Last year I had the pleasure of reading Barney Rosset‘s fascinating memoir, Rosset: My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship (OR Books, 2017). I knew him, as most readers do, as the founder of Grove Press and Evergreen Review, the man who published D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer amid landmark court cases, and even as a man who distributed landmark films like Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) and I Am Curious (Blue) (1968). There was a 2008 documentary about him, Obscene, by me unseen (no pun intended).

The book taught me that Rosset initially wanted to be a filmmaker like his school chum Haskell Wexler, and that his first serious project was a documentary feature called Strange Victory. Described as a film about American racism, it was completed in 1947 and played in one New York theatre rented by Rosset to underwhelming business and contradictory or condescending reviews. Thus, a failure, and one that encouraged Rosset to go into a safer field: publishing!

I remember thinking it would be nice to have a look at this obscure failure in American cinema, and also how unlikely that prospect seemed. Ask and ye shall receive: one year later, here’s that film in razor-sharp 2K restoration on DVD or Blu-ray from Milestone Films.

The film is structured as a persuasive essay-lecture that consists almost entirely of newsreel footage mixed with several minutes of new film. In fitting together previously existing documentary footage for the purpose of telling a new narrative that arises from their juxtaposition, the filmmakers were emulating the pioneering work of Russian “found footage” documentarian Esfir (or Esther) Shub. They were also remaining true to their own experience, for producer Rosset had been trained as a photographer in the Army Signal Corps during WWII, while director Leo Hurwitz cut his teeth with the Workers Film and Photo League.

This League, founded in 1930 during the heart of the Great Depression, wished to document workers’ and underclass struggles in political demonstrations and the resistance they faced from authorities. Examples, as bonus films on this disc, include newsreels on “hunger marches” and “bonus marches” made on Washington DC by unemployed residents of “Hoovervilles”. These silent newsreels have new piano scores by Ben Model.

A special film is the last one, Pie in the Sky, not a documentary but a sour comedy with a message against the pieties of religious relief. Young Elia Kazan co-stars with Ellman Koolish as the hobos who cavort in a dump in a manner resembling the provocations of Luis Buñuel’s The Golden Age (1930) without quite going that far. It’s eye-opening that anyone in America made such a movie so far from Hollywood. Also involved were Irving Lerner and Ralph Steiner, who moved on to significant careers.

So did Hurwitz, who founded a subdivision called Nykino and then his own Frontier Films. He worked on Pare Lorentz’s landmark The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), with music by Virgil Thompson (an important detail to bear in mind) and co-directed the indie pro-union docudrama Native Land (1942), narrated by Paul Robeson. He made WWII propaganda for the Office of War Information and other government agencies and then moved into forming early news programming for the fledgling CBS TV network before the coaxial cable facilitated national TV networks.

In other words, Rosset picked the right man to write and direct this project. Rosset’s main job, as he explains in a 2004 bonus interview, was securing all the newsreel footage from multiple sources, mainly American and European government archives, including Czechoslovakia, the only Iron Curtain country that agreed to distribute the film. Thus, we get a kaleidoscope of amazing footage of suffering and horror of the recent war. As Rosset’s interviewer observes, it’s not footage duplicated elsewhere.

