Re-Run Heaven

A prepubescent memory: Right around my bedtime, the children’s cable network Nickelodeon became Nick-at-Nite, a block of sitcom reruns I could only stay up to watch during summer vacation. This meant many a heavy-lidded July marathon of Get Smart and Welcome Back, Kotter activity that now strikes me as a kind of antiquing. This was the same archivist’s impulse that would take me on countless record-store digs in my adult life, digging through used LPs and buying vinyl that was manufactured before I was born.

To distinguish itself from the rerun dumping ground on network TV, Nick-at-Nite ran bumpers—little non-ads that tied their programming block together with cheeky bits of retro kitsch. One such bumper featured a Barbara Eden look-a-like dancing seductively to a song based on I Dream of Jeannie. For the refrain, a girlish voice sang the melody from Jeannie‘s theme song. I was enchanted. This is my earliest memory of thinking that something is sexy. And it wasn’t just faux-Eden. It was the bass, those drums, those silky synths, those sly staccato horns. This music was sexy. And I barely knew what sexy meant.

It wasn’t until a few years later that I realized this song was a parody of a “real” song, which is now one of my favorite things in pop culture. It’s catchy, it’s coy, it’s fun to dance to, and it’s sexy as fuck.

Sexy?

What makes a piece of music “sexy”? What makes anything sexy, for that matter? The word is almost never used to describe actual coitus—”Man, that was some sexy sex!”—but it might be applied to, say, the seam along the back of a woman’s stocking. “Sexy” is indirect. It depends on some web of memories and associations.

If sex was the first pleasurable activity discovered by human beings, music was probably the second. (Perhaps the joy of making rhythmic sounds was actually discovered during sex. Makes sense, right?) The intimate relationship between sex and music is no secret. Dancing. Courtship. Wedding processionals. Mating calls. Luther Vandross. Do I need to remind you that “jazz” and “rock ‘n’ roll” are both (allegedly) terms with etymological roots in sexual slang? Do I need to point out the phallic or conic nature of many instruments devised by humans to make pleasing sounds? Why did you start a rock band as a teenager? It sure wasn’t to discourage the idea that you were a viable sexual option.

Genuinely sexy music is a rare commodity, however, and for that reason, it is worth considering where it comes from and how it gets here, just as it is worth considering why the music that tries the hardest to be sexy fails so miserably.

