Americans who are only familiar with Scarborough as a British resort town with a prestigious fair, may be surprised to learn there is a very different Scarborough much closer to home.

Scarborough is a community in the east of Toronto, Canada’s largest city. The community has a reputation for being riddled with poverty and crime (in fact, crime rates are higher in Toronto’s west end, and its downtown waterfront and entertainment districts have the worst crime of any part of the city; but impressions will be impressions). What Scarborough does have is diversity: over half the population is foreign-born, and over 60 percent are visible minorities. It has one of the highest numbers of low-income family neighbourhoods in the city (Toronto, which is Canada’s most diverse city, is itself notorious for having the second largest income gap in the country).

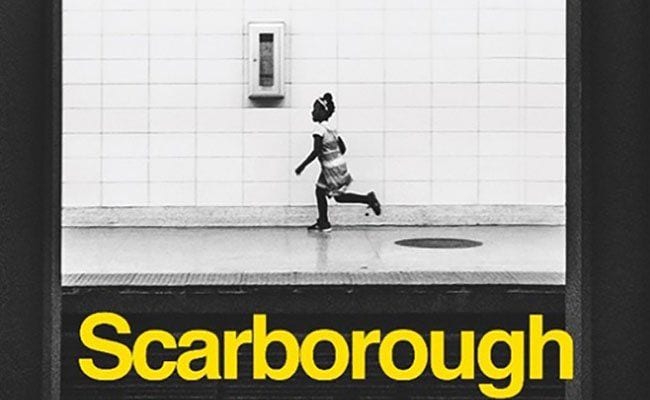

A slice of its complex story now emerges in the powerful novel Scarborough. Author Catherine Hernandez is a theatre practitioner who previously published the children’s story M is For Mustache: A Pride ABC Book, celebrating LGBTQ families. This is her first novel.

Scarborough is a powerful telling of the community’s stories. Told from the perspective of over a dozen different narrators, many of them young children attending a neighbourhood literacy program (where some of them receive their first meal of the day), it offers a glimpse at the diversity of experiences the neighbourhood is comprised of. They are Indigenous; they are immigrants; many of them are poor and underfed. They attend school next to children from much higher-income backgrounds. Their parents’ stories are complex, too: single parents fleeing abusive partners; abusive parents struggling to get their lives on track.

The book portrays life in this community whose poverty of income is complemented by a powerful richness of life. Stylistically, the book has a magnetic narrative appeal which is surprising, given its lack of a single plot line. Instead, the profusion of characters whose lives are interwoven, and the multiplicity of perspectives provided by the narrators, generates a self-induced narrative momentum of its own. The characters’ lives run up against each other and their struggles intersect as they each approach personal climaxes about which the reader finds that they’ve come to deeply care about. Scarborough is important for many reasons; it’s also quite simply storytelling at its finest.

While Scarborough is very much written for adults, much of it is experienced through the eyes of young children. Hernandez felt that in order for readers to understand the realities of what her characters were experiencing, “if they looked through the eyes of mostly children, they were going to understand very small nuances of emotion, of character, of plot.”

“[Children] are always observing,” says Hernandez. “It was a tool to make sure that the people who were reading it were going to fully understand the world in which Scarborough resides.”

A Message to Management

The variety of characters generates several interlocking plot threads, and the point of intersection for many of them is Hina Hassani, a community worker employed by a large agency which runs literacy programs throughout the city. Hernandez centres the experience of this young Muslim woman as a key protagonist in Scarborough’s story.

The structural challenges of Hina’s job will be instantly recognizable to many who have worked in community agencies. She’s full of energy and idealistic hope; empathetic and eager to care for the children and families she works with. Inevitably, she comes up against the community agency’s management: university-lettered ‘experts’ who lead via email from swank offices elsewhere in the city. Management frowns on Hina’s provision of food to the children — the focus should be on literacy, not on food — and leans on Hina to do unpaid promotional work beyond her regular hours. Her emotional involvement with the children and their families is admonished as potentially problematic; she is denied time off when she needs it for personal reasons.

Despite Hina’s daily first-hand struggles at the heart of the community, the social workers who manage her think they always know better. The deteriorating relationship eventually requires intervention from her union.

Hernandez, who ran a home daycare for several years and is intimately familiar with programming available for young children in the region, knew from first-hand experience how important providing food — one of the key points of conflict with management — is for children in the area.

“The food is a very big part of the programs. Because sometimes you have low-income children [for whom] that’s going to be their first meal of the day, coming to a program. So they’re offering food, but at the same time not being just about [offering food], so that they could spare them the stigma of being offered free food. It’s really important to a lot of these program leaders. So in a way [the book] was an homage to them and the communities that they serve. All of these decisions are made in offices far away for these programs, but not knowing what the impact is on these particular neighbourhoods.”

