“The word ‘Showa’ is heavy with suffering and despair…”

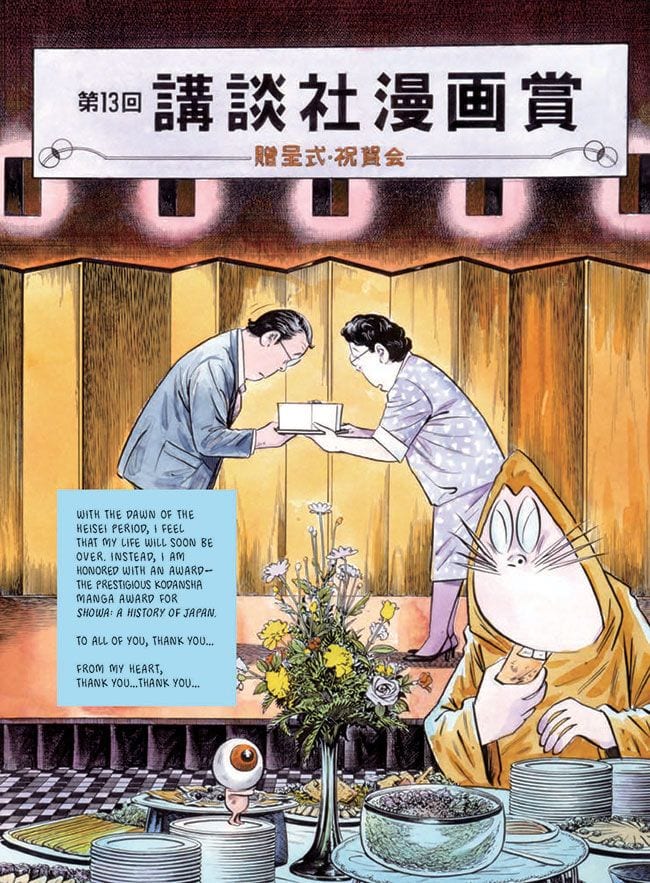

Thus Shigeru Mizuki reflects on the end of the ‘Showa’ era, that period encapsulating the reign (1926 — 1989) of the Japanese emperor known to the western world as Hirohito. The 63-year period has been synthesized in Mizuki’s epic manga Showa: A History of Japan, published originally in Japan between 1988-89, and now finally translated into English by Zack Davisson and published in a four-volume series by Drawn and Quarterly.

The final Volume 4, spanning most of Japan’s post-war history (1953-1989), was published in English just months before the death of Mizuki at the age of 93. Mizuki’s passing was marked with tributes from around the world, his accomplishments lauded not only in the field of manga but also in the realm of folklore (his research brought him international accolades and membership in the Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology) and peace activism. The Showa series, like much of his other work, is focused on reminding society of the evils of war and militarism. Having witnessed the rise of militarism in Japan, and having been drafted himself into several years of horrific fighting in the Pacific during World War II, Mizuki waged a lifelong struggle against militarism and war, not only through his own comics but also challenging other writers and comics artists who glorified war and militant patriotism in their own works.

The final volume of the series — which concludes with the death of the Emperor in 1989 and some final reflections from Mizuki on the lessons and meanings of the era — suggests Mizuki did not blame the Emperor for the horrors of World War II. He’s disparaging of the elites who stood by and did nothing while Japanese society lurched into the deadly path forged by its military, yet it’s the systemic nature of militarism that he targets. “We fought in the emperor’s name and in the emperor’s name we were slaughtered and disfigured,” he writes. “But I couldn’t be angry at the emperor. He meant nothing to me. It was the system I was forced into that I hated. War is so much bigger than one person…” It’s an insight he also argues passionately in his recently translated manga biography of Hitler: it’s systems and institutions, moreso than individuals, that are the true monsters.

An Era Ends

Volume 4 reads, on one level, as more of a straightforward history than the other books, much of it narrated by Nezumi Otoko, one of the yokai demon characters Mizuki made famous in his series GeGeGe no Kitaro. With the previous three volumes, Mizuki’s personal trajectory into and then through the horrors of World War II offers the reader a particular narrative to follow. Will he be drafted? Will he survive the war? (obviously, he did) How will he — and his family and friends — survive the horrors of the war? His own remarkable adventures absorb the reader’s attention, and the series situates itself in the extensive genre of historical manga depicting experiences of World War II (and the war in Asia which preceded it, stoking Japan’s descent into militarism and empire).