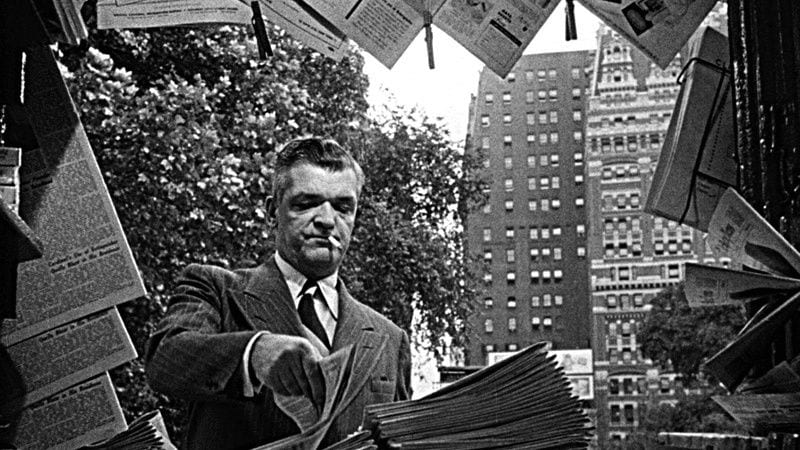

The film opens with the camera looking outward from inside a news kiosk, as various people approach to look at the headlines while hurrying past. Narrator Alfred Drake (yes, the Broadway singer best known for Oklahoma), speaking narration written by future playwright Saul Levitt after watching the rough cut, asks why, if we won the war, our worried faces look as if we’ve lost. “Remember how it was?” he asks, as the film “remembers” the war footage that comprises the first act of struggle and victory.

That’s the thesis: we won the war against fascism. Then comes the antithesis: things are back to pre-war “normal” in an America where the old prejudices remain. The film focuses especially on Jim Crow and racial issues, with some mention of anti-Semitism and anti-Catholic sentiment. We see lots of signs for country clubs and housing divisions that say “restricted” and “exclusive”, words that sound benign until you understand the meaning. We see shocking images of lynching that compare with charred corpses of the Holocaust. This idea ties in with the first part’s observation that Hitler “disappeared”, that his body wasn’t found. The implication is that his spirit, fueled by “whispers”, has survived and will revive. The idea is underlined by reverse footage to show time running backwards.

The documentary footage gives way to a little drama about an African-American airman played by Virgil Richardson — one of the famous Tuskegee Airmen — who can’t get a job in civil aviation after the war, although there are plenty of openings for janitors and waiters. The film closes on sad statistics about the percentages of “Negroes” in middle-class jobs.

A special element of the film is the dynamic symphonic score by David Diamond in full bustling mid-century Americana mode. As Rosset recalls in the interview, he met with Leonard Bernstein for the project and Lenny brought along Diamond, handing off the job to him. An uncredited Virgil Thompson arranged and conducted the score. By the way, another voice heard on the soundtrack is Gary Merrill, future husband of Bette Davis.

What’s sobering isn’t how the film reflects its own time, but how much it compares with today. In 1964, Hurwitz added an epilogue with footage and speeches of the Civil Rights era, and this is included as another bonus. Despite the Voting Rights Act, the legal dissolution of Jim Crow, and the growth of a black middle class, the viewer won’t feel that today’s numbers reflect such a dramatic improvement. Nor can we tell ourselves that the spirit of racial prejudice and scapegoating, which the film explicitly identifies as a fascist tactic, has vanished from politics.

In a bonus 1992 interview, Hurwitz recalls that the critical reception of this movie scotched his chances of a job offer at the DuMont Network. He says that the conservative New York Daily News reviewer opined that behind the film was “the voice of Stalin”, since clearly only a commie would point out problems of racial prejudice as no upstanding Americans ever noticed such things. The interviewer says Hurwitz was blacklisted from TV for several years. In practice, this meant he worked without credit on certain projects, especially Omnibus. After the blacklisting was lifted, he won an Emmy and Peabody for his program on Adolf Eichmann’s trial.

Strange Victory isn’t only an important and oddly overlooked piece of history in the American documentary movement, or an important work in the lives of several important Americans known for more famous accomplishments. By itself, it’s a strong piece of work that documents its convulsive recent past, ties it into a contemporary scene that we often forget was almost as convulsive — for it wasn’t commonly presented in escapist media — and finally, unwittingly, links itself to still roiling convulsions of the film’s distant future.

We would love to call this a “dated” film of interest only for quaint historical value, but we can’t get away with that luxury. It’s a film that still asks pertinent questions as it holds up a mirror to modern America. We don’t know if this is part of a broader Barney Rosset revival (perhaps more of the films he distributed can be unearthed?), but Milestone deserves thanks for ferreting out this golden nugget from the detritus of film history, just as its conscientious makers deserve thanks for swimming against complacent tides, either of postwar ennui or desperate cheerleading.