Steve Johnson and Greg Oliver have been the unofficial oral historians of professional wrestling for the past 30 years. They’ve spent the better part of their adult lives cataloging stories from a group of professional athletes overlooked by traditional sportswriters and researchers. They’re part of the very, very small group of journalists and fans tracking down not just the wrestlers who may have been household names in particular areas, but journeymen performers who eked out livings on undercard matches. If the wrestler is deceased, they will often scour the internet looking for family members to share personal stories and fill-in missing details.

Johnson and Oliver have been writing together since 2004. Both are trained journalists, Oliver with the Toronto Sun and Johnson with multiple newspapers in Virginia. They have published five books together on wrestling’s history that pull from their extensive collection of first-hand accounts of life as a professional wrestler. Their most recent, The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Storytellers (From the Terrible Turk to Twitter), functions like an anthology of the best, most revealing, stories they’ve collected. Johnson estimates that they conducted well over 100 interviews to gather the material in this book. Neither will even venture a guess at the total number of interviews they’ve conducted over the past 20 years.

As a result of their relentless digging, The Storytellers is filled with one-of-a-kind accounts of the carnival scenery in and around the wrestling ring. It’s a celebration of the strange magic behind professional wrestling matches; how the performers engage audiences both in and out of the ring. It’s also a reflection on how professional wrestling has changed, and how elements of it have remained stubbornly the same, over the last 150 years.

Professional wrestlers have tended to live what Oliver describes as a “vagabond lifestyle”. A career in wrestling has traditionally meant traveling to whichever town had a promoter willing to pay you to perform that evening. Some would dress in devil outfits, or wear capes, crowns, monocles and berets, and adopt outrageous pseudonyms meant to excite fans. Others wrestled bears and alligators. They endured broken bones, assaults from spectators, and the general dangers of life on the road, just to play a role in the alternative universe of pro wrestling.

little blue robot by vinsky2002 (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

One wrestler Johnson and Oliver interviewed, Ronald Barriault, was a four foot, seven inch Canadian performer who renamed himself Frenchy Lamont. Barriault left home in 1961 at the age of 15 to train as a wrestler. He would go on to wrestle for 48 years. You can almost hear the strain in his voice as he tells the authors, “If it hadn’t been for my legs messing up on me, I’d still be doing it.”

Another, named Jake Milliman, recalls a conversation where a friend jokingly asked him, “‘If I was to propose to you that there’s two hundred dollars sitting down in Kansas City, would you drive down and get it and drive back?’ Well, hell, no, I wouldn’t. But you’re not only driving down there, you’re getting beat up! That’ll put it in perspective how much fun we had.”

“By and large the wrestlers are fairly normal even though they do an abnormal job,” says Oliver. “What sets them apart, though, is they were never censored. I’ve written about hockey, and those guys often had people holding their hand. They had PR agents and general managers and coaches making sure they got from town to town, and wrestlers never had any of that. They’ve had no supervision and that comes through in what they like to talk about. Hockey players, in general would be a lot more protective and hold things back. Wrestlers don’t think like that. They just tell you the story. That can be a lot more entertaining, for sure.”

Central to the appeal of a professional wrestling match is the ability of performers to create storylines; storylines within the course of a match, storylines over the course of several matches, storylines over the course of several years. Wrestlers tell stories with their bodies and their mouths. The best have equal agility in the ring and on the microphone.

“Wrestling is a sport, there should be no question about that in anybody’s mind,” says Johnson. “And every sport has a storyline that announcers usually try to tap into at the beginning to carry your interest through. But once the game starts, the storyline is secondary and you’re focused on the action, you’re focused on what’s happening. In wrestling, it’s essential that the storyline be carried all the way through the action. That’s the thread that has to be woven through the entire match. And athletes in other sports aren’t obligated to do that, which makes them much less interesting than wrestlers, in my opinion.”

