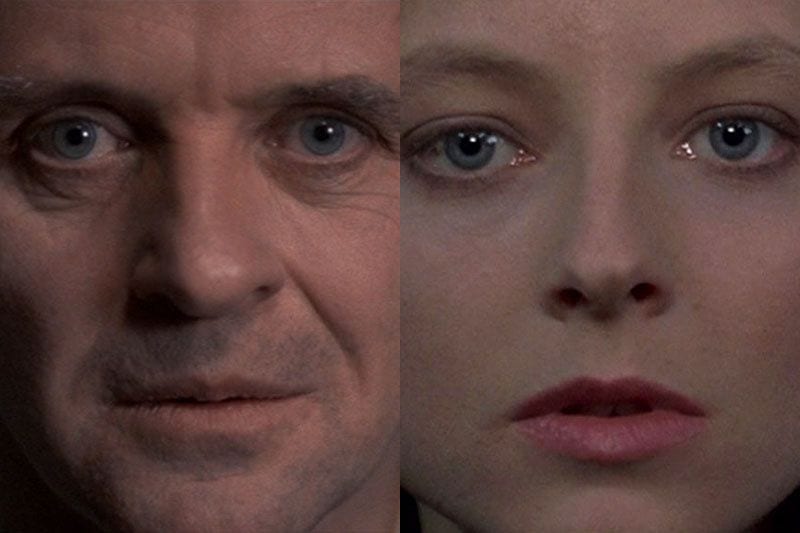

Of all the words of caution Jack Crawford could give Clarice Starling, “You don’t want Hannibal Lecter inside your head” isn’t a particularly generous warning. After all, there is no “how” to that advice. The Quantico agent-in-training must figure it out for herself, and, of course, there would be no The Silence of the Lambs if Starling followed Crawford’s guidelines. Jodie Foster’s Clarice allows Anthony Hopkins’ Dr. Lecter into her psyche, and so too have nearly three decades of rapt viewers. Part of the twisted catharsis derived from Jonathan Demme’s 1991 classic comes from submitting to Lecter’s aura from a just-safe distance. Now 27 years after its release, the prisoner on the other side of the fiberglass — the gentleman cannibal with his sketching of the Duomo and his penchant for a nice chianti — rules the imagination.

Yet what’s stirringly prioritized on this year’s Criterion Collection re-release is not the dive into brutal masculine psyches that define so much serial killer fiction. No, the story’s definition stems from its physical, stomach-turning detective work—and more importantly, the tenacity of the woman doing it. Hannibal Lecter is the movie’s icon. Clarice Starling is the movie.

It’s hardly a hot take to claim Starling is important to The Silence of the Lambs. She’s the protagonist of the film. The title owes its name to an unshakeable symbol of her early-life trauma. Jodie Foster won an Oscar for the role. But long after people forget about Billy Crystal wearing Hannibal Lecter’s ghastly muzzle at those same Academy Awards, Clarice Starling will still be endowing this film with its resolution, the sense of humanity and resolve that relegates its many sequels and imitators to a lower-class of storytelling. The trials of a young woman battling the varied but equally poisonous sexism of Quantico’s halls and West Virginia’s squad cars continue to age better and better. (I’d bet on any number of think-pieces to this effect when the film turns 30 in a few years.) Nobody knew better that Silence of the Lambs is a movie about a woman navigating the coded, malicious passageways of a man’s world than Jonathan Demme.

Emphasizing the late director’s admiration for Starling is the centerpiece of this Criterion edition. Foster provides the foreword to its Blu-ray companion booklet, wishing the new version “infuses all the emotion [Demme] intended.” The same booklet contains a 1991 Film Comment interview with Demme in which he claims initial revulsion at the idea of making a movie about serial killers but changed his tune when he found he could deliver on a garish, exploitative genre via a heroine’s quest. The Blu-ray’s audio commentary goes even further to unpack the ways Demme and cinematographer Tak Fujimoto collaborated in their hyper-intimate, direct-to-camera style to inflect Starling’s singular position of discovery and development in the story.

To reflect on Foster’s performance as Starling is to peel back the layers of a character who is simultaneously peeling back and regenerating her own layers. There’s a deep sense of purpose driving all her ambiguity. She must unpack precisely that which cuts and scars her. She must treat the monsters of both prison cells and FBI offices with utility if she’s to become anything more than the tragic ideal of her small-town sheriff father, an uncomplicated do-gooder gunned down by fate.

