Most people know silent films as odd little herky-jerky eyesores. Most people know that silent films are black and white. Most people know that silent films are silent. Everything most people know about silent films is wrong.

The possibility for the public to have another look began in the VHS era, when sparkling prints of such landmarks as The Docks of New York and The Student Prince and The Wedding March trickled onto video, looking as fresh and modern as the day they premiered. Now we lucky denizens of DVD are in a golden age of appreciation for silent movies, as many are beautifully restored or digitally refurbished, tinted, and shown at their correct speeds with sensitive musical accompaniment. We understand that the talkies offered nothing thematically or aesthetically that hadn’t already been known in the silent era. As the double-disc set Discovering Cinema proves, that includes sound and color.

Each disc features an hour-long documentary plus many bonus films. The documentaries are Learning to Talk and Movies Dream in Color produced a few years ago in France by Lobster Films/Histoire. Presented here with English narration, they succinctly and intelligently summarize the technical developments of sound and color, which began with the earliest days of cinema. By coincidence, each element proceeded along three parallel tracks.

For sound, the simplest track was employing live sound in the theatre by hiring singers to accompany a film of somebody singing, or by leading the audience in a sing-along, or otherwise incorporating live performance. The documentary doesn’t mention this, but in Japan, a live narrator became an institutionalized part of the silent film experience, a fact that delayed the introduction of talkies in that country. The documentary does mention a few odd experiments, such as a 1920 serial that incorporated word balloons onto the image, and the German Noto Film process, where you see musical notation running along the bottom of the screen.

Without the fancy extras, this was how most audiences experienced “sound” in the silent era, through the live music. In this sense, a silent movie was never silent. Still, throughout the silent era, audiences were subjected to a barrage on novelties exploiting various techniques, so that the notion of watching a movie with sound was a familiar one long before The Jazz Singer in 1927, which history books often labeled the first talkie.

You may be familiar with one of the earliest films produced in Thomas Edison’s studio: two men dancing while a violinist plays into a gramophone. Now known as the Dickson Experimental Sound Film, this was also the first experiment with sound, although the wax cylinders containing the music weren’t linked to the film by historians until about 10 years ago. This is a forerunner to the sound-on-disc system that eventually led to The Jazz Singer. That Warner Brothers production employed the Vitaphone system, where the sound disc played in synchronization with the image. The Jazz Singer only used the device for a few scenes, and in fact Vitaphone was doomed, a dead end.

The future was optical sound, or the translation of simultaneous sound into “images” on the film itself (the soundtrack) that could be retranslated into sound during projection. Lee DeForest and Theodore Case were the pioneers in this field, and audiences had been seeing their experimental shorts throughout the ’20s. Among the extras is an important DeForest production from 1923, a performance of Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, who created the first all-black Broadway musical. The sound quality is very deteriorated, but some of the joy comes through.

We’re also treated to the Case films of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the somewhat less immortal Gus Visser and his Singing Duck, who perform “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me” with appropriate quacks. (This film is also included on the More Treasure from American Film Archives box, which throws in early sound experiments with President Coolidge, Eddie Cantor, and George Bernard Shaw. And since it never rains but we’re swamped, we’ll mention in passing that the new three-disc edition of The Jazz Singer is a veritable celebration of Vitaphone, with an entire disc of rare shorts and another disc with a documentary about “the dawn of sound”.)

Movies Dream in Color details three parallel tracks in the development of color film. Thanks to magic lanterns and such devices, spectators in 1895 were already well familiar with color projections when they were first exposed to the wonders of the Lumiére Brothers’ novelty, the cinematograph. The earliest color films were laboriously hand-colored, frame-by-frame, print-by-print. And the results were beautiful, moving hand-colored postcards full of magic and frivolity, especially the swirling cloaks of the innumerable “butterfly dance” films.

By 1904, Charles Pathé introduced the stencil system, a still labor-intensive but more productive process that took care of multiple prints at a time through a kind of silk-screening. This process essentially dominated the silent era until the change to talkies, albeit in the modified form of tinting the prints with blue for night scenes, green for forests, red for fires, yellow for fields of grazing grain, etc.

Tinting was so basic a part of film’s vocabulary that when a rare film came along in pure black and white, such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, reviewers remarked on it. This point had been forgotten by generations of viewers who squinted at old prints, because the tinting was the first thing to rub off, but it was rare for audiences in the high silent period to watch a feature in black and white.

That wasn’t the only thing cooking in the color pot. The documentary shows many competing systems that developed, flourished and died in an attempt to bring color photography to motion pictures. We see several examples of additive processes, which combined primary colors in various ways and through various systems, such as alternating filters, cementing multiple negatives together, spreading microscopic dyes into the emulsion, and other technical ingenuities.

