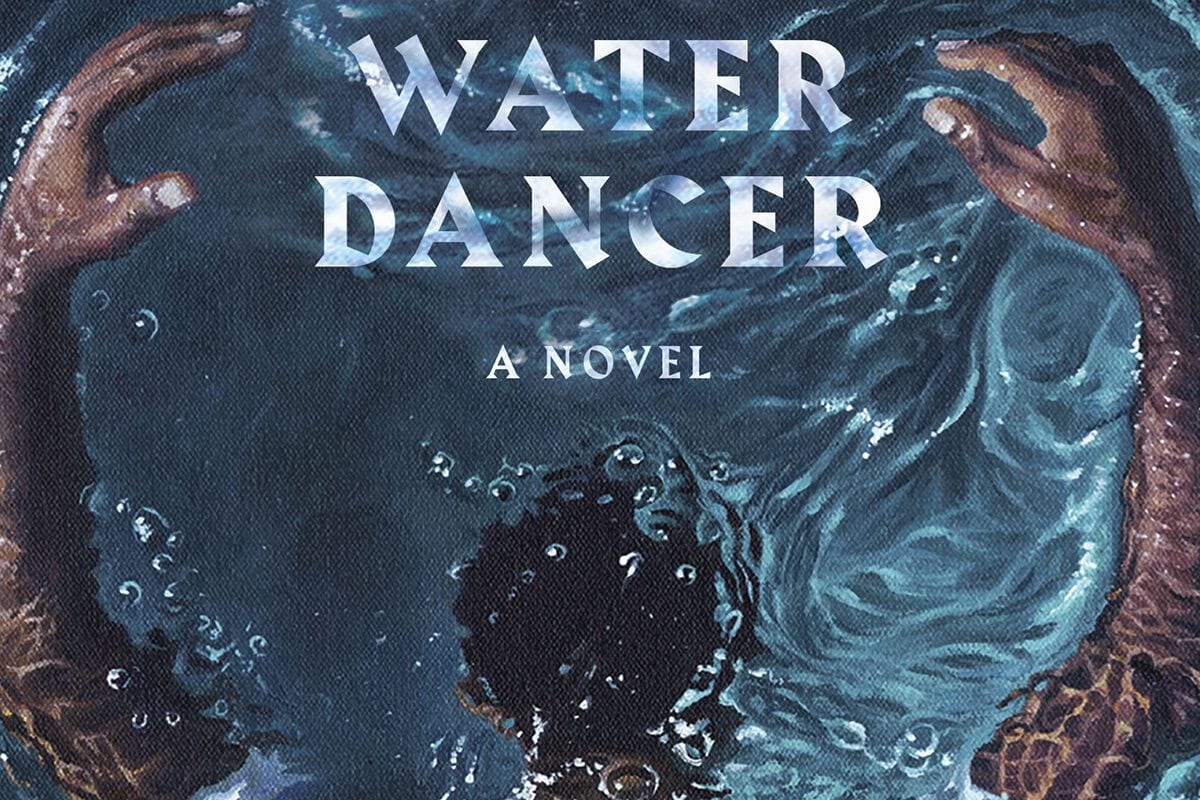

After years of proliferating influential essays, Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ offers an accessible, intelligent work of historical fiction with fantastical elements in his debut novel, The Water Dancer (2019). Coates builds upon recent and traditional African American literature while succeeding in mixing genre. He stays loyal to his characters and through evocative language, utilizes genre elements to elevate his key themes: the importance of memory and the discernment needed to define family fluidly in the struggle created by the institution of slavery.

In

The Water Dancer, Coates uses a poet’s prowess to invent a lexicon of proper nouns that recast the slave narrative. Slaves are referred to as “The Tasked”, slave masters are “the Quality”, the slave catchers are “The Hounds” and so forth. These terms not only delineate Coates’ universe in a memorable way; they are pregnant with thematic meaning and reinvigorate a discourse that has become familiar, and perhaps evening tiring, to some Americans.

