The Sentimental Journey of John Lennon’s “Imagine”

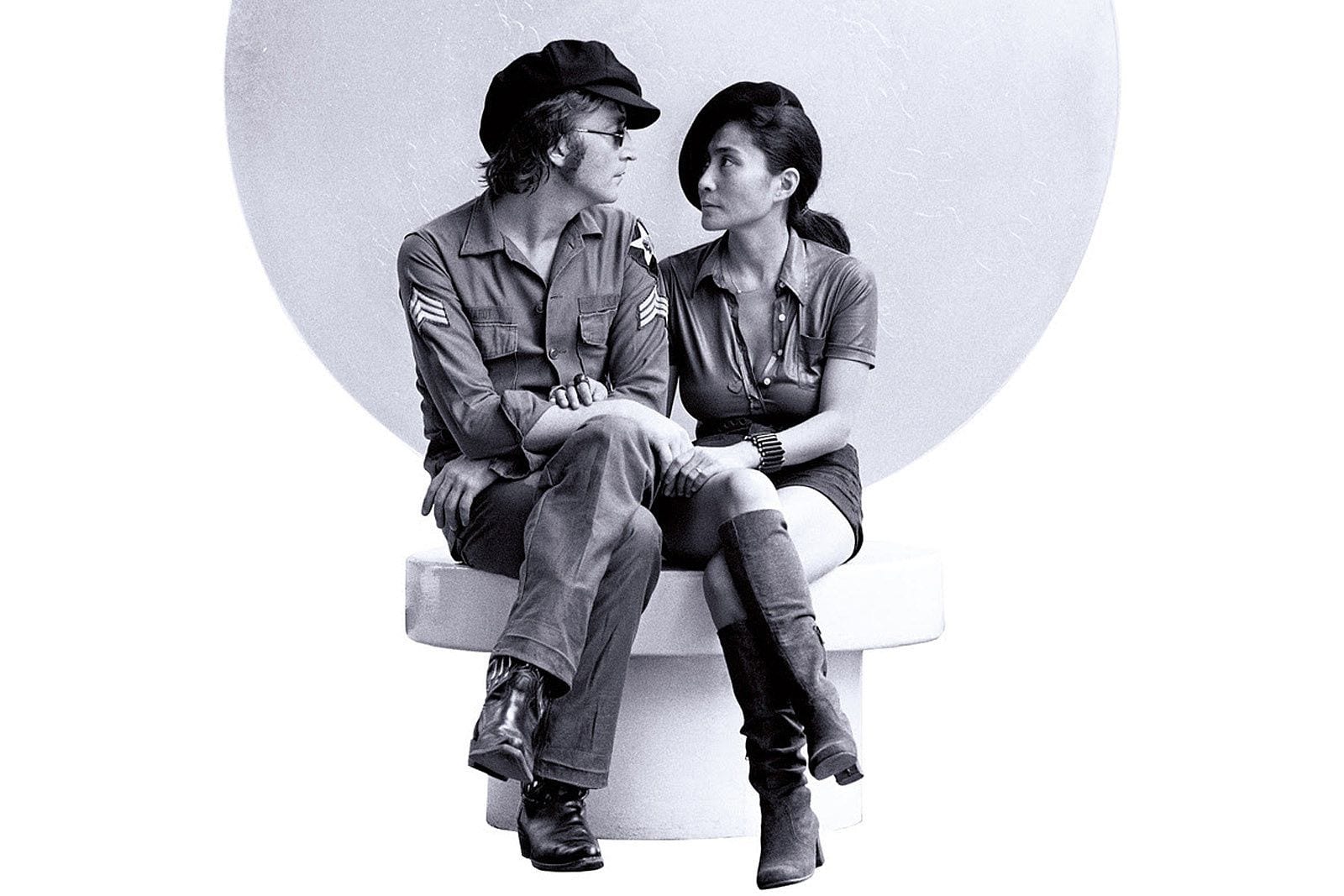

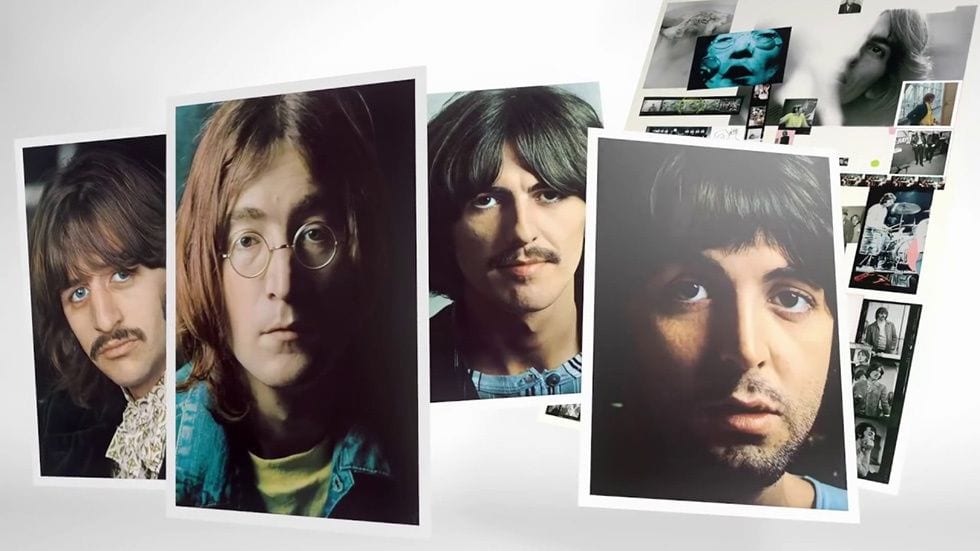

For many growing up in the 1960s, the Beatles‘ revolutionary music grew into revolutionary passion as the decade progressed. Although John Lennon became an icon of peace and love, glorified in popular culture through events like the “bed-in” for peace as much as his martyrdom by senseless violence, his place in the music scene was more revolutionary and incendiary than Middle American.

The “more popular than Jesus Christ” comment is only one pop culture example of how Lennon could attract global public attention with his message. Yet this message often made even his ardent followers a bit uncomfortable, not only by how the message was delivered but because it would require them to actively change their lives — and the direction of global politics. Many people revere their idealized version of John Lennon, but few today seem inclined to take his political message to heart.

The same is true of Lennon’s iconic song, “Imagine”. In the decades since his death, “Imagine” ironically has become associated not with revolution or anti-establishment protest, but with the warm fuzziness of a comfortable dream that increasingly is beyond our grasp. Its lyrics proclaim revolutionary concepts: a world without religion, humanity without the constrictions of borders and politics’ marriage with big business, no capitalist dream of greater production/profits coming from greater consumerism. Instead, Lennon’s vision seems increasingly simplistic and unattainable today, although even in 1971, it promoted a radically different reality than that found in the UK or US.

Among its many “uses” in popular entertainment outside the music industry, “Imagine” has been featured during the most poignant moments of beloved television series that celebrate Middle American values – late 1980s/early 1990s Quantum Leap and Glee – as well as the televised celebration of each new year in Times Square, an annual rite of hopeful penance and temporary banishment of cynicism.

“Imagine” a World Without War

In 1990, science fiction television series Quantum Leap broadcast an episode that would become one of the fans’ favorites and perhaps one of the most emotion-rending moments on television fiction. Even years later, fan forums and lists of favorite episodes include “The Leap Home, Part 1”, in which time traveler Sam Beckett (played by Scott Bakula) leaps into his teenage self and tries to right wrongs within his own family.