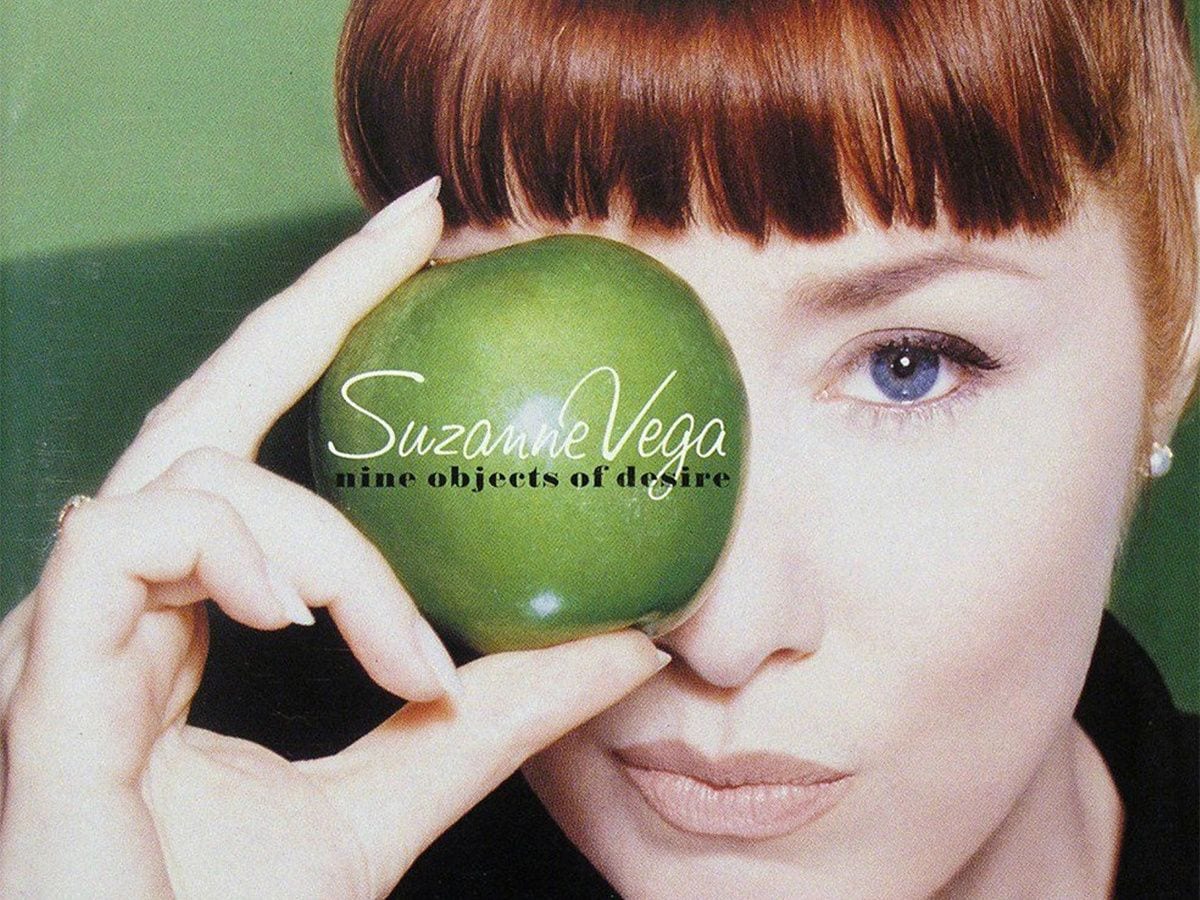

Seduction Through a Pane of Glass: Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner”

In Suzanne Vega’s ” Tom’s Essay” (New York Times, 23 September 2008), she explains how “Tom’s Diner” came to be: It was 1982. She’d get her coffee at Tom’s Restaurant, which you’ve seen in those exterior shots during episodes of Seinfeld. A photographer friend had said he “felt as though he saw the world through a pane of glass.” Vega wanted to write a song from that point of view.

In the (much remixed and sampled) song, a narrator observes others in a series of intimate moments: Two people embrace. A woman’s hair has gotten wet from the rain. The narrator reads an obituary for an actor who died “while he was drinking”. (It was a real obituary. The actor was William Holden, and Vega, as the lyrics suggest, hadn’t heard of him.) The narrator observes passively, finally remembering a midnight picnic before “it’s time to catch the train”. The closing bars feature a wordless adlib: “Dat da da da…”

The song appeared in a cappella form at the top of Vega’s 1987 Solitude Standing album, where it was overshadowed by the following track, “Luka”, which became her biggest hit—number three on the top 100 at one point. “Luka” is a song about an abused person whose downstairs neighbor has overheard her domestic situation through the floor.

Vega had already released a follow-up album by the time someone told her that a British duo had created an unauthorized, white-label remix of “Tom’s Diner”. Rather than sue their asses off, Vega arranged to release the remix officially—permissions, fees, and all that.

I don’t know where I first heard the DNA remix, but I know I was only momentarily confused by the non-sitcom lyrics, quickly understanding that faux-Eden had been gyrating to a parody. This was, I thought, the original.

Incidentally, my first exposure to many pop-culture artifacts first happened indirectly like this. Looney Tunes (and its 1990s offshoot Tiny Toon Adventures) exposed me to all kinds of things I initially assumed were outlandish creations of an animator’s mind, only to later discover they had serious adult antecedents—Humphrey Bogart, stuff like that. I remember loving the Muppet Babies episode that spoofed Star Wars years before I saw the actual trilogy. And so it was, briefly, with the DNA remix of “Tom’s Diner”, which I only knew as a late-night parody of other people’s nostalgia before I discovered the “original”.

