The connection is terrible, the hum and the crackle a memory of rotary phones and heavy receivers, of analog, slow time.

Hello, Shaun.

Hello, my friend, how are you?

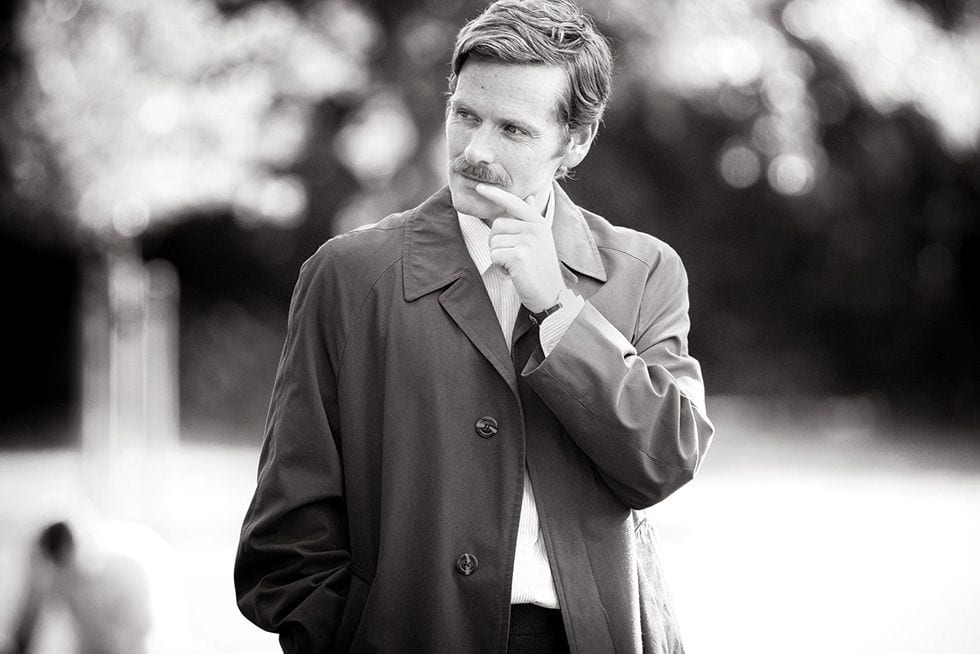

We’re with Shaun Evans, a British actor who plays the title role in ITV’s Endeavour series. Endeavour is a meticulously crafted, slightly subversive prequel to Inspector Morse (1987-2000), a beloved crime-drama series based on Colin Dexter’s detective novels of the same name.

By 2011, when Evans was recruited to play young Morse, he had been acting for over ten years, yet it’s Endeavour that proved to be his magnum opus – a defining work that not only allowed his acting talent to blossom, but also nurtured his natural storytelling ability. As the series progressed, Evans quickly earned the job of an associate producer and eventually got his wished-for moon: the opportunity to direct Endeavour. His is “Apollo”, the second of the four episodes of season six that airs on PBS this month.

Here Evans, a figure quite untypical for the high-profile television milieu, speaks of his creative process as both an actor and a director, of his (somewhat confusing) relationship with the character of DS Endeavour Morse, his earnest reluctance to live a celebrity’s life, and his aspirations as a storyteller, which include writing and photography as well as acting and directing. In conversation, he is mercurial, unafraid, reactive, and – though hospitable – an island.

[Note: The moustache, being a very obvious/drastic change in Endeavour’s appearance, seems to have hijacked 99% of popular discussion about season 6. Ever since the moustache appeared, Shaun had been asked about it in every single interview, without fail.]

This is not a question about the moustache…

One great thing about doing something long-form is that you can afford to change and open it up, you know? A person grows; nobody stays the same. So I think on a purely facile level it’s just something new. [laughs] It’s also something to do with Fancy’s death, and with becoming a person that you weren’t before.

A hair shirt of sorts? Self-punishment, no?

Yeah. Yeah, I think you’re right. That’s probably an element to that too, subconsciously.