The leap takes place in 1969, during the last Thanksgiving the family would have together before Sam’s brother is deployed to Vietnam (a tour of duty during which he is killed). The series’s prevalence of war and its horrific separation of families is a recurring theme. In this episode, Sam naturally wants to save his brother from death on the battlefield. “War” is implied in another terrifying future scenario for adult Sam; his younger sister will someday face domestic violence from an abusive partner. Violence, separation, and death are often associated with war, whether on a foreign field or behind locked doors. Sam tries to imagine a future for his family without such strife.

A primary reason why this episode strikes such a sentimental chord among fans of all ages (who watched first-run episodes or enjoyed reruns or DVDs years later) is the use of “Imagine” to connect Sam with younger sister Katie (Olivia Burnette) emotionally. Pippa Parry, the webmistress of long-running, still-popular Quantum Leap fansite, Project Quantum Leap, explains why this song meshed beautifully with the television series’ philosophy and why, through Sam, “Imagine” is the perfect theme.

“Sam is the epitome of goodness and kindness, always trying to do the right thing and help people as much as he can. [He] reminds us all of what the human race could be like if we would all pull together.” In this episode, “Sam wanted desperately to please everybody; he wanted to save his brother from being killed in Vietnam and his father from having a coronary, and he also needed to reassure his little sister that her favorite Beatle (Paul) wasn’t dead. He nearly gave the game away by starting to say that it was John who was dead in the future, but Al stopped him just in time, so he went on to say that John wrote his favorite song, ‘Imagine.’ I’m sure this song evokes feelings in everyone who hears it, and for Sam, it had great meaning because he so wanted everything in his family’s life to be perfect.”

On 28 September 1990, when “The Leap Home, Part 1” was broadcast, the tenth anniversary of Lennon’s death was only a few months away. Because the “leap” took place during Thanksgiving 1969, the family-oriented holiday and theme of being thankful added special emphasis to the hopeful nature of “Imagine” as a generic wish for peace, not an anthem for radical sociopolitical change. Like so many Americans of his generation, Sam latched onto “Imagine” as a personal anthem, a motivational song by which he would live his life. Sam’s purpose for leaping through time was to “make right what once went wrong”, indicating his ability to imagine a greater future for others, even at the price of personal sacrifice.