The DNA remix—the “original”—repurposes Vega’s “Dat da da da” adlib as a chorus and lays her voice over the drums from “Back to Life”, a track from Soul II Soul’s dated, but pleasingly smooth-as-silk album Club Classics, Volume One. Those drums are a looped break from Graham Central Station’s “The Jam”, from their 1975 album Ain’t No ‘Bout-A-Doubt It. What you’re hearing is a few seconds of Manuel “The Deacon” Kellough’s drumming.

That break was also sampled in “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” by the Geto Boys and “’93 ‘Til Infinity” by Souls of Mischief. The latter’s instrumental has become the hip-hop equivalent of a jazz standard; mixtape rappers can’t resist taking a crack at it. It’s interesting to wonder if the Deacon would have played any differently if he’d known how his playing would be used.

Likewise, it’s interesting to wonder how Vega would have recorded her vocals if DNA’s beat came first, if she was singing to the pulse of that kickdrum in her headphones. Her lyrics describe a woman straightening a stocking just outside the diner. (“Does she see me? No, she only sees her own reflection.”) That woman, like the Suzanne Vega we hear on this record, is perfectly unaware that her solitary moment will become a part of someone else’s song. I wonder if the perfect, unassuming intimacy of Vega’s vocals would have been impossible if she had known while singing that this moment would be repurposed by strangers as an apparition of allure.

iVega

An advantage of the MP3 revolution was the way it enabled the purchase of individual songs, even if a physical 45 or CD single (remember those?) could not be found. So instead of paying $11.99 to get all the other shitty songs by Primitive Radio Gods when all you really wanted was “Standing Outside a Broken Telephone Booth with Money in My Hand”, you could pay $0.99 for just that song. Cool. The first MP3 I ever bought was “Tom’s Diner”.

When the MP3 format was first developed, the a cappella “Tom’s Diner” was used to perfect it. What better reference point than the naked human voice? Any distortions would be immediately apparent. An MP3 is a distortion, however. While the format was designed to replicate sound with what appears to the naked ear as total accuracy, information is actually lost in the transfer of analog-recorded sound into MP3.

In 2014, sound artist Ryan Maguire, as part of a project called “Ghost in the MP3”, created a piece of music that uses the audio that is lost when the a cappella “Tom’s Diner” is compressed to an MP3. It’s a beautiful piece with an apt title. Elusive bits of voice kind of swirl around you, trying to pull themselves into something whole. You can recognize the melody and the sound of Vega’s voice.

“Tom’s Diner” is in there, it just sounds like there’s a pane of glass between you and it. The effect is somewhere between hearing your upstairs neighbor through the floor and the distant morning-after memory of a song you heard during a fantastic night. After The DNA remix and Vega’s a cappella, Maguire’s permutation is my favorite. Anyone looking to hear others should be warned.

In 2015, Giorgio Moroder put out a cover of “Tom’s Diner” with Britney Spears on vocals. It’s a graceless dud that replaces Vega’s wistfulness with the brand of trying-too-hard sexiness that has been Spears’ trade for a couple of decades now—the kind of thing an inexperienced person might find sexy before realizing it’s a grotesque parody of actual sexiness. At one point, an auto-tuned male voice—Moroder’s, I guess—can be heard singing a collection of blunt let’s-party slogans like “Everybody’s welcome” and “come on in” and “sit yourself down” and “love is the drug”. Remember, this is a song set in a coffee shop. And in these hands, Tom’s Diner becomes a party-bus orgy.

I expect this kind of bullshit from Spears, but I’m disappointed in Moroder. This is Giorgio Moroder—the man who co-wrote Donna Summer’s slinky epic “Love to Love You, Baby”. While that side-long come-on may have laid it on a little thick, it still gets a place in the exclusive “genuinely sexy” category, thanks to the groove laid down by the bass and electric piano. (The sexiness in “Love to Love You, Baby” actually happens in spite of Summers’ orgasmy moans and coos.) Moroder’s best work with Donna Summer was musical seduction. The best Moroder and Spears can come up with is the musical equivalent of shouting, “Hey! Let’s fuck!”