Conflicts like these are only the tip of the iceberg for community workers, who often find their work under threat from management and public officials alike.

“Every time there was an election, there were all these frontline workers either doing social work or running programs for youth in Scarborough that were holding their breath and worrying about the future of their programs. And worrying that with every new government… it might mean that all of that, all of those years that they spent outreaching to a particular community, would be lost in the blink of an eye.”

“For a lot of frontline workers that I’ve known in my lifetime, there were countless conversations that I’ve had with these people where they would say ‘My manager did this, this, this and this, that was abusive. And I wish I would have said this.’ So I really wanted to author into being the possibility of Hina actually being the kind of person who would clap back. I wanted that conversation — the conversation that could have been crafted by all of these people — happening in my book. I didn’t want it to be yet another person who is of colour, who is under the thumb of management.

“[Management] that is not racialized, that is privileged enough to have several letters after their name on a business card sitting in some clean office while they [the workers] are surrounded by people who might have bedbugs and might have lice and all this stuff, and the people at the offices saying ‘I want this particular report done in this particular standard.’ Something as simple as that — that’s a very typical thing that a lot of frontline workers say — ‘How in the hell am I going to have enough time to report in the way that you want me to report when I am working 60 plus hours a week trying to get this community on its feet?’ And you know these are people that are having to change their clothes in the parking lot because they’ve dealt with people with bedbugs all day. You have to have compassion for that!

“So I wanted, out of compassion for them, for them to be able to say everything that they wanted to say, but [don’t] have the privilege to do so, in my book. Because it’s my book.”

While the book contains its share of grim and tragic moments, it’s also deeply uplifting. Many of the children and their parents find unexpected allies in their struggles. Hina prevails over her overweening manager. For every tragic outcome, there are also triumphs.

“All of these things are possibilities. It’s absolutely possible to have management check themselves, and my hope is that people who are in social work and in management are reading it and I’m hoping that they are going to recognize themselves and check their behaviour.”

Scarborough as Metaphor

While Scarborough’s many stories deeply deserve to be told, the book also grasps at something beyond the east-end Toronto neighbourhood; something that resonates more broadly in Canada’s growing urban geography as well.

“It’s about the other. Usually when I read it in other communities I always ask ‘What is your Scarborough?’ And they always have an answer. Every city has an answer. Because of race, because of classism, you have this idea of where all of those people go. Where can those people afford houses? Where do those people go to school? Where do we not want those people? That’s very much what Scarborough is about.

“We are the eastern edge of Toronto where most of the brown and black folks can afford to live. That means that most of our commutes — if we are working in downtown Toronto — that could be a two hour plus commute into town, depending on where you live. Being a working class community, imagine what that means to how you parent children if you are low-income and you’re making minimum-wage downtown, then coming all the way back east to Scarborough. And they already have the bad rap because there are already so many brown and black people here.

“There are assumptions — when people are low-income — assumptions as to what the safety is here. When in actual fact any crime that happens here in Scarborough can easily happen downtown. In some ways I feel safer here than I do downtown, simply because as a brown woman, as a queer brown woman, I don’t feel safe downtown a lot of the time! I feel like I’m constantly stared at, that I’m judged. Whereas in Scarborough I just feel much more myself because of the fact that I’m around a lot of people that look like me.”

Writing, Representation and Accountability

Scarborough comes at a pivotal moment in the Canadian literary scene. Many of Can-Lit’s icons have been bruised and tarnished by scandal and pride. Last year, prize-winning author Steven Galloway was let go from his position as head of University of British Columbia’s creative writing program amid accusations of sexual harassment and assault. A who’s who list of Canadian literary stars lined up to defend him, earning the ire of a younger generation of writers and readers. Feminist icon Margaret Atwood herself rushed to his defense in an inexplicable series of Twitter tirades and public commentaries.

Then the CBC, traditionally the country’s premiere patron of the arts, sparked controversy with its annual battle-of-the-books Canada Reads competition this year. Its quick dismissal of Indigenous women’s work garnered accusations of misogyny and colonialism from newer literary voices.

Most recently, award-winning author Joseph Boyden has been engaged in a protracted scandal that began in December 2016, when the APTN news agency published an investigation into the shifting claims of Indigenous identity Boyden has made over the years. After months of controversy, Boyden responded in a 2 August article for Macleans magazine, where he defended his Indigenous identity, drawing in part on family stories, his solidarity work with Indigenous communities, and DNA testing. His response only inflamed the controversy, and broader debates over representation and authenticity in literary production.

As Canada’s ancient regime of literary elites self-destructs, the country earnestly needs new literary heroes — ones that offer not just new literary voices but new literary ideas. Ones that offer new ways of doing literature that reveal its possibilities and potentials as we move into a new century, and as the perspectives and expectations surrounding literary voice change as inexorably as the peoples whom the country’s literature seeks to represent.