You assumed parallel duties of acting and directing in season six of Endeavour; this was your first time directing yourself, too. Viewers, in general, tend to have a vague idea of what directing entails and how it’s spliced together with other filmmaking roles – those of a writer, producer, production designer, DP, etc. As a director, what is it, exactly, that you do?

Basically, you have a script – along with the rest of the team. Everything is a collaboration, no one works in isolation, even the writers don’t work in isolation, everything – when you’re doing stuff for TV or film – is a collaboration. As a director, ultimately you see the script, and as the script is being reviewed and then re-drafted, you have ideas on your take on the script, a sort of outside point of view, which can then be incorporated in further drafts as the story progresses. Before you begin shooting, you hopefully have a kind of overall view of the film that you want to create. You then make a decision about locations – again, like I said, this is not in isolation, it’s a part of collaborating – but you make decisions on both locations and on the choice of the cast and the guest artists and also on the costume.

You make all those decisions up front, run them by your team, and then you get to shooting: on each day you prepare where you’re going to shoot, what the action is that’s going to take place, how it’s going to take place and how you can cover the scene in-camera. Again, you do that as part of a collaboration with people working on the shop floor, the DP and camera operator and the actors.

When that’s finished, you assemble the material that you’ve shot and work in collaboration with the editor; you change scenes around, you change shots around. You have a fresh pair of eyes on what you have shot, to see if it’s still in accordance with decisions you had at the beginning, though very rarely is that the case: oftentimes, something new will happen and you’ll see a new avenue and follow that if it’s more interesting than the original idea. Of course, you then work with the editor, and with the executive producer at that stage as well.

After that, you work with the composer: you watch it – well, this is how I tend to do it – silently first and stop at points where you feel there should be music, or there should be something to either help the story along or to give it bit of a background to help tell the story from a sonic point of view. The composer then goes away and does his work, you sit and review it, and then – in this case we went to studio in Abbey Road where the Beatles recorded some albums! – we recorded it with the full orchestra. You put that on and you’re constantly tinkering again in collaboration with executive producers, and then you present it to the world and hope that people enjoy it. That’s the director’s point of view.

[Note: Evans directed the visually stunning “Apollo” that juxtaposes – painfully, in high relief and with use of puppets – humanity’s reach for the moon and that same humanity’s smaller passions, eventually prompting an ever-important question of which is the larger of two. Endeavour’s production design has always been impeccable, but in “Apollo” the environment is elevated to a language rather than just a well-crafted background. The effect is slightly, yet unsettlingly, surreal; one of its visual vehicles is the very dramatic use of red in the frame.]

As an example of your involvement – who is responsible for the reds in “Apollo”?

All the red colours? That’s part of your preparation; you’re trying different things out. Some directors work this way, some don’t. And that’s marvelous, that all works, but I think you have to take responsibility for the visual way you’re trying to tell a story, and that includes a colour palette, which will help you to tell the story in the way that is akin to the vision you had at the very beginning.

So, in our case, you work with the designers and say well, these are the colours that I like, this is the colour I think that should be, this is the atmosphere that I’m trying to create and I think that could be helped with this colour or that colour, you know? But then, each director gets to do that with his own film. It’s not set.

It seems that some of your scenes in Endeavour were self-directed well before you assumed the director’s role.

To be honest, I think if you’re a good actor, then you’re kind of directing the scene anyways, in your mind – or at least you’re directing the character that you’re playing: he would do this, I imagine I will come in from this entrance and I would say it in this way. Likewise, if you’re a good director, then you’ve acted out each of the scenes and each of the characters’ parts in your head anyway. So, I think, they go hand in hand.

I am always open to collaborating with the director that comes in. You want someone to tell you something: if you’re self-directing as an actor, in isolation, I think it’s kind of problematic. Just given the fact that the story is called “Endeavour” and I play, obviously, Endeavour, you have a strong sense – or, at least, I have a strong sense – of what’s important in each of the stories and what’s important in each of the scenes, where I’ve come from, where I’m going to, just really on a narrative level. So, of course, if I’ve done all that homework, it limits the options: you know what the scene’s about, you know the most efficient, the most interesting way to tell the story, and so you are kind of… oh, I don’t know, it’s tricky what I’m trying to say now. It’s not like you’re self-directing, but you do have a strong idea of something. Of course, I’m always open to another way of doing things, but I guess you have to come in with an idea yourself in order to then be blown away by someone else’s. That’d be easy though!