The triumph of Technicolor, originally a two-color and eventually a three-color formula, lay in what’s known as a subtractive color process. That is, color filters are used to subtract wavelengths of light from the subject, rather than adding colors onto black-and-white photography. I hardly understand what I’m talking about, but this review isn’t supposed to be a lesson in optics anyway; just watch the movie.

Anyway, all the extras on the color disc (demonstrating applied, additive and subtractive processes) are charming and lovely, but the “stars” are naturally the early Technicolor experiments. There are beautiful Kodachrome home movies of New York from 1930, and the main attraction is the first three-color Technicolor short from 1934, La Cucaracha. Curiously, this film is the only element (and only as a bonus, not in the clips of the documentary) that suffers from what looks like a PAL-conversion affliction that makes rapid movement appear blurry.

It’s interesting to note that this Academy Award-winning landmark is full of Latinos (though the leading lady is Hungarian), but it introduces an important point about the philosophy of Technicolor in the Hollywood studio era. Today most viewers suppose that color is “realistic” because the world is in color, while black-and-white is somehow dreamlike or unreal. In classic Hollywood, the inverse was the rule. Color was “exotic”, to be used for fantasy, for the escapism of two genres in particular: the musical and the lavish historical epic.

Most people also suppose that all films weren’t made in color because it was too expensive. It’s true that color was reserved for certain expensive items and not for the quickie B pictures, but most of the big-budget A productions weren’t in color either, and it’s not because they couldn’t afford it. The reasons lay in this aesthetic philosophy of color.

Consider the most famous color films of the era, beginning with the first three-color Technicolor feature, Becky Sharp. The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, The Adventures of Robin Hood, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Pirate, Duel in the Sun, The Red Shoes, Blood and Sand, the musicals of Betty Grable and Esther Willliams, these are lavish escapist events of other times, other places.

Now consider Hollywood at its most serious and contemporary: Casablanca, The Lost Weekend, The Treasure of the Sierre Madre, The Best Years of Our Lives, Mrs. Miniver, Kings Row, the films of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, the noir films and Selznick-Hitchcocks like Rebecca and Suspicion. There was no lack of budget for these projects, but they were dark instead of light, more real than fantastic.

Discovering Cinema is an excellent crash course with delectable extras on crucial, little-understood subjects in early film history. This effort comes from Flicker Alley, a small company that, at intervals of a few years, came out with the silent feature The Garden of Eden and then the landmark serial Judex, and now seems to be picking up steam. They’ve also freshly released Valentino: Rediscovering an Icon of Silent Film, a dazzlingly packed two-disc set on the king of seduction.