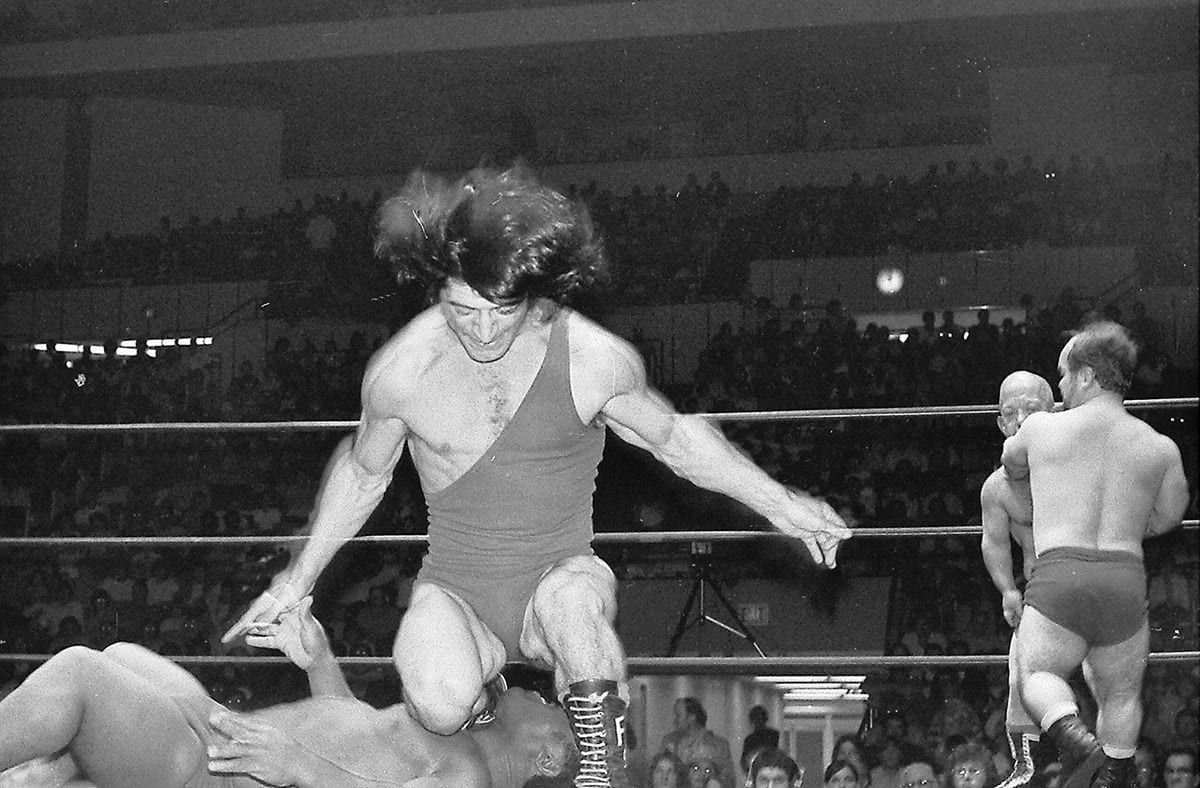

Frenchy Lamont. Photo by Dave Drason Burzynski (courtesy of ECW Press)

The book is wide-ranging, accommodating a history of both Yusuf Ismail, who caused a sensation in Manhattan in 1898 wrestling as “The Terrible Turk”, as well as Michelle Cooper, a contemporary performer who wrestles as Jewells Malone. Ismail participated in multiple matches that ended in near riots, risking his life in front of a Madison Square Garden crowd that shouted, “Kill the Turk! Tear him limb from limb!” Fans packed Manhattan’s Metropolitan Opera House for Ismail’s next match, attracted, as sportswriter A.J. Liebling wrote, by “the prospect of bloodshed.”

Malone’s life isn’t in danger because of rioting audiences, however. Instead, she performs in what are known as death matches; horrific affairs that incorporate fluorescent light tubes, thumbtacks, and nails. Her post-match routine often involves pulling pieces of broken glass from her skin. “When I’m working with barbed wire,” she tells Johnson and Oliver, “it’s good to have a second hand because that stuff can be pretty tricky.”

Jeff Walton, who worked in professional wrestling in Los Angeles, recounts promoting appearances by Dr. Sam Sheppard. Sheppard was the Ohio physician jailed for murdering his wife in 1954. Sheppard maintained his innocence, blaming the murder on a mysterious stranger. His story went on to inspire the television series and film The Fugitive. He turned to professional wrestling after his release from prison, appearing in several cities during his brief, chaotic stint in the ring. “He was a free man,” Walton tells Johnson and Oliver, “and he was going to do whatever he wanted to do and with whom he wanted to do it with.”