Do you ever argue with the director about, say, your vision of a scene?

Oh no, I never argue! Yeah, I will give my opinion, but I will always listen to their opinion as well. There shouldn’t be a hierarchy; one solution should always present itself and make sense. For example, someone says, “You should come in from here”, but it’s not compatible with the scene that you haven’t shot yet which you’re shooting in three weeks’ time, where you know that you’re coming from somewhere else, then it makes sense.

The director has an enormous amount of things to think about, and if you’re playing one part, then what you have to think about is different, and you think about it in a different way. A good director will allow actors – and every department, actually – the room to do their own work. There shouldn’t ever really be cause for argument. There should be always cause for discussion though. I think, argument is good in one sense, inasmuch as you can really wrestle with “is this the right thing, is that the right entrance, if that’s the right thing to be focusing on?” It’s good to have a discussion – sometimes a frank, robust discussion – about it, because then you come to the truth of it, you know? And that can only ever be a good thing. But there always must be dialogue. I never argue.

The episode that you directed [“Apollo”] though second in series 6, was shot first. Looking from the outside, the quality of your self-awareness as an actor has been slightly new ever since. How did directing change your view of yourself as an actor and of other actors?

I’ve been directing for three or four years now, and, I think, it’s not that you see yourself differently… as you grow, you understand the new way of doing things. But… yeah, I suppose it modifies [your outlook] and then, hopefully, your work evolves. My hope would be that your work as a storyteller evolves regardless of which hat you’re wearing, do you know what I mean? Then you do it in a more precise way, so perhaps. Perhaps that’s the case. Perhaps not as well, I don’t know. But I also think that it should be something that’s never visible.

Each of us is a cluster of information bits projected into the outside world. This is also true for fictional personalities, if they are articulated well enough. DS Endeavour Morse certainly is by now, thanks to Russell Lewis [Endeavour’s writer] and you. Is he a job, separate, well-controlled thing? Or would you say that his personality exerts influence on you now?

That’s a really good question! … What I would say is… [pause] Thank you, first and foremost, for the compliment. My goal has always been – since I started acting nearly 20 years ago – to make each of these lines on a page into a living breathing character that has hopes, and dreams, and fears, that people can then relate to. I see that as my task. And you do that by your imagination. I don’t believe in a sort of mystical – this is just me, personally – “being” you create which then can influence you. And, I suppose, this goes back to the question you asked me previously as well about [my] ambition as a storyteller.

The more you direct, the more you see the economy of a gesture. You become technically more proficient when you’re watching things; you just need to do one thing in order to tell that part of the story. I don’t need to create so much as an actor, I don’t need to do… oh, I’m not being very clear. Perhaps it’s not clear to me. Hang on for a second, let me just think about it. [ten seconds of s i l e n c e] You hope, as an actor – or I hope, as an actor – that you create the environment where you can do work that is believable and potentially inspired, right? So, you’re not thinking about it too much. You put your mind into a different place. What would I want to achieve in this, what would I… ? So your mind is occupied with something else.

You couldn’t allow… I mean, a character couldn’t come and… Oh, I don’t know what I’m saying. I’m just talking shit now. [laughs] I don’t know what I’m saying anymore. Maybe it’s not very clear to me. Yeah, perhaps it’s not very clear to me. I don’t really think about it too much, to be honest with you. [laughs] I don’t really think about it, I just do it!

Yeah, it always requires effort, without a doubt it being because we’re very different, d’you know what I mean? The character, the part and myself are very different. I suppose – going back to the moustache – it’s another manifestation that, at this point, it shouldn’t be too comfortable. If it becomes too comfortable, then it easily becomes boring, and it becomes boring for me. That’s why you have to keep pushing yourself and keep challenging yourself both as a director, as a producer, and as an actor as well. You have to, even if it’s not there in the writing.Fortunately for me, in this case, it is; but I’m involved with the story throughout the year so by the time it comes to shooting, things are in place and the story is advanced enough that it never feels like you’re playing a character. Eeeee, you’re playing yourself, you know? I feel like you should always be looking for the differences rather than similarity.

