Architecture is an apt subject for comics, the way a page’s layout can resemble a grid of windows or a blueprint of flowing rooms. That visual parallel, however, is not what fuels Viken Berberian and Yann Kebbi‘s architecture-driven graphic novel The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade, a dystopic rendering of post-Soviet Armenia through the clouded eyes of a well-meaning but destructively naïve city planner.

Instead of traditional layouts of rectangular panels and uniform gutters, Kebbi renders a violently chaotic world consisting entirely of colored pencil lines charged with gestural energy in overlapping and often literally scribbled shapes. Where traditional commercial comics feature a penciled draft that’s later inked for clarify and then colored in discrete forms, Kebbi combines the three production stages into a single visual structure that’s intentionally at war with itself. His final pages often include and even highlight what appear to be the light lines of his initial sketches, with some sections left untouched.

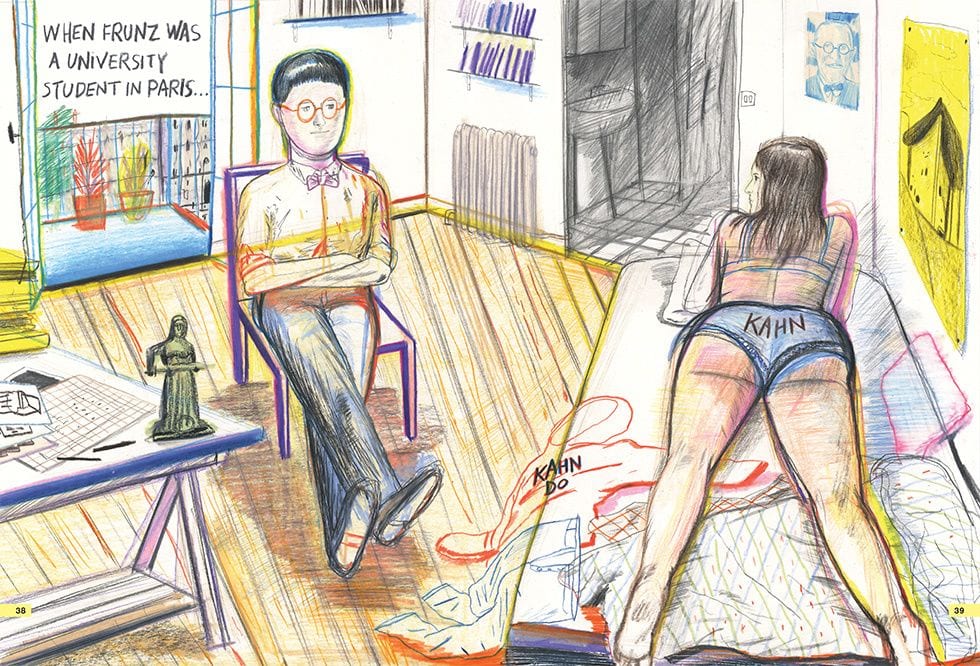

Other areas of the same pages are drawn over multiple times, often in multiple shades of pencil, producing a thickness at odds with the sparseness of adjacent and sometimes even intersecting images. Because no shape has authority over any other, figures seem transparent, the lines of streets and buildings visible through the unfilled sections of their bodies—even when other sections of the same body are carefully crosshatched.

Kebbi’s drawing style is at war with itself, too. While obviously skilled in naturalistic norms of perspective and figure drawing, he’s just as prone to toss those norms aside to create the impression of a child crayoning. Even individual figures are stylistically contradictory, with a face and head precisely sketched but the rest of a body truncated into cartoonish proportions. The cartoon norm of blurgits—the drawing of multiple limbs to suggest one limb in motion—is oddly static in effect here, as if Kebbi had sketched several limb positions and then couldn’t decide which to finalize. The combined product is a world teetering on carefully crafted incoherence—which is well suited to Viken Berberian’s script.

The first 100 pages feature the young architect Professor Frunz leading his graduate students through the streets of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, a country land-locked between Turkey, Iran, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, but as part of the former Soviet Union, still highly influenced by Russia. As Frunz discusses the city’s architecture, both current and the vast plans he and his architect father are in the process of implementing, wrecking balls swing around them. The balls are literal—prompting one of the students to shout “Duck!” to her professor, while a man reading a newspaper on a stool is struck and dies in a puddle of his own blood—but also cartoonishly and satirically surreal.

As the professor continues his tour, he drags homeless people clinging to his ankles.This is not the actual city of Yerevan, but rather its reflection in Berberian and Kebbi’s political funhouse mirror. Frunz, the novel’s main character, is not its hero but the main object of its derision. The former homes of the now homeless were bulldozed to make way for the father and son’s grand revisioning of the historic city—which means destroying the Soviet-era farmer’s market to build a solar-paneled supermarket amid all of the new high-rises, even though, as one student points out, Yerevan is a seismic zone. If all goes on schedule (which it won’t), the homeless will be homeless for only five years. Meanwhile, they’ve each been compensated with a three-legged stool.

