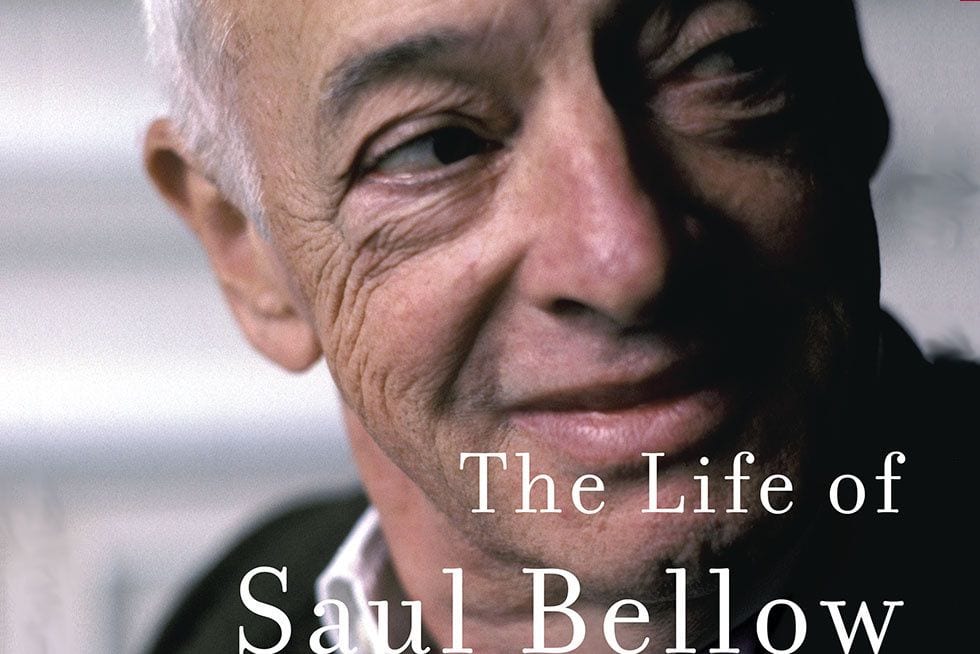

The legitimacy of Saul Bellow as among the greatest 20th century American writers has never really been in dispute. Recipient of (among many awards) the Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes in 1976, and three-time winner of the National Book Award (1954, 1965, 1971), the Canadian born and Chicago bred Bellow mined the world of the displaced Jewish-American male as he sought his own place in the world. Despite the accolades, in Below’s work women are perhaps best appreciated as dispensable, like brand new cars to be appreciated for a while and eventually returned for newer models. Early novels like Dangling Man (1944) and The Victim (1947) mine every drop of existential angst in the transition at the end of WWII and everything else that followed. The Adventures of Augie March (1953) establishes Bellow as a picaresque comic master, followed by more doom and enlightenment (1956’s Seize the Day and 1959’s Henderson the Rain King).

It’s easy to list the credits and highlight pull quotes from these novels (particularly everything from his third book onward). They don’t need any further justification as pillars of that abstract house that encompasses all Great American Novels. They were written and elevated during an American culture when the white male was the king of it all. Such men wore dapper suits and fedora hats. Struggles were encountered, but the ingenuity of these men was always going to save the day. Political complications and class struggle were always there, but Bellow stayed on the sidelines. Everything expected about the doomed fatalism of the Capitalist structure in Seize the Day, for example, is implied and carefully spelled out through images and poetic passages. Indeed, Bellow was a careful craftsman who saw no need for angry polemics.

As we enter Bellow’s life and work in the mid-’60s, flush off the success of Herzog (1964) and his second National Book Award, those who start Zachary Leader‘s thorough The Life of Saul Bellow: Love and Strife 1965-2005 without any understanding of the man’s work (let alone his life) might feel a little lost. Leader’s first volume, The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune, 1915-1964, offered all that and more about this man who was a resident in the United States without papers until he was 28. Leader’s apparently unrestricted access to Bellow’s papers and more than 150 of the novelist’s family, friends, colleagues, and paramours was measured and precise as it established the building blocks of the man and his work. Women come in and out of his life (a habit that will continue through Volume Two), alliances are formed and broken, children are embraced and estranged, but through the end the muse is obeyed.

The question Bellow apparently asked at the end of his life is a fitting way to start this second volume: “Was I a man or was I a jerk?” It’s a fitting question to ask as we enter the world of late-1964 Bellow. Herzog has just been published. The novel, a masterpiece that blossomed from the end of his second marriage, carefully but without a doubt transposed the lives of ex-lovers and former friends into literary gold. By the time he turned 50, Bellow was famous from a book that took no prisoners and set the standard as to how that question might be answered. He was apparently a jerk who betrayed everybody and everything in his life but the work.

Leader carefully and precisely accounts for the women who come in and out of Bellow’s life. By 1968, in the final stages of writing Mr. Sammler’s Planet (one of his more problematic novels) he was juggling three lovers while married. More women were procured while on lecture trips and visiting fellowships. The love starts from a mutually shared literary enthusiasm, but soon it mutates to anger. A bitter divorce initiated in the late ’60s compels Bellow to lie about his income and fill his work (particularly the 1975 masterpiece, Humboldt’s Gift) with anger and vengeance. Was Bellow oblivious to the damage his sons were experiencing from the domestic turmoil? Perhaps this happens when a man has a son with each of his first three wives. “I am bristling with Lilliputian arrows,” Bellow writes, imagining himself a crucified Gulliver in the land of the little people. “They itch horribly.”