I’m not that interesting, bloody hell! This is a way more interesting character in a more interesting set of circumstances than myself, you know? And, I think, a good worker… [pause] I don’t really want to be seen. I want my work to be invisible. So you just crack on, you just believe the character, you just believe that that person’s there… I know you watch me on TV and whatnot, but I don’t really want people to see me. If that makes any kind of sense.

It does make sense, yeah. Even though, having watched you work, I would say there’s a little bit more of you in him now than it used to be… but I might be mistaken. You haven’t taken an acting job outside of Endeavour for four years now, and I think there were only *two since 2012, why?

Well, I know that’s because… I really love acting, I think it’s an amazing job, but I’ve begun to be interested in different ways of telling stories that didn’t involve me physically. As a result, I knew that I wanted to produce and direct more, and the only way to do that – I knew that ultimately wanted to direct an episode of Endeavour! – is to pay your due diligence and go and do work, so you learn your trade, you know? You’re going to keep learning your trade, so I purposefully created this… I was fortunate enough to be in a situation where, as soon as Endeavour finished, I could go and learn how to direct on a different show for the BBC, and I was afforded that opportunity.

It takes you a long time to learn and to get good at a thing, you know? You have to keep practicing and keep practicing, so I filled the time in between Endeavour with directing, which was an amazing experience. I think, like I said earlier, it’s the two sides of the same coin; if you learn to tell the story both as an actor, and a director… and a producer, then you are still telling a story. There’s something about it which just works for me. It felt like a natural evolution.

Don’t get me wrong, it’d be nice to play – I am kind of looking for something now, another part to play, but I do feel like time is precious and you ought to look for where and what is going to challenge you. After working all day every day – after what I think was 20 weeks or 30 weeks, or however long it takes to make Endeavour – I felt a bit exhausted… not exhausted, exactly, but I just felt, what would be the next thing, what would be challenging? I’ve just been acting for 12 hours a day on that job, for 20 weeks straight; what would challenge me and push me? So, I’m throwing myself into an environment which doesn’t make you feel comfortable, like directing. Directing other actors, learning how to speak to the crew, and how to set up shots and all that – I felt more scared by that, I felt more daunted by that, and I thought… whoa, these are the things that make you go and do that.

What’s your visual “home”, or homes, if any? A visual space that you feel an affinity with, perhaps, be it a movie, or a director’s style, or an artist’s vision that’s close to your heart?

Oh, that’s a good question. Again, look, I think inspiration is everywhere, and we’re all, each of us – whether we know it or not – completely influenced by so many things. There are a few directors [whose] work I admire greatly; likewise, there are a lot of writers [whose] work I admire greatly, and photographers. I suppose, for me personally, that’s always been…

The first time I ever had a job was in a camera shop! So I’ve always been incredibly interested in photography for two reasons, really. I think, when we talk about economy of storytelling, that could be the best way. If you can tell the story in one picture, or a selection of pictures, that is a sort of a precursor to the work that we do anyways, so when I prepare my work as a director – and sometimes as an actor as well, and occasionally as a producer – I always have a visual sort of template. I may be inspired by one particular photographer, but for whatever the job is, I bring hundreds of photographs,’cause that speaks to me more and it’s an easy way to articulate whatever it is you’re trying to create yourself. There’s hundreds, there’s really hundreds of photographers that I really like. Yeah – this, this, this, this, and this.

Speaking of photography, The Liverpool Art Book project has shared your contribution online recently; is this is the first time your artwork is being shown in public?

Yeah. This is going to change. But I’m kind of very private about that because I think, like I said earlier… I love photography and I love working, but prior – up to this point – I always felt like you have to keep a little bit of something for yourself, you know? And both photography and writing I really enjoy as my own pastime. Now I feel like I would like to make exhibitions and perhaps make a book.

