can hardly be called a Valentino film except that he’s clearly visible in a small part in several scenes, especially at the hospital and the trial. He looks very much like the youngest of the gang. The stars are Norman Kerry, who reputedly encouraged the young actor to try his luck in cinema, and the same Wanda Hawley who would be his leading lady in The Young Rajah.

Virtuous Sinners belongs to the day’s popular trend of sentimental Skid Row dramas, an urban genre set among orphans, outcasts and shady characters. The opening sequence of sheer misery finds our bedraggled heroine, symbolically named Dawn (Hawley), standing in the rain looking through a diner’s window and then going home to be beaten by a brute who casually mentions that he deceived her with a fake marriage ceremony. At least it frees her to walk out. This kind of set-up wouldn’t be permitted in the talkies after the Production Code crackdown of 1934.

The rest of the drama takes place amid the society of a charity shelter where Dawn takes up residence and plays the piano. One night, her voice attracts Hamilton Jones (Kerrigan), one of the era’s dapper top-hatted “gentleman burglars” inspired by E.W. Hornung’s Raffles and Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin. He’s so bewitched by Dawn that he donates some of his ill-gotten funds to the cause. His romance is interrupted by a tragedy that leads to a trial and two distinct endings, first the immoral ending and then the virtuous one.

This is a good movie that observes the interactions of several characters in a well-conceived milieu and distills that Hollywood formula of humor, heartbreak and hokum that was already so well calibrated. As the title implies, most characters are a mixture of the virtuous and sinful. Photography and design are excellent, as is made clear by a Library of Congress print that’s very clean and sharp until noticeable deterioration begins flitting across the image at the halfway point. Robert Israel provides the score, as he had done on several of these titles.

Despite the Valentino connection, this is the sort of title that would probably never get its own release, especially with its incipient decay. It’s good to see it freed from captivity, reminding us that thousands of perfectly serviceable and culturally revealing silents still languish in our archives, awaiting the Dawn.

- Rudolph Valentino Collection, Vols. 1-2 (Blu-ray M.O.D. Editions) on ...

- Rudolph Valentino Hollywood - YouTube

- Rudolph Valentino Collection, Volume 1 (Blu-ray) (2018) - Flicker Alley

- Flicker Alley (@flickeralley) | Twitter

- Flicker Alley - YouTube

- Flicker Alley - Home | Facebook

- Flicker Alley – Bringing Film History to New Audiences