The life of a non-performing pop songwriter for hire is probably more tedious than we realize. Unlike the singer-songwriter, whose story had been told to death in too many forms, the journey of the songwriter from anonymously and ceaselessly churning out material to eventually getting attached to a superstar is few and far between. Think of the teams: Comden and Greene, Goffin and King, Bacharach and David, Leiber and Stoller. Think of the solo songwriters: Cole Porter, David Foster, and George M. Cohan. These are only a few of the many who can be found in The Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. Some live in cities like Nashville, Austin, or Los Angeles, writing songs of romance, adventure, scores for films or commercial jingles to sell aspirin, cereal, and general pain relievers.

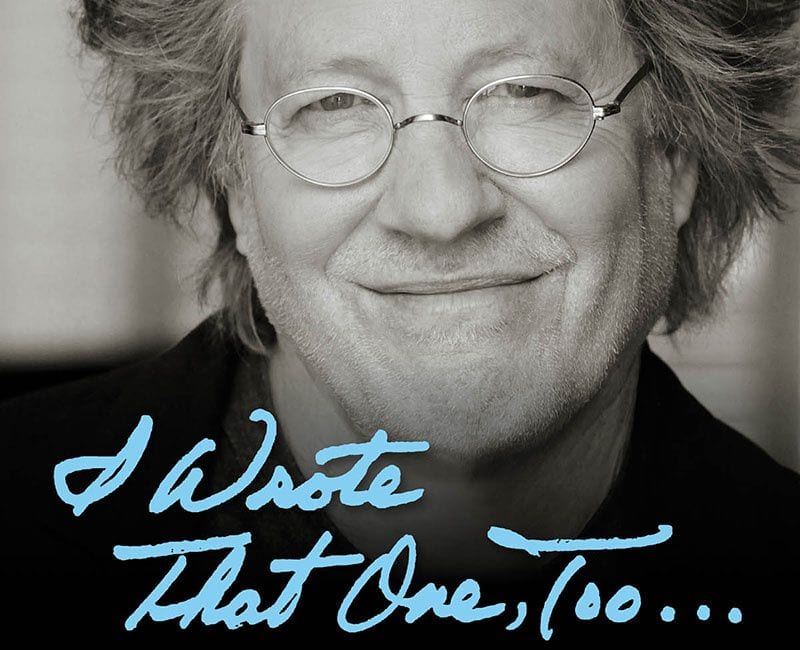

In his new memoir I Wrote That One Too: A Life In Songwriting From Willie to Whitney, Steve Dorff and his co-writer Collette Freedman have the difficult task of corralling a lifetime of experiences and impressions, and it doesn’t always coalesce. Admittedly, Dorff’s career has been filled with highlights. He’s scored films for Clint Eastwood, produced film songs featuring (respectively) Fats Domino, Ringo Starr, and many others. He’s been in the studio to produce a duet featuring Jermaine Jackson and a then virtual unknown named Whitney Houston. He wrote and produced the theme to the show Growing Pains; his theme to the hit TV show Murphy Brown featured the a capella group Take 6 and set the tone for the Motown-fixated character. With all that to support it, where could this book go wrong?

The problem with memoirs is that those who are behind putting together the narrative (and Dorff notes early on that his story will not be told in chronological fashion) have to fight the obvious risk of writing an extended awards banquet thank you speech. This, however, is what we get with most every encounter here. The chapter about Ringo Starr is giddy with fanboy enthusiasm: “My God, this was one of the Beatles!” Of the late actor Michael Landon, with whom Dorff collaborated on one of his last projects, we meet a man with “…great tan, long hair, and a youthful smile.” Of Dolly Parton, Dorff writes “She is one of the sweetest, most genuine superstars I have ever met.”

Indeed, the hagiography here get become exhausting and predictable. Dorff’s story is more interesting when he writes about music industry moguls like Herb Bernstein, Bill Lowery, and Snuff Garrett. It was through Garrett that Dorff worked with Los Angeles’s legendary session musicians “The Wrecking Crew” on a session for TV star Jim Nabors. (For some unexplained reason he refers to them as “infamous”, which seems a little unfair and misleading.) The “Knocking On Doors 3” chapter seems a little catty and implicitly homophobic in recalling a meeting with the late TV talk show host Merv Griffin, who had started his career as a big band singer. Dorff writes:

“Merv had two young gentlemen working for him, and they offered us food, drinks, and pot. Merv was in a casual sweat suit. Suddenly, this was all starting to feel a bit strange, and I adjusted my wedding ring to make sure everyone could see it clearly.”

Fortunately, the cohesiveness of the narrative, this meeting led to the entrance of Clint Eastwood in Dorff’s life. They collaborated on the country-music focused films Any Which Way You Can, Bronco Billy, Pink Cadillac, and Honkytonk Man. The reader gets the feeling that Dorff mourns the loss of those times, that musical style. He enjoyed three years of writing music for the Boston-based Robert Urich TV series Spenser: For Hire. The music was comfortable, non-threatening, a typical TV detective/cop show for the time 1985-1988. When the time came for the spin-off series starring Avery Brooks, A Man Called Hawk, Dorff assumed he’d stay on. He was wrong:

“I told Avery how much I enjoyed ‘Spenser for Hire,’ and how I would love to continue… [he responded] ‘There is a universe in which Hawk lives musically, of which I am not sure you understand.’… This was getting a bit too deep.”

That’s really the problem with I Wrote That One Too — Dorff and Freedman seem to have an aversion to depth. This is fine in the form of the pop song and the regular TV score, which requires producing a lot of material without putting as much thought into its meaning, but depth and purpose really needs to be a staple of the memoir. What does it mean? What did the memoir writer learn?

The other problems here are factual errors and inconsistencies. In Chapter 30, “From Charles Manson to Fats Domino”, Dorff recalls a moment when he was visited by FBI agents. His name had been on a list of those who had been threatened by Charles Manson. History tells us that Manson, a failed Los Angeles hippie songwriter who had sent tapes to many producers and music industry insiders, eventually targeted the house of Terry Melcher. Sharon Tate as there, and the rest is well known. The problem is that Dorff describes his reactions to the FBI agents like so:

“At first I thought they were two dudes trying to impersonate the Blues Brothers…”

The only problem is that Manson was happening in the late ’60s. The Blues Brothers, staples of classic Saturday Night Live episodes, did not surface until approximately ten years later. It’s this jumbled, sliced, piecemeal manner of telling a story that proves frustrating. Where are we going here? What’s the timeline? Sometimes a rambled nature of storytelling in a memoir is exciting. Sometimes it’s evasive, like padding a book for a requisite amount of pages and really not coming up with much in the end.

The life and times of Steven Dorff have definitely been filled with exciting moments and heartbreak. In the end, we read that his son Andrew (who had written the foreword dated 10 November 2016) died in an accident on 19 December 2016. It’s a tough but touching moment. Alas, the stories of divorce and heartbreak and professional bitterness and recriminations seem out of place with the gushing salutes to the likes of Barbara Streisand, Andy Williams, Jim Nabors, and Clint Eastwood. The scene of talking with Burt Reynolds, sans toupee, seems to have been included only for cheap shot humor. I Wrote That One Too can be at times an interesting account from a well-connected songwriter who knows how to write verses and choruses, but the bridges linking the reader from from here to there are, at times, unsteady.