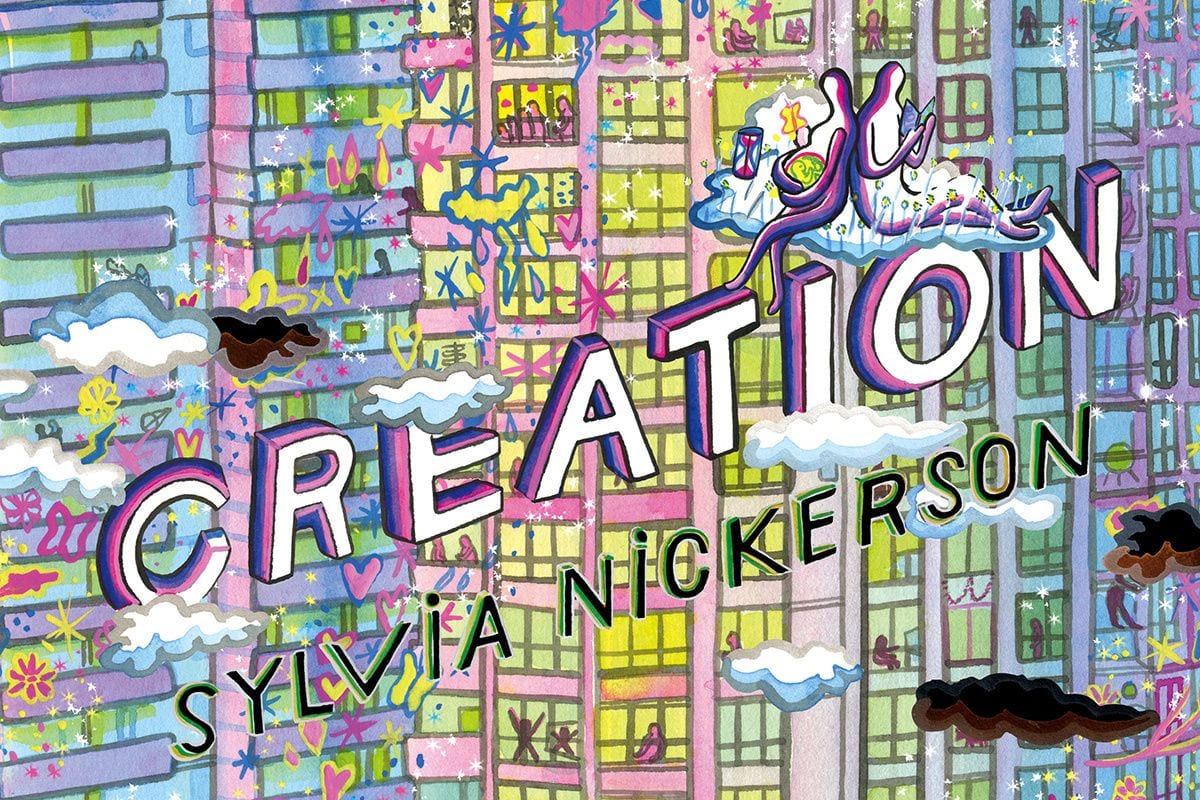

Sylvia Nickerson‘s title, Creation, has at least three meanings: art, babies, and all of existence. Nickerson has lots of first-hand creative experience with the first two categories. She is a widely published comics artist and, according to Creation, the single mother of a child named Toby. Though the third category should be God’s handiwork, it’s not clear from the graphic memoir whether such an entity exist. Either way, most of the problems Nickerson sees plaguing creation appear to be human-made.