“One of the things that’s made what we do a little bit unique is trying to make sure there’s a human element and not just a recitation of fact in the stories we do,” says Johnson. “The things that made wrestling attractive to me in the first place is the characters and the stories, not the won/ loss records.”

Illustrative of how little wrestling has changed since its early days, The Storyteller opens with the story of Parson Davies, a Chicago-based sports promoter in the second half of the 19th century who branded his matches as “athletic entertainments” to skirt complaints from local decency groups. Davies was a hundred years ahead of Vince McMahon, the CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), who coined the term “sports entertainment” in the 1980s to attract advertisers and skirt oversight from state regulators.

Jewells Malone. Photo: Beanz Wrestling (couresty of ECW Press)

What has changed perhaps most dramatically in wrestling is the access fans now have to performers. Wrestling promoters in the 1970s were well-known for enforcing strict rules that ensured that opposing wrestlers would not be seen traveling together or sharing locker rooms. Sustaining wrestling’s fantasy world was critical to its success for most of its existence. Wrestlers now grant fans access to all areas of their personal lives, and the most famous have carefully crafted social media presences.

Johnson and Oliver have tracked the generational change firsthand. “I think wrestlers now have been taught to be a lot more protective and it’s not any different from the NBA, or whatever it is,” says Oliver. “They have handlers. They have social media people looking out for them. All that kind of stuff. Who’s managing their social media accounts… you don’t even know anymore.”

Storytellers is being published at a compelling point in wrestling history. The amount of success achieved by Vince McMahon is without parallel. While wrestling’s most famous performers have generally been well-compensated, for the vast majority, their careers have been nickel-and-dime affairs. That a third-generation promoter like McMahon could now be worth billions of dollars is beyond what anyone could have ever considered possible.

McMahon took the WWE public in 1999, and the company now produces films and has cultivated multiple mainstream stars, like Dwayne Johnson, Dave Bautista, and John Cena. “WWE has all these contracts, like the new one coming up with Fox to air SmackDown,” says Oliver. “That’s a really big deal that you couldn’t have imagined happening back in 1985 when they were trying to expand.”

The success brings pressure to conform with mainstream tastes, however, a challenge that professional wrestling, long considered the embarrassing sideshow of sports, has traditionally struggled with. “One of the theses of The Storytellers is that since the very beginning, pro wrestling has walked this tightrope between being true to its carnival origins and trying to garner mainstream acceptability,” says Johnson.

“It’s almost a zero sum game. You garner too much mainstream respectability, you get away from the carnival roots and unscripted wackiness that gives the sport so much of its flavor. You go too much toward the hokum, and you run the risk of losing whatever mainstream respectability you had in the first place. That’s the tension that wrestling’s had since the beginning.”

To their enduring credit, Johnson and Oliver have eagerly documented the hokum as lovingly as they have wrestling’s less outrageous elements. Through their work, they’ve helped create a record of the lives of the strangely talented, impossibly dedicated performers of professional wrestling.

“The late wrestler Paul Jones told me that he remembered Bob Hope saying at one point that wrestlers were the greatest storytellers in the world,” says Johnson. “In the space of just a few minutes they could make you laugh, they could make you cry, they could make you cheer, they could make you shake your fist in anger. I looked for a long time for that quote. I don’t think he made it up but I couldn’t find anywhere where Bob Hope was on record saying that. That’s kind of where the idea of storytelling comes from. The alternative phrase, and you hear this all the time with wrestlers, is ‘painting the canvas.'”

In their time working together, Johnson and Oliver have come close to hearing thousands of stories. Taken as a whole, they form an essential part of pop culture history. “Who else alive has ever interviewed Tony Olivas?” says Oliver. (Olivas began his career in the 1950s as the Elephant Boy and later became a Catholic priest.) “Who else is documenting this stuff? There’s so much chasing of the top guys that the lesser guys get forgotten. They have better insight, in many cases, as to how pro wrestling works and to why they did it.”