Volume 4 is something different: a 46-year span covering what many consider the golden age of post-war capitalism. Consequently, by virtue of the sheer amount of time it spans, it forms a unique volume. Western readers might not think of the ‘golden age’ of capitalism as a fertile backdrop for comics and manga, but in fact the political tensions and social alienation produced during this period generated many of manga’s masterpieces: from Osama Tezuki’s Ayako epic, for instance, to the shorter dark urban sketches of Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

Much of Showa Volume 4 reads as more of a historical text, with “rat man” Nezumi Otoko narrating key global and national events. Indeed, Mizuki intended his series to educate Japanese youth; he worried they were growing up without a clear understanding of the important 20th century history that shaped today’s world. He packs an astonishing array of events into the book, many of them rarely spoken of today even though they struck the country with intense effect at the time. These events span a wide gamut: from pop culture moments like the arrival of rockabilly and rise of theme parks, to political turmoil such as the storming of Japan’s legislature by student protestors and the struggle to oppose construction of Narita Airport. There’s whimsical commentary on music and film, and explorations of corporate scandal, murder and crime. It’s a remarkable, year-by-year memory ride through the country’s post-war history.

Its usefulness as a history text aside, there’s another important dimension to Volume 4. It’s the story of a man persevering against the odds in his determination to survive. Today, Mizuki is considered one of the greatest creative forces in 20th century Japan (and indeed, the world). But as he makes clear in the autobiographical moments of this volume, that was not always the case. As student protests rage and the Tokyo Olympics showcase a Japan resurgent, Mizuki struggles to put food on the table. He sells his wife’s kimonos to feed the struggling couple; bankers foreclose on his house, he can’t sell his comics and is unable to even buy a sweet bun or coffee in the market. While Japan shines on the world stage, he remains a struggling, ignored artist into his forties.

Part of the problem lay with the in-between phase of the creative medium in which he was working. The long-popular kamishibai medium (storytelling using illustrated storyboards) had become obsolete, and the manga which took its place had not yet crystallized as a commercially viable medium. Brilliantly creative writers and artists abandoned the field right and left, since it offered little commercial reward and even less indication of a future.

But Mizuki persevered. Driven to desperation by the need to support his wife and newborn child, the artist who in previous volumes depicted himself as a cheerfully lazy dilettante youth now becomes a frenzied writer of comics, so focused on his creative work that sometimes he can’t tell manga fantasy from reality.

The obsessive dedication pays off. In 1966 he receives a visit from the Kodansha publishers, who’ve noticed his work, and offer him a broad commission.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

As the volume alternates between world events and Mizuki’s own day-to-day existence, he offers fascinating and sometimes humorous glimpses into life as a (finally!) successful manga artist. He has to hire assistants in order to keep up with the deadlines and growing workload, and chronicles their sometimes rocky and often quirky relationship with affectionate mirth. At the same time, he offers a whirlwind tour of Japanese post-war history from his own personal perspective, a sort of annotated history lesson where he (and his army of yokai narrators) inevitably get the last say on politicians and cultural trends alike.

The closing of the era offers the opportunity to reflect on Japan’s present trajectory as well, and on the lessons of his own lifetime. Increasingly, as success surrounds him he finds himself plagued by the question of happiness. Although materially successful and finally able to not worry about starving to death (one of his recurring nightmares, and a very real threat during much of his life), he finds himself unable to enjoy success, and his reverie turns at times dark. “Manga… it’s a hard business. Success had taken me out of my long life of poverty, but I wasn’t able to relax and enjoy it. I had seven assistants and my family depending on me,” he writes, after he starts receiving a steady stream of contracts.

The work becomes so stressful he sometimes finds it difficult to discern reality from fantasy. Even his dreams, wandering the afterlife with ghosts and demons, reveal his struggle over the question of happiness. “There’s little peace in the physical world – the needs of your body and soul are in constant struggle. You have to find something to make life worthwhile…that’s not easy. I thought I could escape my hardships drawing comics. But then comics became what I wanted to escape from.”

On Being Not Unhappy

As the years pass and his fame grows, his studio becomes a magnet for fans and children of all ages, but it simply intensifies his own self-doubt, and what he sees in the now-prosperous Japan around him doesn’t inspire confidence either. “Everyone had their own troubles. I didn’t see many happy people — being not unhappy was about the best you could hope for. And for me, that meant hard work and lots of it. Sometimes groups of fans would come into my studio. Almost sixty years old and I still had to bow to the whims of children. I wondered why…”

In another chapter, a trip to the dentist reveals he needs dentures. “I didn’t realize I’d gotten so old!” he exclaims.

