A new DVD release of an “Archers” film promises something like a long dormant dream. The joining of writer/directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger seem less like a professional venture than an artistic calling. The Britain-based filmmakers’ 1948 masterwork, The Red Shoes, bravely looked beyond the stylistic perimeters of the contemporary cinema, as the film finds subtlety in its visual extravagance.

While this Technicolor entry’s ballet performances call for a broad scope, the stylized realism makes The Red Shoes play like a fairly tale, intimately told and fondly remembered. Its trademark dance sequences show a refined expressionism, with every flourishing dance move echoing a range of moods. The human yearning behind a performer’s ambitions appears in vivid detail.

As innovative as their work was, the filmmaking team eventually parted. Powell eventually made Peeping Tom, a dark vision of a serial killer for which the viewing public certainly wasn’t ready. The protagonist’s obsession with victims as they face death leads him to scientifically study them – his chilling motives became disturbingly rational, and filmgoers were repulsed by the sheer credibility of this character. Hitchcock’s Psycho, which appeared in America a year later, rationalized its killer’s motivations, yet distanced his madness from viewers to leave him an object for our critical gaze. Hitchcock’s masterwork helped to revolutionize cinema, while Powell’s groundbreaking blend of art and terror cut short a career at its most innovative moment.

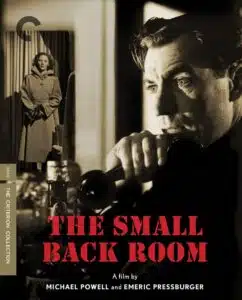

Thus, we must look backward to find other the great moments of his career. After the splendid The Red Shoes, Powell and Pressburger opted to make a smaller, quieter movie, in which they would experiment further with subtle characterization. The Small Back Room (1949) looks to the hushed goings-on in military intelligence. The Archers were intrigued by the nuance of Nigel Balchin’s novel of the same name, in which the professional pressures of a WWII bomb-diffusing expert leak into his personal life. The Archers had plentiful material to work with here, room for style to flourish in every set piece.

The Archers’ The Small Back Room sports a stylized realism with touches of expressionism. The interplay between the two styles is so controlled that the film hardly seems deliberate, but something like an automatic filmmaking exercise. With sustained precision and detail, we feel the hands of the Archers molding every minute of the running time without the stiffness one would expect.

Even the side players take shape in minimal screen time, and the setting – wartime London – takes on characterization with limited outdoor footage. Much of The Small Back Room would suggest a docudrama’s verity if the film’s style weren’t so refined.The Small Back Room makes the mainstream cinema of the period seem overwrought and heavy-handed, and the budding Italian neorealism like the outtakes of an experimental workshop. The unification of multiple dead-on elements in The Small Back Room creates an effect of je ne sais quoi, a pure example of the elusive auteurist élan described by critic Andrew Sarris.

The expressionistic tones come and go, leaving shadowy hues in the black-and-white camerawork. Yet the sustained control breaks during a surreal scene a la Spellbound, when bomb expert Sammy Rice (David Farrar, looking like a hardened Cary Grant) is attacked by a looming clock and booze bottle – the alcoholism theme gone ham-fisted. This moment comes when pressure is high, as if the Archers didn’t trust that we can sense it. It’s surely felt by Susan (Kathleen Bryon), Sammy’s suffering girlfriend, who takes the brunt of his frustration and is an onlooker to it as a secretary at his office.

When Sammy learns that booby-trapped bombs have injured children, The Small Back Room flirts with high concept developments, though a plot-driven twist never shows. Powell and Pressburger want to present an intimate experience behind high-scale sensationalism. Yet the clarity and economy of style highlight the film’s underwhelming core that cannot realize dramatic satisfaction. The Small Back Room plays so calculatedly and deliberate that it seems unsympathetic to its audience’s interest, as if the filmmakers are too concerned with their character to consider making him relatable to the audience. Through the Archers’ gaze we watch closely, but are never let in. This objective study to perfection remains a cold exercise, well deserving its minor status in the Archers’ oeuvre.

Though with plentiful extras, even a lesser release from the Criterion Collection is a treat. This edition of Small Black Room includes a full body of background material, as usual in even the single-disc sets from Criterion. A conversational commentary track by scholar Charles Barr avoids a stuffy tone common in scripted analysis. This type of informed scholarship accompanies viewing well, as it sounds lively and not detrimental to the film’s rhythm.

In a new video interview, the Archers’ jolly cinematographer Chris Challis is critical enough of the honored filmmaking team to remain objective and not celebratory. More curious background comes in audio dictations by Powell for his biography, and in a new essay by critic Nick James. While the latter provides a strong context, it struggles to assert the value of what is essentially a low point for the filmmakers. By repeatedly describing the film as a “noir”, and even invoking Raymond Chandler, James wrong-headedly attempts to broaden the scope of a film with minimal merits to offer.