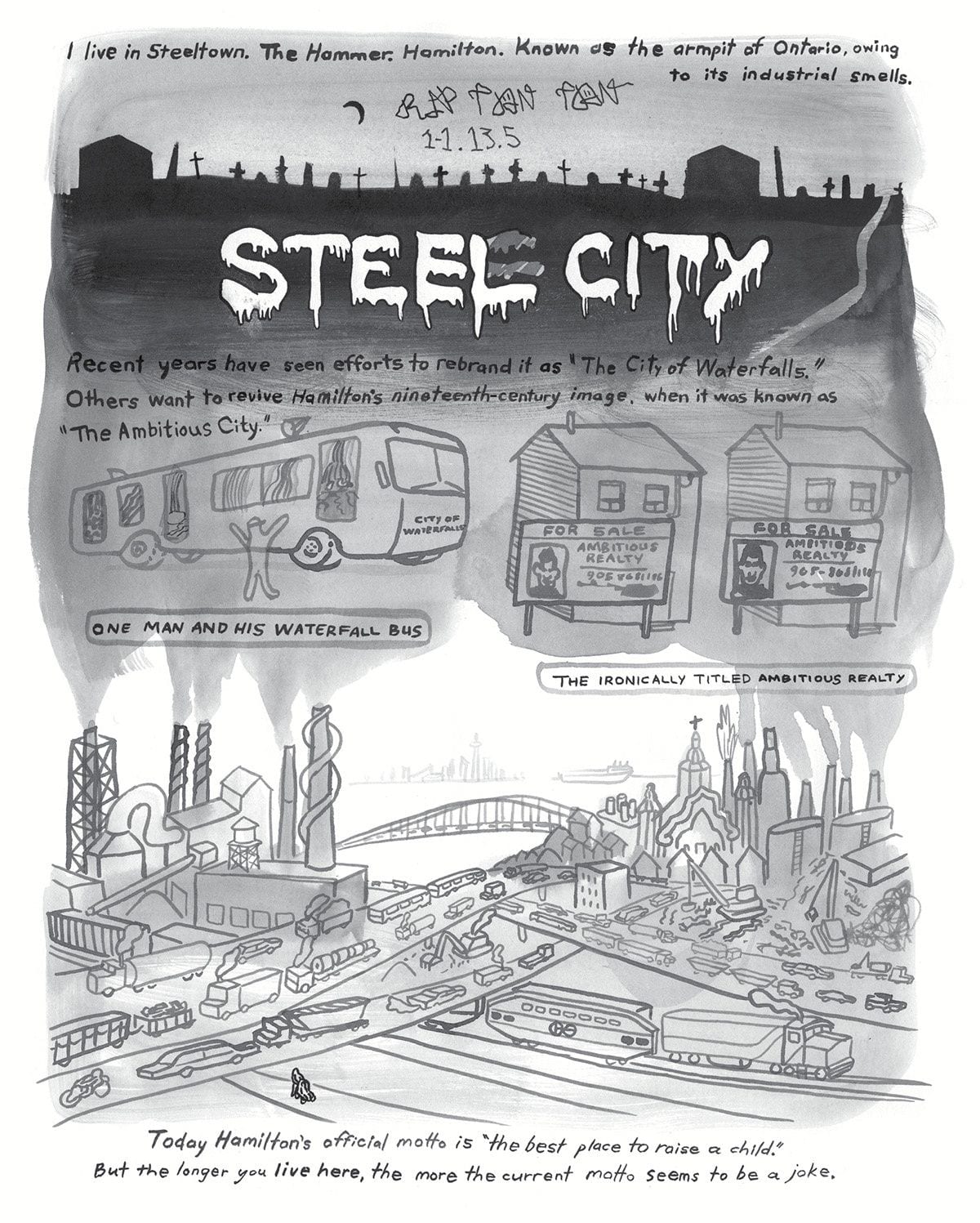

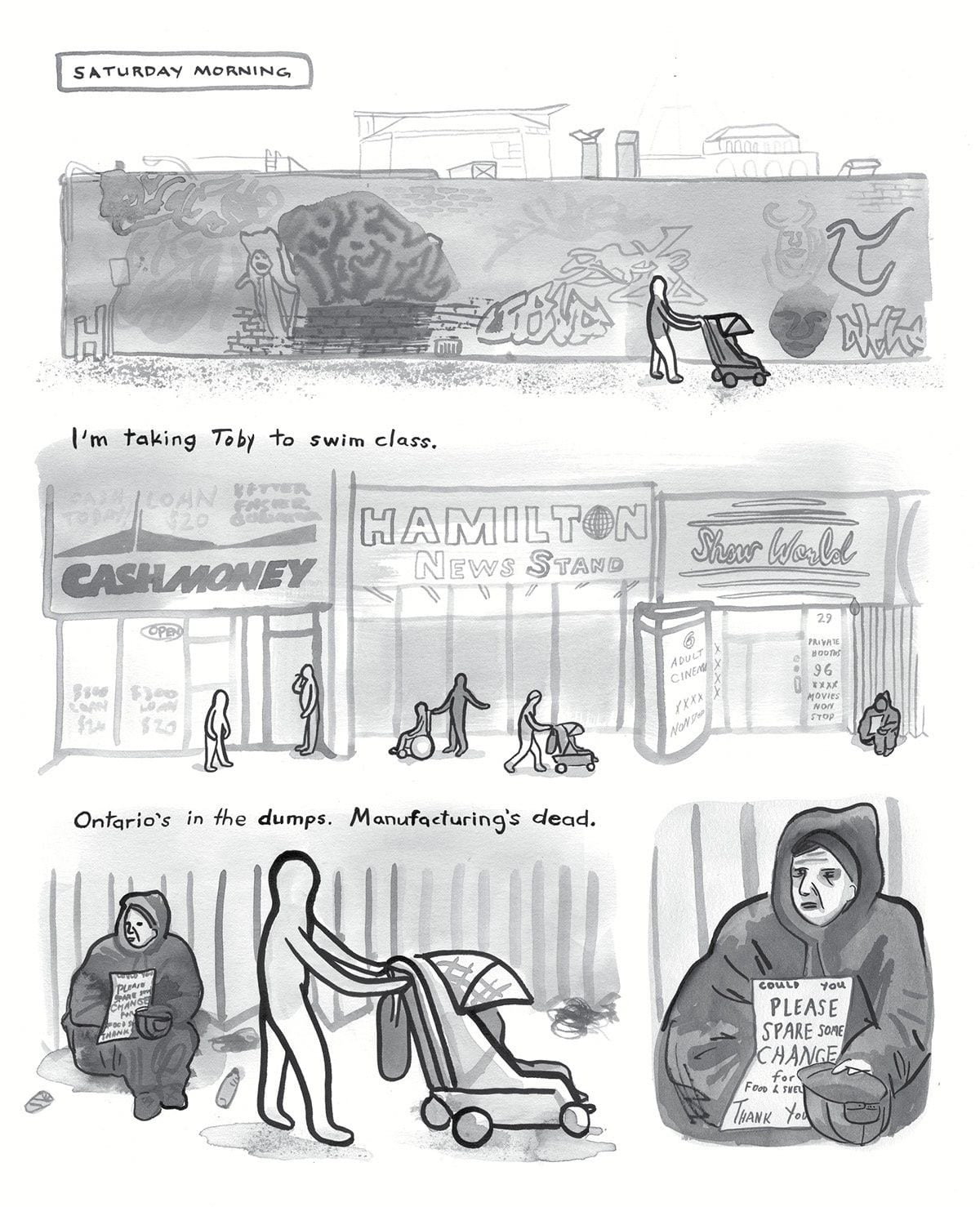

Though Creation opens with daily domestic scenes of mother and newborn, it’s not that kind of memoir. Nickerson’s view is more panoramic, taking in all of her home city of Hamilton, Ontario. That wider thematic focus is apparent even when her immediate attention is on herself. She draws herself and Toby and most other characters in an aggressively indistinct style. Technically the figures are cartoons, at least in the highly simplified sense, but though they are exaggerated too, it’s through atypical compression.

Rather than the giant heads of, say, Charles Shultz’s Peanuts characters, Nickerson’s people are boiled down to a few curving shapes and a wash of interior gray that’s barely discernible from the grays outside their nominal bodies. They have no fingers. They have no necks. They have no faces. But they’re not rough sketches either. Their bodies are lit three-dimensionally, with differing areas of shadow. It’s as if Nickerson is drawing naturalistic renderings of actual blob-like people.