Leader provides a good deal of space early in this book to the genesis of (and reactions to) 1970’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet, and the reader’s reaction to it might mark the point where they either get off the Bellow bandwagon or process it as yet another factor in his life that needs to be understood within context. The novel is the first of Bellow’s to not only directly address the Holocaust, but also to look at racial divisions and identity politics within the tinderbox that was ’60s-era America. Sammler is an old soul, a man out of time, facing a resistant leftist audience at Columbia. Where other writers of the time (particularly Norman Mailer) would willingly and controversially confront race in their work, Bellow took it one step beyond. Sammler is accosted and sexually violated by a young African-American man. Sammler sees the man, in all his threatening nakedness:

“What was being demonstrated was not merely the black man’s potency, but Sammler’s impotence… the novel… can be read as an inversion of [Norman Mailer’s] ‘The White Negro,’ inspired by the same fantasies and imagery.”

Leader continues: “More puzzling than Sammler’s racism is the violence of his reference to female sexuality.” Leader quotes critic Morris Dickstein: “No writer since [Jonathan] Swift has built his work on such a fascinated repugnance toward female odors and female organs, or expected them to hear the onus of representing a whole culture in decline.”

The modern reader might ask whether or not these are the best times for a monumental biography of Saul Bellow. Leader diplomatically and carefully illustrates the problems in the writing of (and reaction to) James Atlas’s single-volume biography Bellow (Modern Librarry, 2000). Confidences were developed and betrayed. Atlas was recommended to Bellow by fellow writing legend Philip Roth, and the reader wonders if there was a backlash to the way that turned out. New York Times writer Brent Staples also doesn’t escape Leader’s criticism as a writer who could not see the difference between criticizing, stalking, and seeing the man’s death as an opportunity to write the definitive obituary for the paper of record.

The question of whether or not somebody like Saul Bellow has been demoted from the canon will always be political. His work is not so frequently quoted as Roth’s, John Updike’s, or John Cheever’s. He has long been championed by young lions of the ’70s like Martin Amis, but even there it’s an endorsement from a European who (it can be argued) has long been able and willing to see the culture of the United States in a more clear-headed manner. Indeed, it can be clearly seen by the end of this book that while Leader might not be making a case for Bellow as the novelist of the century, he’s probably the emblematic white male novelist for his time, for better or for worse. What’s troubling and difficult to contextualize (let alone simply absorb) is reading Bellow’s exhaustive pattern of behavior with women in his life and work, with the Left-wing ideologues who seemed to embrace him through at least the first half of the 60s, and with a stubborn need to mine everything from life for the purpose of his work. If a criticism can be made of the style Leader employs throughout this book ,it could be that he doesn’t look at influences and ideas as ingredients that make for great novels. Leader knows the work better than perhaps anybody save for Bellow himself, but the knowledge of the work is mainly for data and structure, not necessarily for literary style.

The Life of Saul Bellow: Love and Strife 1965-2005 works best in smaller scenes of humility and tradition. We go through academic positions, (especially at Boston University), debates with PEN colleagues, friendships and estrangements, women and money troubles, and the growth of his work as he went from the epic bildungsroman of The Adventures of Augie March to smaller jewels like A Theft (1989), The Bellarosa Connection (1989) and The Actual (1997). It’s probably not likely that a writer with a reputation other than Bellow’s could have published such compressed stories as singular books, paperback originals, but these smaller books were minor in size only to the more substantial works. Leader knows the work, but he ends with a scene at Bellow’s funeral in Brattleboro, Vermont. Martin Amis and Philip Roth were already there before much of the extended family.

“During the funeral, Philip Roth told [literary agent Andrew] Wylie, ‘I wonder if the earth knows what it has just received.’ “

Leader continues, connecting the obvious grief of the still living literary titan and how he channeled it into his own work:

“To Ruth Wisse, it was Philip Roth who… seemed to wander around all day with his mouth open, looking lost… Within a year, he published a short and harrowing novel Everyman (2006), which begins with the protagonist’s funeral…”

Leader includes two pivotal and extended passages from Roth’s Everyman, and the reader familiar with it will see the connection between that meditative book about death and a father who describes his sons as “the source of his deepest guilt”. That generation is basically gone now. It’s unlikely Bellow’s rather prickly personal reputation will be rehabilitated enough so that his work can be rightly placed in the pantheon with (and at times above) Roth’s, but that’s not the issue as we close this look at the life and times of Saul Bellow. Leader’s subtitle, Love and Strife, certainly applies here. Those deeply familiar with Bellow’s novels and stories will appreciate Leader’s astute criticism and understand why the decidedly minor nonfiction and theater work is not as deeply examined. Leader provides more than enough material to give his reader a head start into a deep study of some important, challenging, controversial, brilliant, distinctly American literature.