As a performer, Foster radiates intelligence and vulnerability in a rare combination for the detective genre. There’s no jadedness, wit, or liquor to numb her when her adversaries brazenly test her concept of self. Lecter attacks what little pride a rookie has when he observes that Starling is “not more than one generation away from poor, white trash.” You’re not worthy of the success all the test scores and performance reviews say you are, he bitingly implies. In response to what we now know was Hopkins serendipitously mocking her attempt at an Appalachian accent, Foster performs shame and resilience happening on two levels. Between actors and characters, a young professional stares back at a tormenter knowing that, through all this, she needs him.

In Starling, Foster renders a protagonist so driven and retentive that she may feel inscrutable to a viewer looking mostly for entertainment. In a recent episode of his Rewatchables podcast, host Bill Simmons professes Foster’s performance is perhaps his only problem with a movie he otherwise cherishes, though he can’t quite explain why. Simmons says he’d vastly prefer Michelle Pfeiffer in the role and goes on to wonder if Julia Roberts could’ve played the part. Alternate castings like these suggest a desire for a less dimensional hero, and maybe, in that way, a more likable one. Pfeiffer and Roberts undoubtedly would’ve played Starling with a more visible edge, more overt sexuality, and the kind of well-meaning defiance we recognize in movies like Erin Brockovich or Dangerous Minds as “spunk”. Such characters repel macho and bureaucratic crap because they are self-assured. Starling, meanwhile, is in a state of becoming, a state in which likability, cool, or even a consistent personality, aren’t nearly of the same importance as protecting the vulnerable by any means necessary.

She evolves the way any classic detective would—through work. Let’s return to Jack Crawford once again, played with effortless, withdrawn guile by Scott Glenn. On its face, his manipulation of Starling is for her femininity. He means to arouse Lecter sexually on the path to gaining insight on the film’s serial killer at large, Buffalo Bill. But in practice, Starling becomes an agent of Crawford’s dirty work, a veritable intern accomplishing out of drive what the boss no longer has the guts for. Maybe he never did.

In the West Virginia autopsy scene Foster cites as the film’s true inflection point for her character, Crawford stands aside while the trainee records observations about a waterlogged corpse. She details the indignities wrought upon the body with her face just a finger length from rubbery, brutalized skin. She notices the glitter of the woman’s fingernail polish and recites the horror of the wounds she sees. If this is the moment at which Starling is finally putting everything she’s learned into practice, she hasn’t become Hannibal Lecter or Jack Crawford; she’s become herself.

In that scene and many others, the sensory textures Starling encounters in her investigating are the products of studied, novelistic filmmaking. The Criterion edition quotes Silence of the Lambs author Thomas Harris as opining, “To write a novel, you begin with what you can see and then you add what came before and what came after.” In other words, work from the immediate, outward. The same principle holds true for police work, one deduces. It’s precisely how Starling reasons her way backward into catching Buffalo Bill: “We covet what we see everyday.”

The tactile highlights of the movie are many — a scalpel dissecting a moth pupa, possibly the loudest zipper in autopsy-scene history, a sewing needle piercing human leather — but there are less repulsive details that reveal what no crime writer musing on human nature could. Take the army helmet collecting dust upon Buffalo Bill’s basement shelf and the miniature American flag propped against it. Such a brief image tell us just as much about this assailant as his 30-foot, concrete pit: America the violent, steeped in conquest, dwelling deep within his home. It’s these tangibilities that ground The Silence of the Lambs, depicting Starling’s bravery and Buffalo Bill’s madness through briefly seen objects.

Without the same care for symbols, countless pieces of entertainment have extrapolated from The Silence of the Lambs in other ways. Of late, Netflix’s Mindhunter positions the nebbish, Jack Crawford type as its protagonist and the birth of criminal profiling as its journey. David Fincher’s series tells a circuitous, meditative history about when G-men put down their sidearms and formed a bridge between cops and psychiatrists. These characters would agree there’s something to be learned from the Hannibal Lecters of the real world and go digging for their grotesque monologues. They stare into the darkest abyss of the human condition and see how, or whether, it stares back.

The larger true crime obsession, from podcasts to prestige televisions shows, hinges on much the same theme. Nearly three decades after The Silence of the Lambs released, we have an entire subgenre of entertainment founded on morbid curiosity and the implicit question, “What kind of person could do this?” There is no end to such content because there are no firm answers to such a question. Life generates horror, entertainment re-stages it, and we willfully leave the doors to our minds ajar for boogeymen long dead or somewhere behind fiberglass to enter.

The heinously real and the intellectually terrifying may well live together in The Silence of the Lambs. But it endures as the peak of its genre because — staring contest with the abyss be damned — some things can be solved by the professional who’s perpetually growing. She’ll pursue all leads, into her cocoon and out again.