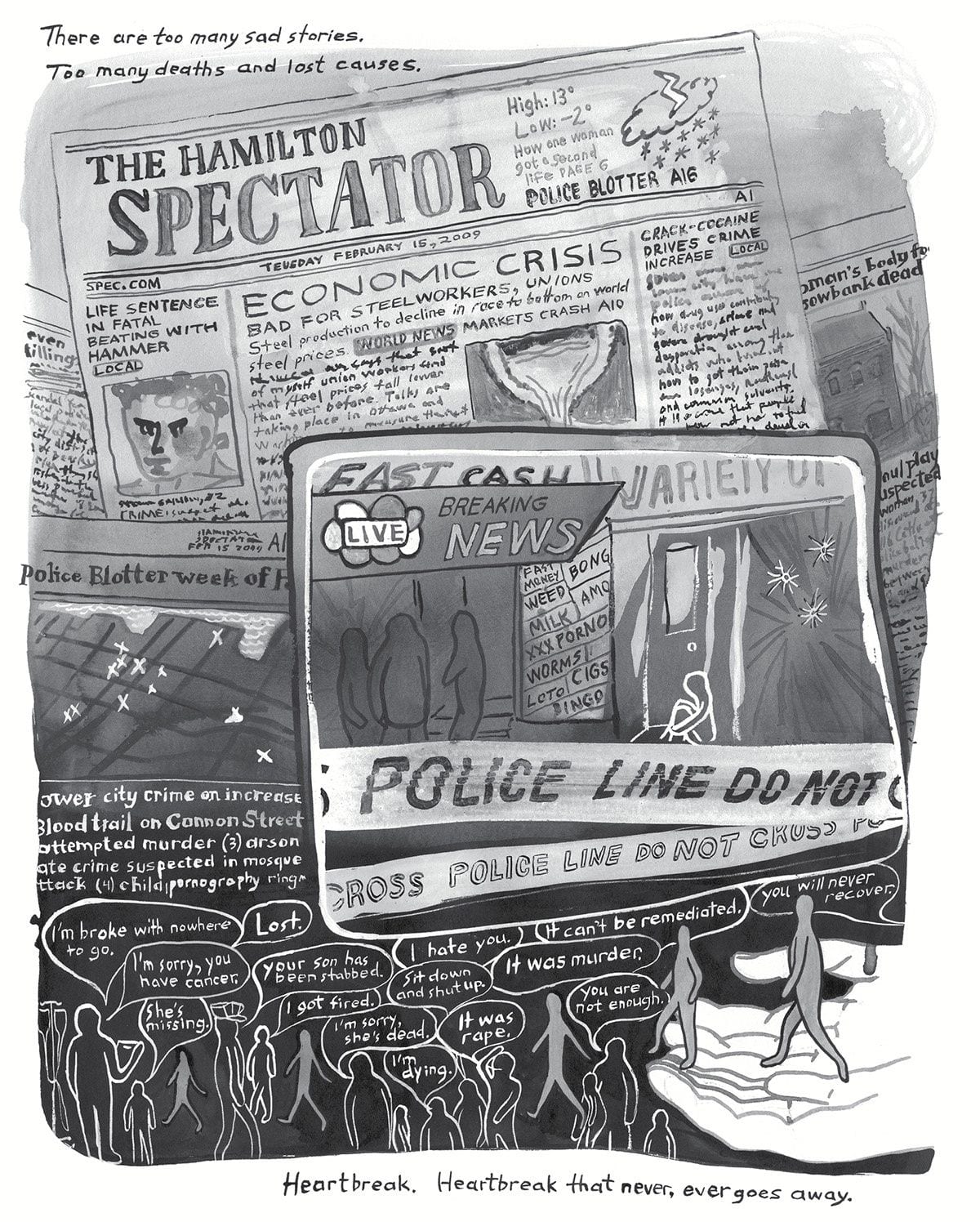

But not always. She breaks form several times in order to provide a detailed portrait of an individual character. When she and her son look inside a dumpster, Nickerson draws the sleeping homeless person inside not only in a larger panel, but in reversed white on gray lines that detail his clothing. When a homeless woman asks her for money, Nickerson fills a panel with her carefully lined face. The woman’s name is Nancy, and she becomes the center of the memoir.