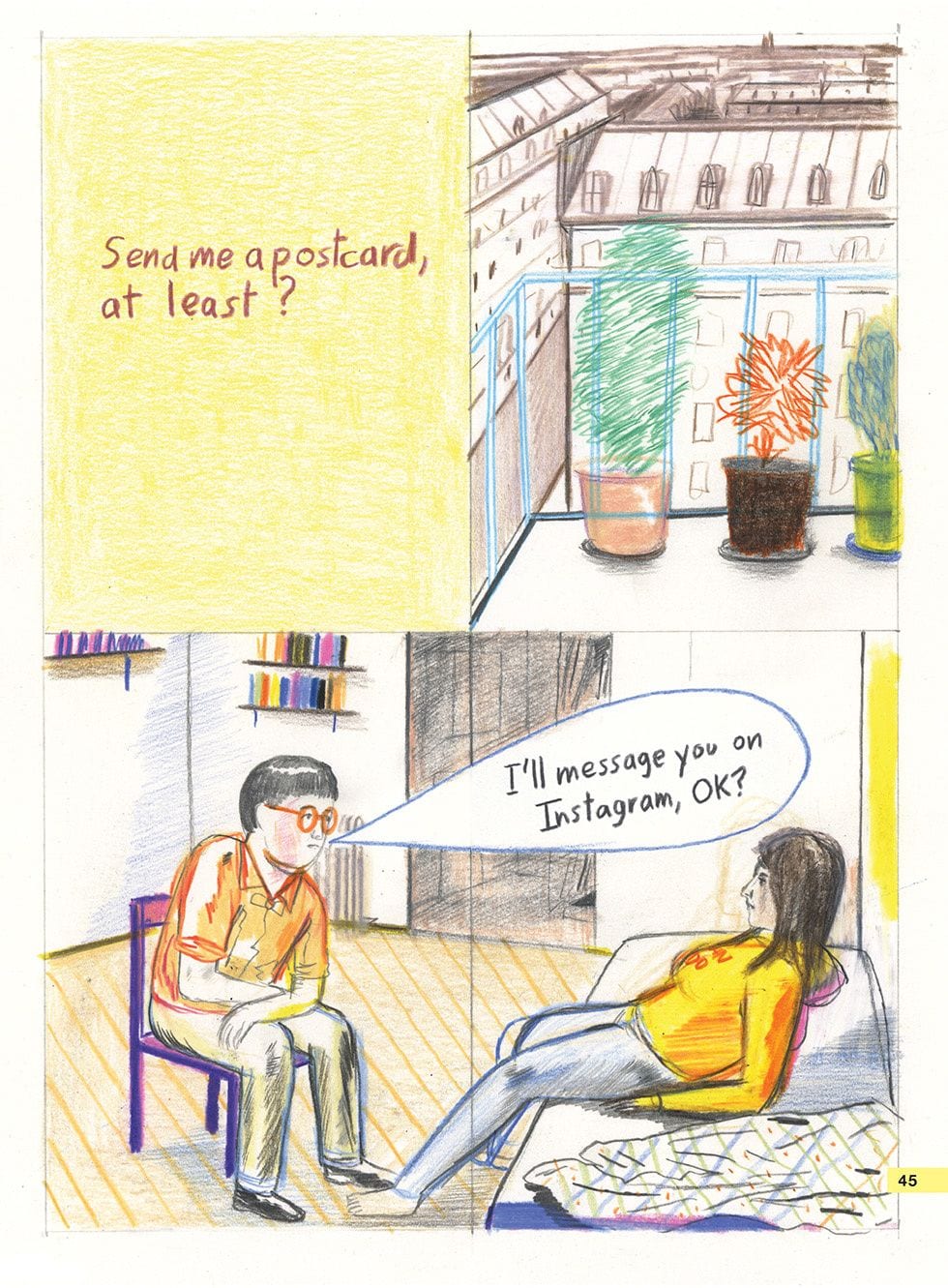

Berberian provides his young professor a complex backstory, told in vacillating sections during his strolling lecture. The time divisions—like most other divisions in the graphic novel—are often hazy, but Kebbi wisely renders the past mostly in gridded layouts, as we follow Frunz through his Parisian childhood (his first word is “sea mint”, which his architecture-obsessed mother mistakes for “cement”, tragically shaping his later obsession), his Parisian university years (he and his girlfriend emotionlessly part ways after he drops out to work with his father), and his visit to Moscow (where Pussy Riot makes a memorable ten-page cameo as they storm a historic church, with one of the women screaming, “Fuck this. I should have studied architecture instead,” as she’s handcuffed and kicked by police).

One of the novel’s running jokes is the absurdly large-breasted graduate student wearing a t-shirt with the phrase “Less Is More” (which, I was surprised to learn from the endnotes, originated as an architectural concept in the late ’40s). By the end of the lecture tour, she is inspired to cross out “Less”, revising the phrase to reflect the Frunz parody-philosophy of “More is More”. The visual joke gets old though, since the woman and, more importantly, her cartoonish breasts appear more than 30 times in the first 100 pages. Given the radical instability of Kebbi’s cartoon reality, did her breasts really have to be one of the few consistencies?

Though she and the other graduate students vanish after page 105, Berberian and Kebbi still have another 200 pages in store for Frunz. After also abandoning their alternating flashback structure, they introduce a homeless antagonist, the same one previously glimpsed grasping at Frunz’s legs, only now he has his own lines of dialog (rendered as free-floating words on the open page, the balloonless style Kebbi uses for all of his dialog). Plenty more chaos follows, with rebels and military clashes and many many more wrecking balls.

I doubt it’s giving much away to reveal that young Frunz eventually learns the error of his ways—because, even if he didn’t, that parodic lesson is the DNA of the novel. It also means that the transformation isn’t especially relevant or convincing since his character is so intentionally two-dimensional, a cardboard placard for his authors’ political commentary. Still, the hints of a deeper character do filter through Kebbi’s scribbles and Berberbian’s absurdist dialog—enough that I was glad when Frunz escapes the chaos of Yerevan he helped to create and returns to Paris. Sadly, this is no longer the Paris of our own world—not because of Kebbi’s chaotic artistic style, but because here Notre Dame remains intact and unburnt, a coincidental but haunting fact for a graphic novel about the destruction of historic architecture.