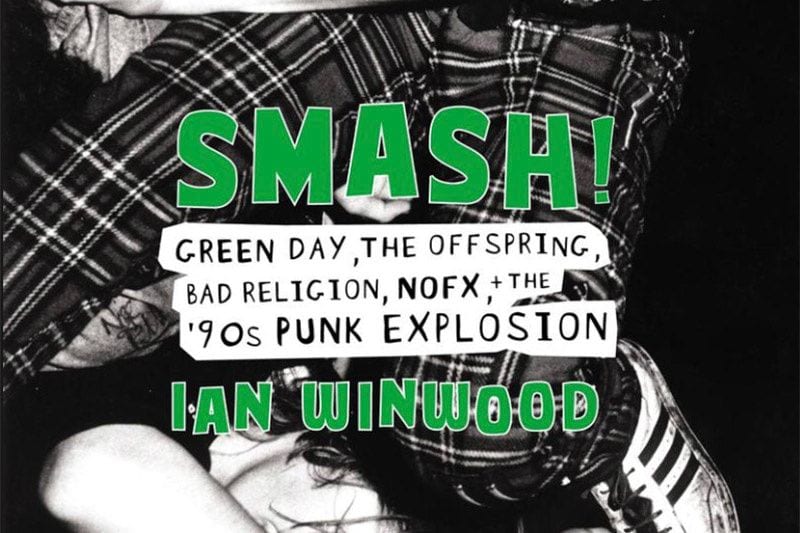

In 2011, a Facebook group (not currently available) inspired by a series of “Big 4” tours featuring the biggest stars of ’80s thrash metal bands garnered some media attention by insisting that Green Day, The Offspring, Bad Religion, and Rancid should tour together as “The Big 4 of ’90s Punk Rock”. Naturally, this led to discussion among fans who argued whether or not these were punk’s most popular and/or influential bands. So it’s not surprising that over a decade later, music journalist Ian Winwood has written a book, Smash!: Green Day, The Offspring, Bad Religion, NOFX, + the ’90s Punk Explosion that purports to be “a group biography” about these same bands, and how they (somewhat inadvertently) took a genre of music that had always been controversial, maligned, and only enjoyed by a relatively small group of people, and turned it into a commercial success that gained international pop culture prominence.

Unlike traditional biographies or oral histories, Smash! seems pieced together from various viewpoints and timelines. This makes following the text a little difficult for readers, as a chronological order of events is largely abandoned in favor of spiking interest or proving a point (such as the introduction, which starts with a detailed account of Green Day’s notorious Woodstock performance in 1994 before circling back to the author’s stated purpose of the book). Modern punk rock purists will likely be unhappy that Winwood has reduced the genres’ forefathers in the ’70s and ’80s to a handful of blurbs that downplay their successes, but his main point is that punk wasn’t considered a major part of pop culture until its artists reached multi-platinum album sales and sold-out arena tours. The first few chapters go on to explain that, unlike today — when virtually every genre of music has millions of international fans that keep it in some kind of popular spotlight accessible to the mainstream — in the ’80s, punk rock music was not only unpopular in the mainstream, but also considered a hindrance to the financial success of any musician who attempted to play it.

Smash! gives several perspectives as to why this was the case. In the mid-’80s, most punk groups found themselves either disbanding or switching to genres that were more popular at the time, like glam rock or heavy metal. The argument is made that musical trends come and go, and often what starts as an inspired new idea quickly becomes copied to the point of blandness. Therefore, the author, in a way befitting of a music journalist, has strong opinions about what songs and albums are better than others and states these biases as if they were proven facts. Whether you find this jarring plot or amusing often depends upon how much you agree with him. He praises the debuts of other early punk groups, like Fear and Circle Jerks, but condemns their subsequent releases for lacking the same wit and technical prowess.

