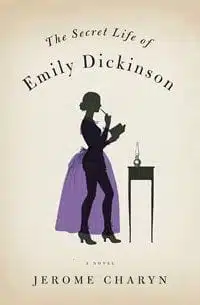

The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson takes readers through the surprisingly adventurous, often chaotic, and most likely fictitious life of the poet Emily Dickinson. While Dickinson’s beautifully simple and occasionally blunt poems, such as “Because I could not stop for death” and “Wild Nights, Wild Nights”, are well-known and often required reading in American high schools and colleges, much less is known about Dickinson’s personal life.

As such, rumors and stereotypes abound, i.e., the reclusive spinster/old maid poet mending her broken heart and wasting away in her father’s attic. Author Jerome Charyn attempts to break free from these stereotypes. He presents a Dickinson who, in his words, could be “bitchy, petulant, and seductive, and also a mournful, masochistic mouse in love with a mystery man she called ‘Master,’ and to whom she would have sacrificed all.”

For the most part, Charyn succeeds. Freely mixing fact with fiction, Charyn creates a kaleidoscope of a character in Dickinson. His Dickinson lusts after a handyman while boarding at Holyoke, visits rum resorts with her huge dog Carlo, attempts to elope with a gentleman she dubs Domingo (after the rum), and still finds time to become an expert bread baker.

While numerous characters in the book (such as Sister Sue, Austin Dickinson, Edward Dickinson, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson) were actually real people in Dickinson’s life, Charyn adds a few characters (and settings as well). An administrator at Holyoke, Miss Rebecca Winslow, introduces Dickinson to poetry – a nice touch to the story, but completely fictional. Dickinson’s sometimes friend and sometimes rival Zilpah Marsh is also completely fictitious, as is the insane asylum Marsh is committed to later in the story.

While fictional, Dickinson’s relationship with Marsh is just one way that Charyn develops Dickinson’s character and shows many of her flaws. In the introduction, Charyn states, “I wasn’t interested in writing a novel about a recluse and a saint.” Dickinson’s relationship with Marsh is anything but saintly. Only pages into the novel, Dickinson lies to Marsh and attempts to bribe her, all because of an interest in Tom the Handyman – a man Dickinson has never even spoken to.

Their rivalry continues when Marsh becomes employed in the Dickinson household. Later, when Dickinson prepares to fire Marsh, she acknowledges: “I am cruel. I want Zilpah Marsh to die. She has my Tom in her bed. Her cul-de-sac is a kingdom. I choose my words like a rapier that can scratch deep into the skin.”

Charyn ends his introduction by stating, “I hope my Emily will both delight and disturb the reader and take her roaring music right into the 21st century.” Dickinson’s relationship with Marsh should disturb most; however, finding the Dickinson who delights is a little more difficult. But there certainly are a few moments. The picture Charyn draws of Dickinson’s relationship with her dog Carlo is charming. Dickinson confesses:

Lord, I’ve been truer to Carlo than to any man, including that other rascal, Tom the Pickpocket. The Pup has seen me cry, throw jealous fits, plot against Pa-pa, thunder around like Zeus himself, and he’s like a peace officer who can calm his mistress and make her laugh. I cannot recall being lonely in his presence.

Perhaps more than a delightful Dickinson, Charyn portrays a lonely, mournful Dickinson. She has numerous illnesses and ailments and, for much of her adult life, was forbidden by her doctors from reading or writing. She lusts and longs after various men, but her romantic notions are ultimately thwarted. After each disappointment, Dickinson becomes more troubled until she tells us: “I became a hermit within my father’s house. When the butcher boy knocked on the kitchen door; I fled – his fairness troubled me … I did not want to be reminded of Tom the Handyman in the tousled hair of a butcher boy.”

As promised, Charyn does many unique things with Dickinson’s character; however, Charyn’s greatest triumph is perhaps the novel’s voice. He tells us that “the novel will be told entirely in Emily’s voice, with all its modulations and tropes – tropes I learned from her letters, wherein she wears a hundred masks.” Indeed, Dickinson’s voice comes through clearly. We hear it at the story’s beginning when she waxes poetic over Tom – “Lord, I do not know what love is, yet I am in love with Tom, if love be a blue arrow & a heart that can burn through skin and bone. Tom and I have never spoken. How could we? … Still, I watch him in the snow … ” This voice is still there when we hear from a more mature Dickinson whose health has begun to fail:

My eyes have begun to bother me, and I totter across the street to a little quarter. I have never felt such vertigo before. I can find nowhere to rest – my eyes are seared with fire and seem to jump out of my skull. That is the last thing I can recall … until I catch myself afloat in a blinding white fog. There is a buzzing in my ear…

Dickinson’s voice always comes through clearly, except when she is not the story’s narrator. The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson is divided into seven sections, and almost every section ends with several pages of third-person, omniscient narration. This is a bit odd. To move to such a neutral and reserved narration style after pages of Dickinson’s rambling, poetic, and/or chaotic thoughts is, at times, jarring and distracting.

Thankfully, though, Charyn let the final words be Dickinson’s. The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson ends beautifully, with a hodgepodge of imagery and memories laced with moments of regret. The last brief chapter is perhaps where Dickinson’s voice comes through the most strongly, and the story ends with the delighting Dickinson floating through the air and moving with “each palpitation of [her] heart”.