Part 1: Prelude to Pepper

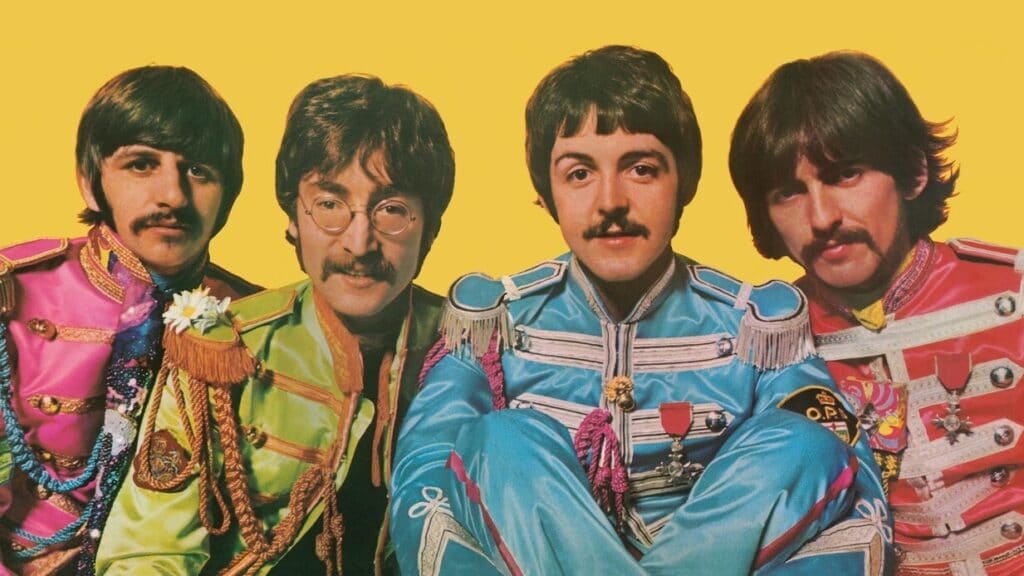

The most popular group in the history of popular music made many masterpieces. George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr created artistic works of untold musical, technological and cultural significance during their eight short years together as The Beatles. Help!, Rubber Soul, Revolver, numerous others. But one album, in particular, caused more commotion than any one of their other long-players. It was an album that introduced relatively new ideas to the group’s immense audience in the form of an overall “concept,” intended to give the songs a unified, cohesive feel. This album was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, 39 minutes and 13 songs performed and packaged in the most outlandish and unthinkable way at the time. When the album was released on 1 June 1967, in the midst of the “Summer of Love”, the world stood up and took notice, for better or worse (MacDonald, 1994).

Sgt. Pepper ushered in a turning point for the public perception of pop music. While other groups had released albums in 1966 utilizing a single, loose concept to frame the songs on the album, The Beatles brought this concept to the forefront of Western popular culture (MacDonald, 1994). By creating a concept for their album that allowed them to transcend their “mop top” image, the Beatles hoped to have their new studio creation tour for them (Martin & Pearson, 1994). The Sgt. Pepper concept would change the way the “pop album” was viewed by critics and listeners alike. The album would go on to influence countless artists, and was virtually responsible for the birth of the progressive rock genre, inspiring future groups of musicians to craft albums around different themes, stories or other guidelines (Moore, 1997).

Sgt. Pepper was something never before seen in music in 1967. The artwork and packaging alone was enough to make the record buyer consider taking a ‘trip’ with the Beatles, but the music on the vinyl record was something else entirely. For the first time on a Beatles record, every song seemed connected in some way, however small. It didn’t feel right to listen to just one song at a time; it felt right to listen to the whole album, front to back, every song.

By 1966, the group was not faring so well. The intense pace of their schedule and the rigors of Beatlemania had taken their toll on the band. Following a tour of the United States concluding on 29 August with a show at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, the group privately decided to stop performing live (Spitz, 2005). The group was already headed in the psychedelic direction of Pepper on 1966’s Revolver. Recorded throughout 1966, the album featured the group’s first uses of different studio techniques that would play an integral role in the recording of Sgt. Pepper (Martin et al., 1994).

The group, particularly Lennon and McCartney, also began experimenting with the sounds of avant-garde music, especially tape loops, reversed tapes and altered sounds achieved by altering the playback speed of the tapes. Inspired by avant-garde composers such as John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, The Beatles included heavy use of tape loops on Revolver (Spitz, 2005).

Utilizing new techniques and effects, the group began searching for ways to alter the sounds of conventional musical instruments. Studio engineer Geoff Emerick would play a vital role in the group’s discovery and application of new sounds. (Kehew et al., 2006). The sonic innovations and genre crossovers achieved by the group and the studio staff during the recording of Revolver set the tone for the rampant experimentalism that would take place during sessions for Sgt. Pepper.

Old Sounds, New Sounds

In terms of sonic diversity and experimentation with different forms and styles of music, The Beatles were already well versed. The group had experimented with eastern music, soul music and even classical (Greg Kot, personal interview by the author, 23 February 2009).

The Beatles had also been listening to a variety of different music throughout 1966 that would come to influence their psychedelic direction. McCartney would later recall in a 2004 interview: “But we were just doing our own thing. It wasn’t that we set out to make groundbreaking albums. The reason those records were so musically diverse was that we all had very diverse tastes” (McCartney, p.247, 2004).

The music of the underground scene, groups such as Pink Floyd, The Mothers of Invention, and AMM, and modern classical and experimental composers, such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, no doubt had a subtle influence on The Beatles’ recording sessions during this period (Heylin, 2007). Harrison’s introduction to Indian music and religion in 1965 had inspired him to purchase his own sitar and take lessons (Womack, 2007), and he was also growing personally, with a different outlook on life influenced by Indian culture and music (Spitz, 2005).

Lennon and McCartney both claimed the Beach Boys’ seminal 1966 album Pet Sounds as a great influence going into the studio to make Sgt. Pepper. According to MacDonald, McCartney himself confessed, “the Beatles would need to surpass anything they had done to equal it” (p.172, 1994). The Beach Boys weren’t the only artists from across the Atlantic the Fab Four were paying attention to; according to author and journalist Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune, The Beatles “were always listening” and were especially influenced by several of their American peers. They were also investigating other important albums released by American groups in 1966, including 5D by The Byrds, the debut album by Los Angeles psychedelic band Love and Bob Dylan’s masterpiece Blonde on Blonde (Greg Kot, personal interview by the author, 23 February 2009).