“Your life’s more than half over,” his wife reminds him.

“Hmmm… looking back, it wasn’t such a happy one,” he concludes.

His aged parents then chime in for a frame: “That’s our line!” says his father. “True. I’ve never even been overseas,” adds his mother.

The juxtaposition is a telling and important one. His parents lived during the tumult of the pre-war era and the dehumanizing poverty of World War II and its aftermath. Yet even the peace, technological advancement and economic prosperity of Mizuki’s contemporary Japan hasn’t solved the problem of individual and social happiness. In fact, in some ways Japan’s capitalistic and materialistic excess has replicated the social alienation of its early and mid-20th century militarism. In his concluding reflections, he reminds us that Japan’s early 20th century poverty led to militarism, and the glorification of collective sacrifice: ‘There is no individual, only the country!’ proclaimed the country’s military leaders. (“But it was individuals who received those death sentences called draft notes,” he writes in response. “We were supposed to be proud to die for our country. Scattered across the world — for a country that cared nothing for us.”)

The result was Japan’s defeat and the imposition of democracy — “a certain kind of freedom, maybe” as he describes it. Yet that “certain kind of freedom” (or at least the capitalism that accompanied it) has undermined happiness and led to another alienating form of collective sacrifice, one in which “It seems like companies are benefiting more than individual workers. The average office worker slaves away to pay his bills. Is that happiness?… Japan’s drive for success and efficiency has commoditized humanity. We are uniform and disposable again.”

The Lessons of the Past

It isn’t all dark pathos. In Volume 4, Mizuki does eventually find a sort of happiness. He reunites with his surviving war comrades, and eventually returns to the South Pacific island of Rabaul where he spent much of the war. It was there he lost his arm and suffered immensely, but he was also taken in by a local indigenous village that nursed him back to health. This was a life-changing experience for him as well (he almost settled there instead of returning to Japan after the war), and the village becomes a second home and important sanctuary later in life. His trips become more frequent as he rekindles his relationship with the villagers, and he finds in the simplicity of their lifestyle – despite its material poverty – the type of happiness Japan seems to be losing amid all its material wealth.

He also discovers the things that truly matter to him. “What they call the ‘golden years,’ they’re really the best years of your life,” he reflects. “When you’re young, desire and ambition consume you. As you get older… those things don’t mean so much anymore. As a young man, there was so much I couldn’t see, so much about life I didn’t even notice. I thought the most ridiculous things were so important. It’s like at sixty years old, my eyes are finally open. I never thought getting old would be this great.”

And so he turns his focus to the human relationships that matter to him, and to the folkloric research on yokai that consumes his intellectual passions. But the ghosts and demons of his manga continue to visit him, reminding him of his looming mortality (the conclusion of the series sounds like Mizuki is preparing for his own death as well, even though he was to live on for more than another quarter century after its publication).

There’s a wry element to Mizuki’s take on Japan’s social and political history. The broad sweep of Showa allows him to reveal the complexity of politics in a way that transcends the typical casting of history. Over the years and decades, Japan’s supposed saviours cast themselves in various guises – military dictators, democratic politicians, conservative elites and radical socialist activists. Invariably, they all turn out to be equally inept or equally corrupt. The lesson is not a nihilistic one, but a moral challenge to the reader: to ensure that “the sickness of abundance” doesn’t lead us astray from the universal solidarity of humanity — “a treasure money can’t buy”. It’s also a reminder to do the things that make you happy, and not to be sidetracked by ambition, fame, or material wealth. Mizuki, who experienced grinding poverty and prestigious fame and success alike, sifts through the implications of both in this collection.

Showa

Presenting World War II and its aftermath from the perspective of the ‘defeated’ nation offers another important vantage. In the west, it’s all too common for those memorializing the war to honour the military as the ones who ‘protected our freedom.’ Mizuki’s work offers a different lesson: it was militarism that led the world, not to safety, but to disaster in the first place. Armies and soldiers do not protect freedoms, but are the greatest threat and menace to our freedoms, no matter whose side they purport to be on.

Mizuki and Nezumi Otoko join together for an emphatic conclusion: “It’s necessary to learn from the past, to not repeat the same mistakes. And to never forget it was real! This actually happened to us! I can never forget the war. Never forget what happens when the military rules a country… Never forget the price that was paid for the world you live in now. Never forget the lessons of history. It’s up to you. Don’t make the same mistake again!!!”