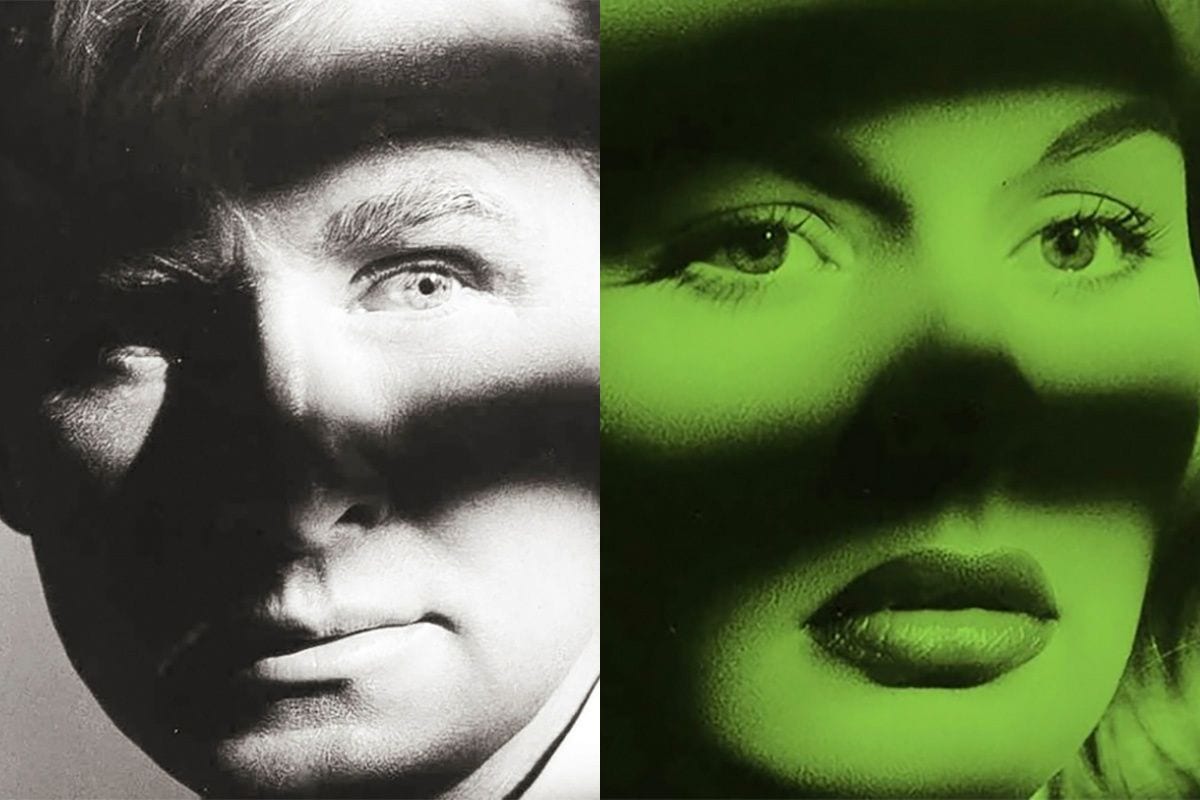

No star was sexier or more “exotic”, because Hollywood peddled to America the curious notion that sex was a foreign import. Sex was always an important dramatic element, but consider how it raised its ugly or pretty head in the films of Erich Von Stroheim, Cecil B. DeMille and Ernst Lubitsch. It was the province of extra-Americans (genuine or faux) who could be seductive or sinister. From Theda Bara to Anna May Wong to Pola Negri to Marlene Dietrich to Greta Garbo to Ingrid Bergman to Deborah Kerr, Hollywood imported women to have the kind of sex that midwestern female WASPs supposedly knew nothing of except what they saw in the movies.

The same was true of men. The clean-cut American hero could be counted on for two-fisted action with a modest self-effacement, but sex came under the tutorials of Von Stroheim, Sessue Hayakawa, Ramon Novarro, and of course Rudolph Valentino, whose name is variously spelled in these films as Rodolph, Rodolphe, and Rudolf. He’s so foreign that they don’t even know how to spell him!

The Valentino collection claims, somewhat inaccurately, to have digital reconstructions of two lost films, The Young Rajah and Stolen Moments, plus two other films, A Society Sensation and Moran of the Lady Letty. Actually, The Young Rajah is the only film subjected to what they mean by digital reconstruction, and at least a third of the film is intact, perhaps half. Stolen Moments and A Society Sensation are truncated two- and three-reel versions of previously longer features.

In chronological order, A Society Sensation (1918) is one of over a dozen films the Italian-born immigrant made before he broke into carefully-groomed stardom via The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in 1921 (and despite the malarkey heard on one early 30s tribute film included as a bonus, which claims he was lifted from the ranks of extras). During this period, his producers didn’t yet grasp the value of the “exotic” angle, so he was often a boy next door. Hastily re-released to cash in on his new fame, this two-reel version highlights the scenes with Valentino in a now rapidly resolved girl-meets-boy story. Among the supporting players whose roles are unfortunately reduced is Zasu Pitts, already recognizable for her gangly elbows and O-shaped mouth and missing only her distinctive moan.

Shot independently in Florida and Georgia, Stolen Moments (1920) was the actor’s last role before The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and they’d already tumbled to the exotic allure. He plays a Brazilian novelist who leads an impressionable Yankee lass astray. This three-reel reduction, like A Society Sensation and The Young Rajah, looks none too sharp, but the brief moments from an otherwise lost original tinted print look magnificent and make one yearn for what might yet be rediscovered.

Moran of the Lady Letty (1922), a follow-up to The Sheik made by many of the same people, casts our hero as a rich, bored “softie” of Spanish descent who gets shanghaied onto a modern pirate ship. In an arc similar to Captains Courageous, this does him a world of good. The captain dubs him “Lillee of the Vallee”. He meets Moran (Dorothy Dalton), the tomboy “seaman” who “should have been a boy” and “wasn’t made for men”. Aside from the two-fisted antics, this film seems to be about the normalization of gender roles, since she learns to wear a dress and kiss Valentino while he cures his namby-pamby ways.

The Young Rajah (1922) was long considered lost, but this version is based a fragmentary 16mm print that seems to contain most of the story after the opening act, which is reconstructed with stills and title cards. This is Valentino in full splendor as a fetishized object of sexy exotica (emphasized even more in heady production poses). He plays an Indian prince raised by an American family. He reads the Bible, the Talmud and the Koran and has a Buddha statue because “all paths lead to God” (a bid to overcome the Anglo heroine’s prejudice) and he’s also clairvoyant. This makes him a curiously passive hero, since he allows events to unwind around him.

The extras are many and splendid with all sorts of vintage promotional films and paper materials and dozens of photographs of the actor’s houses, pets, and memorials. The extras include a 1961 radio interview with the original “lady in black”, who annually placed a rose on the star’s tomb; and biographical material on many of the people involved in these films. In fact, the skimpiest biography goes, unfortunately, to Valentino. There’s no real discussion of his career ups and downs, much less a catalogue of “Who Rudy Slept With”, as is provided for several other people. Perhaps it would have required another disc.