Though the Western is the only genre uniquely set in the United States, its presence in US fiction, despite the recent big screen insurgence (e.g., True Grit, There Will Be Blood, The Revenant and more) has dwindled since its 20th century peak. Only a handful of 21st century films, TV shows, or novels depict the late 19th century period of colonial expansion across the so-called frontier. But the West—or at least a fantastical version of it—continues to expand in France, where Laos-born writer Loo Hui Phang and acclaimed bande dessinée artist Frederik Peeters published The Smell of Starving Boys in 2016. London’s Self Made Hero released the first English version this winter.

Phang imagines a privately funded propaganda campaign into the “Comancharia” for the purpose of photographing the landscape and attracting settlers who will then mine its mineral riches. But one member of the expedition adds, “I’d have loved to believe in something impossible,” a desire seemingly shared by the authors. Though the post-Civil War setting is nominally historical, Phang’s characters quickly shift from the unusual to the fantastical: a gay photographer whose fake spiritualist photos turn real; a cross-dressing teen who speaks the secret language of horses; a cadaverous-looking bounty hunter who sucks horses dry of blood. Even the pot-bellied, colonial capitalist stops wearing pants and envisions founding a utopian civilization free of women and sexuality. A tribe of Comanche populates the periphery of the plot, with an unnamed old man following the explorers and silently delivering tokens of apparent magic: a double-exposed horse head on a photographic portrait plate, a severed horse head that serves as a soul-summoning bull-horn to herds of stampeding horses.

Oscar, who has fled sexual scandal in Manhattan, wears an aristocratic boy’s portrait inside his locket. Peeters renders Milton, the party’s farmhand servant, with nearly identical features, substituting a white wig for cropped blonde curls. Milton, however, is no boy, but a virginal young woman named Weather fleeing a father trying to sell her into marriage. Oscar, apparently transformed by her boyish looks and the whimsical West, falls in love. The two have sex for the first time while her father’s zombie-like bounty hunter searches outside their secret cavern chalk-marked with magic runes by the old man.

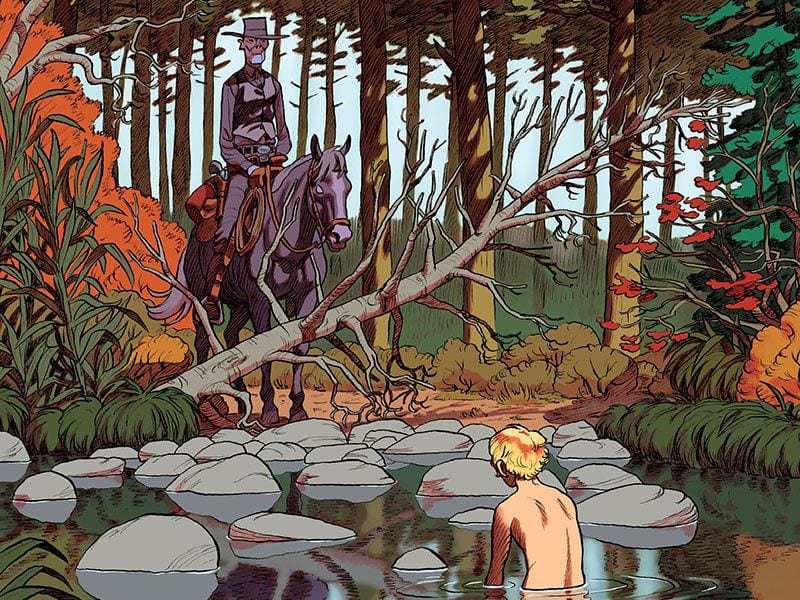

Peeters renders Phang’s world in a consistent, loosely naturalistic style, with the occasional cartoonish feature reserved for the racist capitalist, the caricature of Phang’s social critique. Peeters’ layouts are similarly consistent and feature a four-row base with one to three panels per row. His vertical gutters occasionally align but typically avoid rigid grids in favor of shifting patterns, including a dozen sub-columns in which the novel’s reading path briefly moves top-to-bottom rather than left-to-right. When the effect is achieved through combined panels, the image content tends to be panoramic, with expansive vertical views of the western landscapes.

(courtesy of Abrams Books)

When Peeters divides a panel into thinner, horizontal strips, the content is accordingly cropped, usually of facial close-ups reduced to eyes or mouth. Panels are almost invariably rectangular, with the exceptions appearing near the novel’s end and coinciding with moments of violence: an arrow through a neck, a bullet into a gut. Peeters abandons his base layout for the four-page climax, including the novel’s only two-page spread and full-page bleeds. The striking visual shift evokes the simultaneous splintering of the story’s reality as physical and seemingly spiritual worlds collide. When Peeters reprises the base layout for the epilogue, the world is stable again but permanently altered as Weather and Oscar ride off into their ambiguous afterlife together.

The contributions of Edward Gauvin, the French translator, are even more ambiguous. It’s unknowable whether Phang’s original French included the equivalent of the clichés “in the blink of an eye” or “There’s the welcoming committee.” Since such phrases cluster in the dialogue of the expedition leader, the most two-dimensional and satirically broad character, the effect mostly works. But when Oscar’s speech includes the novel’s title, the intent is less clear. While giving oral sex to Weather, Oscar reminisces about the sexual delights of boys: “if you only knew the smell of starving boys … I’ve never felt that way about girls … But you. Goddamn. You awaken it.” Oscar presumably means “starving” to be erotic, perhaps intending something closer to “skinny” or even “emaciated”, but “starving” has a more distressing connotation. If he actually finds starving boys arousing, then he’s turned on by a sex partner’s desperation for food, which then implies domination and coercion. Though I doubt that was Phang’s intended meaning, it’s equally difficult to believe she and Gauvin would not have worked through the semantic nuances of the novel’s title.

I also wonder about the amount of nudity of the novel’s only female character. Phang and Peeters find multiple opportunities to strip Weather of her clothes: a bath in a stream, a sex scene, an order at gun point, another sex scene. While Oscar is sometimes naked, and Peeters draws the capitalist’s mushroom of a penis more than once too, the eye of the novel roams longest on Weather’s adolescent body, including on the cover. The Western frontier, as romanticized by the French authors, is largely a sexual frontier, a border between genders and sexualities—what the story’s moralistic villain would eliminate. While it’s difficult not to root for the romance, it’s unclear why a female body, even a female body briefly understood to be a male body, should receive greater attention. It’s also unclear why the lone and unnamed native character should care about, let alone magically aid, Oscar and Weather’s romance, especially given the threat that their expedition poses. As her name implies, is Weather close to nature and so, as the cliché goes, like an Indian?

Despite these questions, the graphic novel’s mix of fantasy and Western tropes is involving, and Peeters renders Phang’s story with subtle craft. Phang also emphasizes the nature of image-making from the first panel: an upside landscape as viewed through the inverting lens of Oscar’s camera. The authors repeat the motif twice more, including on the novel’s final page, reminding readers that The Smell of Starving Boys is itself a set of inverted images too, ones that alter as much as reveal their subject matter.