The idea that photographs hand us an objective piece of reality, that they by themselves provide us with the truth, is an idea that has been with us since the beginnings of photography. But photographs are neither true nor false in and of themselves. They are only true or false with respect to statements that we make about them or the questions that we might ask of them.

I have a bad feeling about this place.

— Letter home, Spc. Sabrina Harman

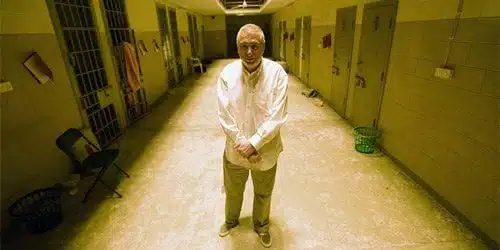

“I was in the mess hall,” says Spc. Jamal Davis, “And I looked up and I saw myself and Dan Rather.” It was 2004 and the Abu Ghraib photographs were all over CBS. Davis, then a guard at the prison and now appearing in Errol Morris’ new documentary, Standard Operating Procedure, remembers the pictures’ effects — the shock, the outrage, and the anger that greeted their release and changed Davis’ life forever.

Morris’ film reconsiders the photos in multiple contexts, provided by interviews with prison guards, Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, and Brent Pack, Special Agent for the Army’s Criminal Investigations Division. Assigned to analyze the photos taken by several young soldiers in order to figure out exactly what happened and when, Pack ensures that the film is not just about the crimes or participants, the “atmosphere” at Abu Ghraib or the responsibility of the military officers and civilian officials who were never charged. While these questions are surely compelling, the movie is more deliberately and (for lack of a better term) more poetically invested in how the crimes were defined by images. “In all my years as a cop,” he says, “half of my cases were solved because the criminal did something stupid. The photographs were that something stupid.”

As the film demonstrates, that something stupid” became evidence of a set of crimes the perpetrators didn’t quite comprehend. As Lynndie England puts it, on arriving at the prison, she and other newbies were struck by the cruelty of what they saw and what they were told to do, namely, to “soften up” prisoners for interrogations. “We thought it was unusual and weird and wrong,” she says, “But the example was already set.” England’s image is among the first to appear in SOP, the notorious shot of her with the prisoner the guards called “Gus” on a leash. On screen for a few seconds, the photo dissolves into pixels, underscoring the many countless contexts and pieces it assumes. Circulating in media space, the photo assigned England the doubled status of “pixie” and “monster,” the sign of U.S. devolution and corruption, but also, separate and contained, the most notorious “bad apple” who defines the good norm.

“People said that I dragged him,” says England, “but I never did.” Now, her hair is longer, her face is fuller, and she has a son, Carter, by Spc. Charles A. Graner, Jr. (himself court-martialed and convicted of prisoner abuse and currently married to Megan Ambuhl, like England, a guard at Abu Ghraib and interviewee in SOP). Still, England appears oddly detached, even unaware of what she means in the culture that so badly needs her to mean something. “When I was in the brig,” she reports, “Every woman was there because of a man. You enter the military, it’s a man’s world. They’re gonna try to control you.” She adds, concerning the prisoners, “We didn’t kill ’em. We didn’t cut their heads off. We didn’t shoot ’em. We didn’t make ’em bleed to death. We did what we were told, soften ’em up.”

Her seeming lack of perspective becomes a perspective. As the prison population at Abu Ghraib grew exponentially (Karpinski says, “Nobody had a plan for how you release a formerly suspected terrorist. The order was, you’re not to release anybody”), the crowded conditions and lack of supervision made for chaos; the soldiers did what they were told and repeated what they saw. “Did any of this seem weird?” Morris asks Ambuhl, his voice echoing from off-screen. “Not when you take into account that we’re helping to save lives,” she says evenly, her recollections throughout the film underscoring her loyalty to her husband and the “cause.” While some soldiers recall felling discomfort at the time (Davis says, “For hours and hours, all you hear is screaming”), other interviewees echo Ambuhl’s view, that they were doing what needed to be done, what they were told, what they understood to be right. As SOP shows, the perspectives from inside Abu Ghraib were fundamentally different from those generated by the release of the photos.

The fact that some guards took pictures, kept records, seems the most telling aspect of their increasingly inexplicable behavior, though it remains unclear exactly what it tells: “I started taking photos,” says Spc. Sabrina Harman. Reading from a letter she wrote home at the time, she continues, “Not many people know this shit goes on. The only reason I want to be there is to get the pictures and prove that the U.S. is not what they think. But I don’t know if I can take it mentally. What if it was me in their shoes?” Harman’s effort at empathy, refracted in her frankly remarkable documentation, is recontextualized again in SOP. The images of Abu Ghraib include shots of Harman posing with a dead prisoner, smiling while giving a thumbs-up sign (she explains it as a nervous reaction, not knowing how to pose for such a photo and so resorting to poses she learned as a child).

This photo raises questions concerning prisoners died at Abu Ghraib, who was responsible and how the very idea of responsibility became dependent on the photos-as-evidence. Former military-police sergeant Tony Diaz remembers holding one prisoner’s arms while other guards beat him to death: “I think I got the blood on my uniform. It kinda felt bad. I’m not part of this, but you kind of are, ’cause you’re there.” But Harman, who appears in an image with the dead “ghost detainee” (unlisted in prison records, “He wasn’t supposed to be there”), was charged with destruction of evidence, because she moved a bandage to arrange the photo pose: this charge was dropped, though she was convicted of other abuses.

The film notes the illogic of such legalisms (and especially the fact that only enlisted soldiers were even charged with wrongdoing). It also makes the point that the illogic is premised on the photos, the fact that no officers were blamed for what went wrong has to do with what was visible, what was documented — and had nothing to do with context or framing, how the behaviors or the pictures were produced. (It’s lost here that Army Major General Geoffrey D. Miller arrived at the prison in August 2003 and recommended “Gitmo-izing” the system in order to gain “intelligence” from prisoners.) “The pictures,” says Ambuhl, “only show you a fraction of a second. You don’t see forward, you don’t see behind, you don’t see outside the frame.”

This collapse of limited vision onto missing time pervades the film. Though Pack carefully arranges the images derived from multiple cameras to form a remarkable timeline of ignorance, self-delusion, and multiple fears, you don’t see how it happened and the stunning policy-making that determined that sequence. The pictures from Abu Ghraib tell an incomplete story. As Harman imagines an alternative life, some small part of that omitted story comes into focus: “If I could back all the way up, I wouldn’t have joined the military. It’s just not worth it.”