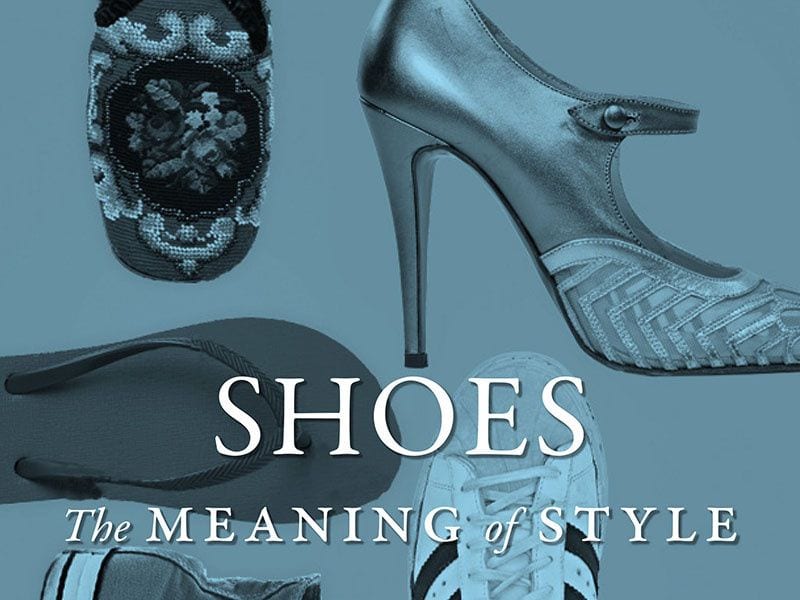

When you go to a really good museum, especially if it’s about a narrow or common subject, how do you describe what you have seen afterward? For those that can’t get to the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, Elizabeth Semmelhack’s book, Shoes: The Meaning of Style, will be the next best thing. Semmelhack is senior curator at the museum, and wow does she know how to make her subject engaging. Shoes is divided into four chapters: sandals, boots, high heels, and sneakers. Shoes are one of those things that everybody thinks they know something about. Because they’re on our feet, of course we do know something, and yet we really know nothing.

Before reading the book I had my own thoughts on what sandals or high heels mean. It turns out, to a large extent, a reader’s hunches about the arguments of this book will strike with relative accuracy. But while we have strong hunches about how to make meaning out of our footwear, we still struggle with calling up a lack of examples other than the ones that appear on our own feet—and the examples are the fun part. So while Semmelhack does indeed shine in the matter of analyzing these styles, her greatest gift is perhaps simply the plethora of examples she can offer readers beyond what they know from their own feet: the ridiculously expensive, the exceedingly rare or even one of a kind, the ancient artifacts, the modern art objects hardly meant to be worn at all, and then the Adidas or Manolos you see on the street but rendered here in an entirely new light.

Semmelhack gives a thorough history of these four styles of shoe, and the book is filled with textual examples as well as beautifully photographed samples from museum collections around the world. Each chapter is dedicated to one overarching idea that Semmelhack then traces through the history of that style. The sandals chapter is about eccentricity. Yes, hippies in Birkenstocks will make an appearance, but sandals as a display of eccentricity are centuries older than that stereotype. Same for the skinheads that appear in the chapter on boots—a chapter that ends up being about inclusivity instead of elitism, and this is where the author’s feminist chops really begin to stand out in the exercise of her analytical thinking. By the time Louboutins arrive in the high heels chapter, which focuses on the concept of instability, Semmelhack’s wit is also on display in such understated gems as: “Fashions that appear in men’s pornography tend to have longer staying power” (286).

I found the high heels chapters to be most surprising, perhaps because they never appear on my own feet or perhaps because I’d been locked into their iconic television personality from Sex and the City. Of course, this chapter confirms the reader’s suspicions about misogyny, but high heels actually belonged to men long before they were forced upon women, and the early history of high heels yields a number of amusing insights into how footwear becomes gendered and in what waves this gendering has come and gone over the centuries. The high heels chapter also begins a discussion about celebrity designers, and this continues into the chapter on sneakers, which takes the notion of exclusivity as its focus. The sneakers chapter opens onto celebrity athlete endorsements and is more manifestly about race than the other chapters, although issues of class have been highlighted throughout the book up to that point in a way that allows race to be a natural extension of a conversation already very much in progress.

In men’s fashion magazines, it’s said that one should dress from the shoes up. We all have some idea of what our shoes say about us, but we have very little sense of the history of those ideas. I found myself emotionally investing in and also reclaiming certain aspects of shoe culture that had come and gone from my life. For example, I’ve recently repurposed an old pair of Doc Martens that I wore in high school to use as bookends in my office. These are already fraught with meaning from all the trials I walked in them, but in digging through the boots chapter, I found even more cultural value in their historicity then I had simply intuited when I was younger.

Semmelhack’s book takes issues of identity politics firmly in hand, yet she writes like a true art historian. The result is an incredibly edifying, deeply entertaining, manifestly readable look inside everyday objects that most of us are too busy to truly consider. The book is a more than adequate reference guide for those in the industry, a sample of how to properly curate and discuss a museum exhibit, a lovely coffee table book, and a highly readable adventure in general. This is one of those rare books that truly offers something substantive for everyone who might not usually think about picking it up. On its face, such a daily subject may not seem worth getting excited about, but Shoes is not at all prosaic and it’s quite difficult to put down after the first few pages.

Men’s platform-sole boot (Reaktion Books)