Like a slave narrative, the novel’s chief subject is its narrator, Hiram, illegitimate son of Virginia tobacco baron, Howell Walker through one of his slaves, Rose. Walker sold Rose off for unknown reasons, wrenching her away from Hiram when he was only a boy, the traumatic event leaving a bedeviling lacuna in Hiram’s disconcertingly perfect memory. Hiram describes it this way:

“My mother was the best dancer at Lockless, that is what they told me, and I remembered this because she’d gifted me with none of it, but more I remembered because it was dancing that brought her to the attention of my father and thus had brought me to be. And more than that, I remembered because I remembered everything—everything, it seemed, except her” (4)

Unlike a slave narrative, The Water Dancer opens en media res with Hiram chauffeuring his carousing, lackluster half-brother, Maynard, home from a soirée. Suddenly Hiram sees a spectral image of his mother dancing on the very bridge over which she was carted away. Inscrutably, the vision sends Hiram plunging into the river below.

The novel’s inciting incident is one of Hiram’s early experiences with his second superpower, teleportation, referred to in the novel as Conduction. Hiram’s first experience of Conduction feels like the Middle Passage in that its suffocating, against his will, and it nearly drowns him (6). Octavia Butler’s Kindred (Doubleday, 1979) is about a character cursed to time travel back to slavery days at inopportune moments outside her control. The Water Dancer‘s plot is the inversion of this.

Hiram’s endeavor to master his power animates his character arc. Alhough such an arc is akin to a superhero origin story, Coates executes the premise literarily by connecting Hiram’s Conduction power to his other quests: fleshing out his memory of his mother and forming for himself a family out of a patchwork of people who recognize his true quality.

After recovering from near-drowning, Hiram is tended to by Sophia, his Uncle’s concubine. Hiram develops feelings for her and eventually the two make a desperate escape that leads Hiram on a journey north, where he’s befriended by abolitions for the Underground Railroad. In their company, Hiram finds camaraderie, but must still grapple with who is family and who isn’t.

Compared with other contemporary novelists who use alternative forms and multiple points of view, Coates’ toolbox might seem small. But through Hiram and his adventures, Coates uncovers an uncomfortably clear looking glass for America’s history and current time.

In the depiction of Walker, Coates incarnates Toni Morrison’s idea put forth in Playing the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1992), in which she posits that racist whites without slaves to domineer dissolve into ineffectuality and incoherence. Walker prefers to nurse falsehoods about his white son Maynard’s abilities, rather than see Hiram’s inherent worth and potential; to acknowledge Hiram as the obvious choice as inheritor of his business would be to admit the hollow conceit of race underpinning Walker’s crumbling world. Yet Coates approaches Walker not with a tone of animosity but gentle pity.

As Hiram navigates pro and anti-slavery circles of powerful whites, Coates depicts scenes that seem to excavate the roots of today’s white fragility and clandestine feelings of racial superiority that hide in the hearts of moral crusaders. As he did in his essay, “The Case for Reparations” (Atlantic Magazine, June 2014), Coates uncovers hidden histories whose revelations give credence to the idea of black genocide. During the unearthing that occurs in The Water Dancer, Coates doesn’t preach or condemn, but entertains and informs, illuminating the African folklore that shaped early African American life in which culture proliferated despite bondage.

The Water Dancer’s spiritual mother is Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (Knopf, 1977), but Coates’ structure lacks Morrison’s inventive leaps in time that keeps us riveted, as if we’re watching a piece of performance art. Coates writes long, giving us play by plays of Hiram’s days where a more seasoned novelist might have summarized or omitted some of the over 400-page narrative. In addition, the characters all seem to know Hiram is the main character; they offer him unsolicited advice or information and confirm things he was just thinking, rendering portions of the dialogue to read more like a roleplaying game. But whereas Morrison’s Song of Solomon core image is doomed flight, The Water Dancer soars as a triumph as readers piece together Hiram’s lost memories and discover how he learns to dance.