Where the book truly is in its stories of what kept punk rock alive: the dedication of ordinary people who made seemingly insignificant steps to promote the music they liked and ended up making a major difference. For example, Chrissie Yiannou attends a NOFX show without even knowing what the band sounds like but becomes so impressed by their music that she organizes and self-promotes another, bigger show in the UK using only a telephone, a fax machine, and the contact information listed in various fanzines. Not only are her efforts successful, but she eventually become the UK publicist for every act on Epitaph Records.

Winwood quotes several other musicians and industry figures in describing punk rock as a movement of sorts, one that appealed not only to young people who were poverty-stricken and/or had come from broken families, but their middle to upper-class suburbanite counterparts who longed to reject and differentiate themselves from mainstream society. Ironically, the idea of being outside of the realm of the mainstream appealed to an ever-increasing fanbase that caused this music to become wildly popular with the general public. Many flocked to punk rock concerts, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that merely attending these shows was often dangerous, due to the casual vandalism and various fights that broke out in cramped venues. (In a particularly memorable passage, Dexter Holland of The Offspring describes hiding under a table as a teen at a Dead Kennedys show that was cleared out by police who motivated the crowd to disperse with tear gas and nightsticks.)

Therefore, a significant portion of the book is devoted to the resulting controversies over the backlash that happens when something that is infamous for being unpopular, becomes popular. Green Day signs on to Warner Brothers and has to deal with taunts and accusations of being a “sellout” from fellow musicians and dirt-throwing concert-goers, yet goes multi-platinum with Dookie, the fifth best-selling album of 1994. The Offspring signs with Columbia Records, but keeps their punk image intact by declining offers to appear on Saturday Night Live and The Late Show With David Letterman. Other bands like Rancid and NOFX turn down very generous deals from major record labels in favor of creative control and loyalty to others.

Winwood does a good job of presenting this conflict from both sides by pointing out that both The Sex Pistols and The Clash were signed to major labels, yet suggesting that many punk groups wouldn’t fare well on large record labels that were concerned with a conventional public image. Still, the book’s hero seems to be former Bad Religion guitarist Brett Gurewitz, who starts Epitaph, a small, independent record label for punk rock bands. When a major record label offers to buy half of his company for over $50 million, he turns it down as a matter of principle and takes out a second mortgage on his house in order to press out more records. His efforts lead to fame, fortune, and major label deals for Bad Religion and The Offspring.

Many similar books revel in gossipy tales about the bad behavior and excesses exhibited by its subjects, and while there are some excerpts about ruined hotel rooms and various drug and alcohol abuses, Smash! gives a refreshing twist on this typecast with the message that punk music actually saved or prevented some of its creators from destroying themselves. In the book’s most inspiring passage, producer Rob Cavallo inserts an e-mail address in the liner notes of Green Day’s Dookie and receives hundreds of messages from fans who thank the group’s music for pulling them out of suicidal depression.

Still, Smash! has many faults. Anyone looking for a complete biography of the bands will be sorely disappointed, as the author completely ignores many major events in a group’s history in favor of focusing on relatively minuscule anecdotes. For example, there’s a detailed, elaborate description of the origins of the tooth extraction footage featured in Green Day’s “Geek Stink Breath” music video, yet there;s no mention of any of their albums or work after 2004. Winwood also has a way of heavily criticizing the moral faults of other genres of music (such as the disturbing homophobia expressed in various rock and rap songs in the late ’80s), while glossing over the occasional tastelessness of some punk groups (a passage in which Leftover Crack puts out an EP entitled “Shoot the Kids At School” not long after the Columbine tragedy is presented in the positive light of non-censorship by independent labels.)

The final pages contain a reprinted article from 2003, in which the author plays pool with members of the Offspring. While it would have been better if Smash! closed with a summary of the present or a taste of the future of its genre, perhaps it’s best to describe this book as more of a patchwork quilt of sorts, with good bits here and there and some pointless filler leading to an abrupt ending. Ironically, that makes the book itself very punk.