In the introduction to Chinese Movie Magazines: From Charlie Chaplin to Chairman Mao, 1921-1951 Paul Fonoroff describes how he started to collect old film magazines while on a research grant in Beijing at a time after the Cultural Revolution, when old magazines started popping up at second-hand shops and stalls. What he has uncovered is not just a collection of rare ephemera from the world of Chinese movie fandom, but a history of the Chinese film industry, film market, and the post-Imperial era to the early years of the People’s Republic of China.This collection, from which Fonoroff has now created and written this book, is now housed at the C.V. Starr East Asian Library at the University of California Berkeley. Chinese Move Magazines stands as a beautiful art book, a tactile history book, and important English-language history of early Chinese cinema.

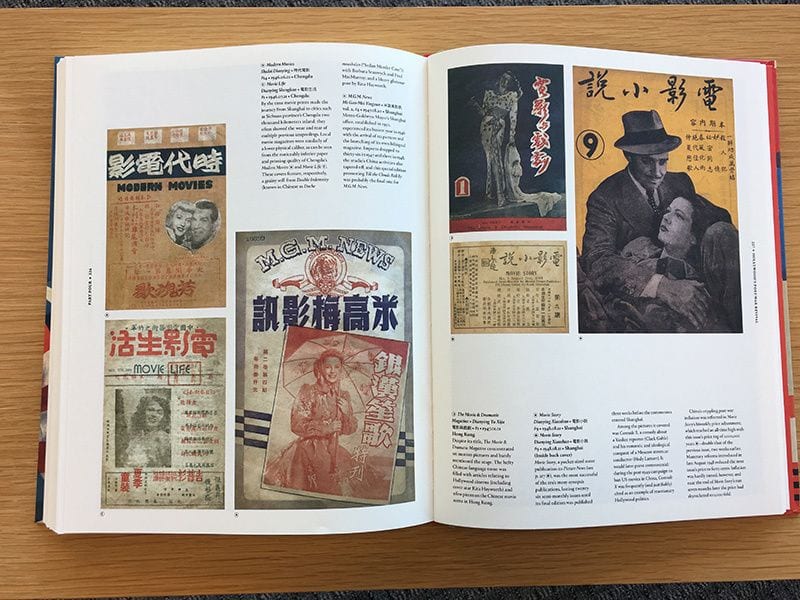

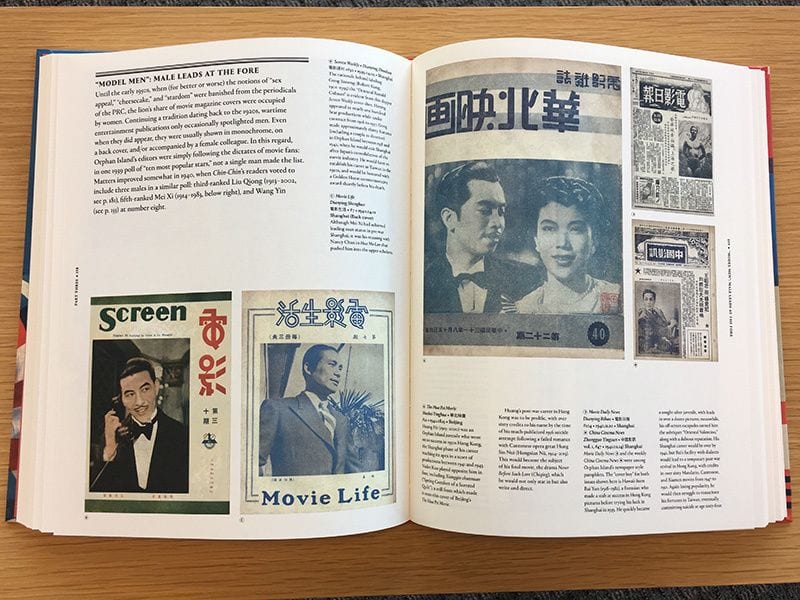

The work is displayed in four parts based on historical eras, with each part broken down into two- to four-page spreads devoted to specific topics, with images primarily drawn from the front and back covers of the magazines. (Over 500 covers from 300 magazines are included in the book.) The layers of information contained within these images and sections explore graphic design, celebrity photography and influences from Western filmmakers; namely how Hollywood and international film distribution accessed and interacted with the Chinese film market, printing techniques, trends in Chinese film genres, and competing political pressures placed on the industry.

The sheer amount of often obscure content requires some scholarly context, and I was at first irritated by Fonoroff’s brief, one-page introduction. But this is the rare art book where not only should every image be pored over, but every caption diligently read, and it’s in the captions that the content takes shape. What at first may seem like bits of trivia about the covers and magazines, then weave and build into each other, packing unexpected emotional heft. Starlets rise from obscurity (and some never much out of obscurity) only to die and disappear from drug addiction, war, or fall victim to the purges of the Cultural Revolution. The film industry centers itself in Shanghai then drifts south to Hong Kong as the Japanese encroach in the Second Sino-Japanese War, while regional industries pop up in Beijing and Manchukuo. The publishing industry for movie magazines follows them, tracking the trends and shifting sociopolitical environments.

Fonoroff’s ability to capture decades of history, an epic novel’s worth of story, and succinct tragedy is conveyed in this caption of a cover for Movietone/Diansheng magazine cover from 1937: “A member of Shanghai’s left-wing movie scene at age fifteen, Sun Weishi was billed as Li Lin during her brief career as screen ingénue in 1936 and 1937. That chapter of her life came to an end when the Japanese invaded Shanghai on 13 August 1937 — coincidentally also the date of her appearance on what would be the last Movietone cover before the magazine’s war-related closure. A foster daughter of Zhou Enlai (1898-1976), Sun would be sent to the Soviet Union for further studies, returning to China for a productive stage career as director, writer, and translator before her persecution and death in prison during the Cultural Revolution, a fate shared by Jin Shan’s first wife Wang Ying (see p.64).”

Through all matter of historical strife film magazines, hundreds of them, keep sprouting up, some eventually shuttering due to lack of sales, some due to the impossibility of the publishers’ situations. Still, the magazines come to represent some resiliency of spirit, the smiling faces of movie stars representing a persistent need and desire for movies as art and escapism and sometimes as a way to push allegorical political messages, from leftist and Communist politics to veiled anti-Japanese commentary. In Chinese Movie Magazines Fonoroff highlights the capacity for humans to embed their desires and history in the most innocuous-seeming of creative efforts, and the power that can lie within a discarded pile of papers at a second-hand shop.