If that isn’t bad enough, listen to “Centuries” by Fall Out Boy, which samples Vega’s “Dat da da da” adlib in the service of one of those stadium-ready rock tunes designed to sound really, really big and earnest without containing anything potentially alienating like specificity or creativity. At one point, trap-rap-samplepack drums accompany a chorus of voices mimicking Vega’s hook before a histrionic lead singer belts out the line “You will remember me for centuries”. (It’s, like, real passionate and shit.) At one point, you’ll hear what I can only assume is a field recording of the stiff clapping from one of those big Caucasian megachurches. We’re a long way from reading the paper at Tom’s.

Vega’s song doesn’t ask you to feel anything, while Fall Out Boy practically begs you with a come-on made from “anthemic” signifiers and evangelical gestures. While Vega sneaks a glance over her cup of coffee, Fall Out Boy are throwing their arms around your neck while they double-fist PBRs. (Play it cool, boys, nothing intimate ever happened in a stadium.)

If you want to hear several permutations of “Tom’s Diner” all at once, check out Tom’s Album. Vega compiled it herself, and it collects covers and parodies. It’s nice to see someone so comfortable with her work being borrowed. In that New York Times piece, Vega says she’s only ever turned down one request to use “Tom’s Diner”—when someone wanted to use it in pornography.

I find that fact revealing. The allure of “Tom’s Diner” is totally contrary to the premise of pornography. Vega’s song marinates in the quiet jouissance of watching and remembering. The periphery is the center. She is “trying not to notice” the woman outside “hitching up her skirt”. She is “thinking of your voice”. Vega’s performance enacts desire, and that desire is indirect, intimate, specific, and fully hers, even when it is incited by the intimate moments of others. (“I look the other way as they are kissing their hellos”.)

Vega is not the object of desire, like Spears, or the thing to be remembered, like Fall Out Boy. Her desires—made from her memories and her view through the glass—are what matter. Spears and Fall Out Boy, on the other hand, try to universalize. That may be how pornography works, but it is not how desire works, and this difference is the key to the coy allure of “Tom’s Diner”.

Afterglow

I found faux-Eden again in the bottomless rerun dumping ground of Youtube. Her dancing isn’t nearly as suggestive as I remembered, and I’d forgotten that scenes from

I Dream of Jeannie are projected on her fit midriff. It’s pretty silly. The music lacks a little of DNA’s impeccable production, but it’s basically a faithful copy. I like that the artifact that initiated my concept of “sexy” is so derivative and sweet. It’s a few steps removed. Indirect. Coy.

Now, whenever I happen upon “Tom’s Diner” during a record-store dig, I buy it. Usually, it’s the 12” single containing the DNA remix as well as Vega’s a capella. I give away my extra copies, the way you can’t give MP3s as gifts. I’m not sure why I do this. It seems odd to evangelize something tied intimately to a distinct memory of sexual awakening. These things typically remain behind veils.

One more thing: The lines about the midnight picnic are excluded from DNA’s remix. For anyone familiar with the a capella original, though, the image remains. Perhaps it remains under erasure. Perhaps it lingers for these listeners as a memory the same way it lingers for the woman reading the paper in Tom’s Diner. Your call. In any case, the veil between the listener and the lyric’s most vivid image of intimacy is one last layer of seduction. She is thinking of your voice.

- Ordinary Magic: Suzanne Vega's 'Days of Open Hand' - PopMatters

- Suzanne Vega: Close Up, Volume One, Love Songs - PopMatters

- Suzanne Vega: Beauty & Crime - PopMatters

- Suzanne Vega: Retrospective: The Best of Suzanne Vega ...

- Suzanne Vega: Songs in Red and Gray - PopMatters

- Ordinary Magic: Suzanne Vega's 'Days of Open Hand' - PopMatters