Juxtaposed against the wayward flailing of Canada’s old guard literary elite, Hernandez offers a carefully thought out creative model for ensuring that literary works remain accountable to those they depict and represent.

“I was once asked to facilitate a panel discussion with an organization that said that they wanted to do ‘very difficult conversations’ — like what they considered daring —

about race, about sex, about politics and stuff like that. And my particular panel was specifically about cultural appropriation. About when is it your story, and when is it not your story, and if it is not your story what do you do then? And funny enough, the only people of colour — because of the ticket price for this particular event — were on the panel! So here we are, one Indigenous person, one black person, and then myself an Asian-presenting person. Up there, about to talk about when is it right or not right to appropriate our culture. And meanwhile everyone in the audience is white! And we had to have this conversation.”

“So first of all, you have to admit it: I am guilty of wrongfully representing particular cultures. [At the panel], I opened up with a story about the fact that we were writing a play about a Filipina caregiver and even though I was a caregiver at that time, the truth is I wasn’t a live-in caregiver. I’m a Canadian citizen. So there’s all of this privilege I did not take into account, and during my research I didn’t realize so many things that were wrong about the way that I was researching this community. I assumed that they might have time off to talk to me, I assumed this, I assumed that, all these missteps. And then I had to admit it. In order for me to solve the problems, and in order for me to honour them properly.”

“If you have a play, you have to ask, Is this my story to tell? If it’s not, don’t tell it! If it’s something that you feel is really important to you — for example, there were numerous characters in the book where they were not of my culture — so I paid people to check me on it. Is the terminology right? Is this right? Is the character right? Do you feel that it’s real? All these things! Please tell me. Be honest. And they did! And I was very happy to receive that feedback, to change things. I would be open to the person saying ‘This is bullshit. I don’t like it. Stop it.’

“There have been two projects that I’ve done in the past where I felt that it was a good idea, and it wasn’t. And I had to be open to that. That if people were like ‘This is not a good idea, and I’m from that community, and I’m offended by you trying to do this,’ I had to be open to it. You have to be open to that, because of the fact that if you are actually an ally, it means that you are going to be listening to that particular community. That’s a really important thing. If you are creating work that is about someone else, it means you have to honour that community.”

The same techniques Hernandez developed in theatre were ones she applied to her work in fiction, as well.

“You sort of have this residue of the people that you’ve met. So you build and you craft this person from your own imagination and then you check in again with people who are from that particular culture to make sure that it’s correct. And you pay those people in whatever way you want to pay them, be it through food or through payment. It’s just really important to have those people be paid for their time to check you because of the fact that it’s not your culture.”

In discussing the challenges facing Canada’s literary scene, Hernandez is not so much interested in criticizing its flawed icons as in encouraging people to turn the same critical spotlight on themselves.

“When it comes to Boyden, I wish that we weren’t so much focused on his own personal story, and instead going to ourselves and saying, well, ‘How can I do better?’ For people who are allies to Indigenous cultures or to brown and black culture, instead of just pointing fingers at one person — it’s just like these Americans saying ‘Oh Trump is so evil, Trump is so evil.’ Actually, there’s Trumps in all of us! So where is the Boyden in all of us? And how can we improve on that? That’s what I think is the number one thing we have to keep on asking ourselves.”

“And as much as you can come up with procedures or a list of guidelines for people, the truth is that, for me, the guideline is more like, Keep on asking questions. Be open to being called out. Make changes. Keep going. It’s as simple as that. Those are the guidelines. It’s to say that this is an ongoing discussion. And it doesn’t matter what you think about yourself — you didn’t buy yourself out of Racistville.

“Like, I am now officially a Navajo wife. I’ve now married into the tribe. Am I going to stop being a Navajo ally? Am I going to pretend that I’ve bought into the culture and I’m now sort of magically, like there’s been some sort of magical fairy dust that’s been put over my head and all of the sudden I understand what this particular community’s challenges are? No. And can I speak on behalf of them? No. It means that I still have to check myself and I’m even more responsible to this community, because of the fact that I am now part of this family.

“So it’s [important] never to settle, never to rest on your laurels. That’s part of activism, you just have to know that it’s never done. The work is never done. And it’s the same thing with writing. I can always do better. I can always do better with my writing and representing people.”

Hernandez, who recently took a position as artistic director with the theatre company b current Performing Arts, is already planning her next book, which is tentatively titled Crosshairs and depicts a world in which black, brown and LGBTQ people have to militarize themselves against white supremacy.

“It just asks the question, what would happen if this entire legacy that is happening — and it’s not about Trump, it’s about the unveiling of what white supremacy already looks like already — what would happen if it goes to a point where we do have to learn how to take up arms?” she explains.

It’s a grim concept. But if anyone is capable of handling difficult truths with empathy, respect and creative skill, it’s Catherine Hernandez.