That’s something I’m up for doing next, to make an exhibition and make a book of the prints that I’ve done. Or even just a little book, perhaps, of short stories… and maybe the photographs would be accompanied by short stories. The reason I want to do that is because everywhere I go I always have a camera with me, and always have a notebook and pen. There’s something very simple about it, about having that complete agency over your work as a storyteller.

I suppose, what I seek now after being in the middle of a big team of people for a long period of time – which is wonderful! – is just singularity and a bit of agency over what I do: this is the story that I want to tell in these words, and this is the story that I want to tell in these images, or, this is how I see this particular thing, you know? Just as me, just as a person. This is my take on that, this is an idea that I have – without having to turn it into a film or a TV show, or a play, or whatever. But just as an offering: there’s my offering, my take on this.

So, the Liverpool art book… Originally, they asked me for a quote. They sent me a couple of pages of the book and asked me – because I’m also from Liverpool – if I would be interested in making a quotation for it. And I said, yeah, cool, no worries, but sent them a selection of my photographs instead. Actually, I was in Liverpool a couple of weeks ago, so I just shared it with them and they were like – yeah, amazing, we’ll include this in the book, is it OK with you? So I thought well, it’s happened so swiftly and fortuitously that I should just embrace it, run with it, you know?

Wonderful. I would like to say that your photographs are particularly terrific.

Thank you so much. This is really really appreciated.

Oh, yeah. They’re wonderful. Wonderful.

Is there a special significance to the photograph that you contributed to the “Liverpool art book”?

There sort of is. I was thinking about the story that I was writing, a story about a soldier who returns to Liverpool and has a sort of connection to the river and water. I did it because Liverpool is my home; I don’t live there, but that’s the place that I go to when I need to just have a bit of time for myself, see my family. There’s something about returning to the source.

So my idea – or the thing that I was toying with – was the source of that particular river, its tributaries, and where it begins… I was doing a bunch of research into that and thinking how that would fit in with both how I see why Liverpool itself, as a place, is useful and important to me, and how it could be important to this character that I was thinking about having in the story. So I frequently went down to just see the river, and like I said, I always have a camera with me. So I was just compelled to take some pictures and then make something out of it, you know? It’s all just evolved; it was kind of like a sketchbook for the story I was writing, to be honest. [laughs]

What camera do you use for everyday shooting?

A Leica… It’s a film camera, I’ve got a Leica M3 and a Leica M6, both of which I always have on me. Both of them are film; one I tend to use more for black and white and one I use for colour, and then I develop them myself. Yeah, just a little Leica with a very simple lens. I don’t want to be bogged down with all the equipment and all the different lenses, I just think – get in and get out, you know? What camera do you use?

A Canon DSLR. Everything happens in post. I do love film, but the last time I developed a roll myself was when I was ten years old. Should, maybe, get back to that.

[laughs] Ah, but you do what works for you. Each has pros and cons, I think.

You are not using social media at all, but how is it with you and media in general? News, politics, popular TV shows, whatever else is current? It can, I suppose, get very loud – to the point where you have to shield yourself from it…

I’m kind of selective about what I choose to expose myself to in that regard, but I think it’s incredibly important. You can’t work in isolation, like I said, I feel like I’m always consistent about collaborating and talking about big and little things. It’s important to any storyteller to be a part of their time. As to me, I do do that, I’m very much abreast of current affairs. And the world interests me. I love being in the world. [laughs] I love being right here right now, that’s a part of telling stories, part of writing, part of photography, part of being an actor, part of being a director, it’s all about understanding the times, so yes, I do keep abreast of that.

I’ve sort of flirted with Instagram and Twitter and all that, but it’s probably only purely from a voyeuristic point of view. Like I said, what I’m interested in is for people to just enjoy the work. Whatever medium it takes, it’s good to just enjoy the work and perhaps get something out of it or perhaps not. But for me personally, it’s not a means to… it’s not for me to be… I’m not sure how to say this. I don’t need attention. [laughs] I would like my work to get attention, and of course there’s some degree of yourself that you have to put out there in order to facilitate that, to make it happen, but I’m not interested in letting people know about what I had for breakfast. I just choose to live that way. But I’m also very much a part – and that’s not answering your question, is it? – yeah, I know what’s going on in the world, I suppose is what I’m saying. I think that’s important.