(Drawn & Quarterly)

(Drawn & Quarterly)

(Drawn & Quarterly)

The differences between the two sets of characters, the realistic homeless and the blob-like privileged, establishes the book’s central dichotomy and critique. It’s not just that Nickerson portrays the two groups as different species. The homeless are human, and the privileged are subhuman.

Nickerson makes no exception for herself. Much of her memoir is a self-indictment. When it opens, she is a successful artist in a gallery on James Street, the front line of Hamilton’s gentrification battle. She hardly thinks about the people in the neighboring buildings whose rents are rising beyond their income as the real estate under their feet grows in value. Nickerson draws herself and Toby’s ever-present stroller parked outside a quaint, corner café, while a panhandler stands further down the block, across the street from an abandoned, window-shattered factory.

Though distant, the panhandler’s face is still a face, while Nickerson’s is featureless. Her visual approach reverses and so reveals her own psychological state at the time. Though content with her own dream-come-true art studio, she writes: “How could I ignore that this same place was where so many dreams had come to die?” The question is answered by her visual style. She refused to see homeless people as people, and now when drawn retrospectively, she is the one who appears subhuman because her willful ignorance lessened her.

Though her images remains blob-like, Nickerson still explores aspects of her very real personal life. Single parenthood is a struggle. The mystery of her child’s father is evoked but never resolved. She would rather list historical and statistical facts about the city of Hamilton than about her missing fiancé and the circumstances of his leaving her and her newborn.

His absence haunts the memoir, but Nickerson instead draws the now wavy-lined ghost of Nancy wandering the city after her unsolved murder roils the community into action, albeit short-termed and shallow. The memoir does not end with its central conflicts of homelessness and gentrification solved either.

(Drawn & Quarterly)

(Drawn & Quarterly)

It ends with other kinds of even slower personal transformations. Nickerson is expert at cyclical plotting, allowing certain events and images to repeat in a fractured order that offsets the memoir’s “broken” motif of shattered windows and emotional lives. She repeatedly returns to a moment preserved in a photo album when she and her fiancé were still together, posing with her parents before a scenic background. Though Nickerson reduces the scenery to nearly nothing, she draws her own suddenly detailed fingers holding the image, as if removing the panel from the layout to examine it more closely.

What does it mean that the implied author looking down from the reader’s God-like vantage isn’t the same blob as the “photograph” of her? I’m not sure, but it’s that kind of emotional thought experiment that underpins all of Nickerson’s vague yet-not-vague creation.

Ultimately the version of herself she portrays near the end of the memoir is a healthier version than the one at the beginning. They are also literally the same. Nickerson repeats the images of the opening pages—a blob mother changing her blob son’s diapers, giving him a bath, reading him to sleep—changing only the narrated words superimposed at their margins. She begins with the realistic but socially taboo complaints of an overtaxed mother missing her former professional life.

By the end, that same mother is cherishing those identical moments, aware of how quickly they are passing. The effect is not that this new wisdom overwrites the earlier struggles, but that it exists with them simultaneously.

Perhaps parenthood is a little like James Street, an imperfect place filled with struggles and rewards and no clear end in sight.

- sylvianickerson (@sylvianickerson) | Twitter

- Creation by Sylvia Nickerson - Book Launch

- creation poster – Sylvia Nickerson

- Creation: Sylvia Nickerson: 9781770463776: Amazon.com: Books

- Sylvia Nickerson | Drawn & Quarterly

- Sylvia Nickerson (@sylvianickerson) • Instagram photos and videos

- Creation | Drawn & Quarterly

- Sylvia Nickerson