Was there anything today, even if very small, that made you look, made your heart skip a beat, but you haven’t told anyone about it yet?

You know what, today, to be totally honest with you, has been a magnificent day. I got up super early, went into town with my camera to take a few pictures on my way to a talk that a photographer was doing… Susan Meiselas, she’s just won the – I don’t know how to pronounce it! – the Börse prize. I don’t know if she won it? Yeah, I think she won it. In any event, she was opening an exhibition and doing a talk this morning, so I went into town early to see that. And as I got into town, the light was just particularly incredible, it kind of was amazing.

Right after that, I went for a coffee – just to get a bit of breakfast ’cause it was, probably, 8am – and I was planning a trip. I’m going to go on a trip soon, and I was planning it in my notebook, and then [it turned out that] a guy at a counter lived there, at the place where I was going to go. And It was just beautiful too; I ended up asking him what it was like there and if he could give me any tips. It was one of those amazing mornings. Everything had a flow.

Oh, and there’s a stray question about “Apollo” that I wanted to ask. Last one – and a bit of a teaser for the American viewers who are yet to watch the new season. There is a scene with Joan Thursday in which DS Endeavour Morse goes completely outside of his character; we’ve never seen him like this, ever. What’s behind this?

As I said, everything is a part of a collaboration. That particular scene was written – and we shot it – two seasons ago. There’s something which happened in the story, and we shot it in a very different way (we were in a car). We shot it, but when it came to the crunch, it didn’t fit into the story. Everyone thought it was a little bit too bleak which, to be honest, I agreed with. And then it turned up again, almost verbatim, in my story.

I thought, maybe there has to have been enough water under the bridge between the two of them that it would warrant that level of aggression. So we shot it and then, in the edit, I toyed with having it in and, I then took it out to see if it would work without it, and it worked equally well without. I did feel like it would be nice to keep them moving on. Not everything needs to be explained. It’s good to surprise. Sometimes I surprise myself, we all surprise ourselves and we surprise each other, right? So, you know, why not?

” Are we good, my friend? Have to shoot,” says Evans but forgoes no courtesy as we pick up loose ends. He asks, among other things, about this year’s run of the project I’ve worked on that distributes an unofficial Endeavour calendar in lieu of donations to War Child. He helped by signing a few copies, which made for a spectacular increase in contributions. Fame – though an ill-fitting word in Evans’ case – at work, in the way that won’t damage a state of not being seen. His goodbye wishes are many and warm, as if to equip one for a long journey. Yep, we are good.

+++

*1. Sir Richard Worsley (Lady Seymour Worsley husband) in The Scandalous Lady W (Sheree Folkson, 2015), an 18th century drama detailing the scandalous life of Lady Seymour Worsley,based on Hallie Rubenhold’s book, The Scandalous Lady W: An Eighteenth-Century Tale of Sex, Scandal and Divorce.

2. Tom, a government official in War Book (Tom Harper, 2014), a drama depicting eight government officials act out their potential response and decisions in a simulated war game scenario in which escalation of nuclear threat between India and Pakistan leads to nuclear war and quite likely the end of the world.

Season 6 of Endeavour airs on PBS stateside mid-June. Season 7 – likely to be the series’ last – is set to begin filming in late summer.

Author’s Note

Having chanced upon Endeavour in early 2017, I became very intrigued by Evans’ performance and, as a photographer, felt compelled to study his process of character creation the best way I knew how – by taking pictures. Nina Kharchenko shared my curiosity; we began visiting the set of Endeavour in Oxford to photograph the filming two years ago. In the fall of 2018, an exhibition of our behind-the scenes photos ran at the Jam Factory in Oxford. The exhibition was titled “Endeavourneverland“, and we share the pictures on social media under the same name; we are, one might say, a tiny creative collective. The images for this article were taken during the filming of series 6 in August and October 2018.