Although this episode underscores Sam’s need to re-imagine his family’s future, it also illustrates that the reality of what we can imagine often is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Quantum Leap sentimentalizes the song but highlights that to attain world peace, we need to do more than just “Imagine”. As Parry notes, “Unfortunately [Sam] ended up making his sister cry and realizing that he couldn’t re-imagine his life after all — so sad. Just thinking of this episode brings tears to my eyes.”

In the second part of this episode, Sam finds himself leaping into the front lines in Vietnam with yet another chance to save his brother. In later episodes, he continues to fight against oppression and violence to bring about a more enlightened, peace-promoting world. Sam continues his “activism”, even though he realizes that changing the world is a difficult, often thankless commitment.

The sentimentalism of “Imagine” in a series that promoted peaceful activism and the desire to help others improve the future nevertheless was tempered by the lead character’s difficulty in making reality fit the dream. In a small way, Lennon’s revolutionary theme within “Imagine” was kept alive — those who believe in the future described in this song need to act to make this vision real. Quantum Leap fans today, however, mostly recall their emotional response to a well-acted scene emphasizing family’s importance.

The 2009 use of “Imagine” within the television hit Glee indicates how much the song has become further sentimentalized but less activist during the intervening two decades since “The Leap Home”. Again, “Imagine” frames holiday sentiments surrounding Thanksgiving, whether a holiday being celebrated on screen or by the audience watching an episode. Ironically, “Hairography” was broadcast on 25 November 2009 — 40 years after the “leap” date of Sam’s Thanksgiving visit home. (Yet another bit of Quantum Leap trivia: John Lennon and Scott “Sam Beckett” Bakula share a 9th October birthdate.) On Glee, however, opposition to war/violence isn’t the predominant theme supported by “Imagine” — equality in social status or individual acceptance is emphasized.

The Haverbrook Deaf Choir begins to sing “Imagine”, but the New Directions glee club (the series’ stars) interrupt, an action that bothered some television critics. Liz Purdue wrote in her Zap2It review: “The deaf students perform ‘Imagine’, with sign language and one student talk-singing until Mercedes and the rest of Glee Club join in. Or should I say butt in? It’s lovely, and I understand the symbolism, but isn’t it a little insulting for them to just take over the other students’ performance?” Alden Habacon’s Schema review, however, called this musical moment “groundbreaking TV” because the deaf choir succeeded in “stealing the show [with] the heartfelt rendition of John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’.”

Although critical reactions to this scene were mixed, “Imagine” serves as a way for the deaf students — and eventually the multicultural New Directions singers, many who also face discrimination as a sociopolitical minority — to envision a category-free world. Glee re-imagined “Imagine” to fit its own sentimentalized purposes, but the episode had a powerful positive effect on many fans who watched that scene. As one blogger posted on Forum DVD Talk shortly after the episode ended, “That’s the second time “Imagine” got that kind of reaction from me by a TV show. The first was Quantum Leap.”

By 2010, “Imagine” had become the go-to song to evoke a positive emotional response to a variety of causes or, more generally, to the need for global improvement. As broadcast by cable and national networks, the annual ritual of New Year’s Eve in Times Square further cements “Imagine” as the all-purpose sentimental wish for a peaceful, prosperous future. The loudspeakers throughout Time Square play “Imagine” close to midnight, and Lennon’s voice can be heard above the revelers and stage performers – even over network announcers.

Audiences have become attuned to listening above all the noise for “Imagine”. It introduces the countdown before the ball drops – and another year lands heavily upon the crowds cheering in New York and watching from around the world. Replacing Guy Lombardo’s rendition of “Auld Lang Syne”, John Lennon’s “Imagine” has become a holiday tradition. Audiences don’t have to do anything; they merely can cheer the sentiment, and their resolution somehow to help create a better tomorrow most likely goes the way of most New Year’s resolutions.

Whether Thanksgiving or New Year’s, television, or real life, “Imagine” has become synonymous with heart-tugging emotion and, increasingly, a wistful desire for a better future. No one seems to mind that Lennon’s meaning has been co-opted for an ever-widening range of causes or watered down to a general desire for something better.

The Fatal Flaw of “Imagine”-ing

Perhaps “Imagine’s” fatal flaw that makes it irresistibly attractive as a national anthem or hopeful plea for a more generalized peaceful future is its gentle tone, singable range, and quiet approach. Through a simple tune and quiet delivery, Lennon can still lull the populace into thinking that his radical ideals are not only desirable but possible. He ensnares a wide audience in his musical net with the line, “I hope someday you’ll join us.” That inclusiveness hints that Lennon has/had the answers for those post-1960s flower children joining the workforce and, decades later, their children and grandchildren looking for a better tomorrow.

Of course, the better tomorrow Lennon envisioned vastly differs from the wishes of increasingly stressed out, technologically left behind, cash-depleted masses who long to be some of the “haves” rather than the “have nots”. Lennon’s lyrics portray the bliss of having fewer or no possessions; that reality is not perceived as blissful in the current global climate. Such disconnect between Lennon’s lyrics and languid melody is mirrored today by the continuing popularity of “Imagine” as an idealized, romanticized vision of the future versus its original message.

Even Lennon recognized the discrepancy between his meaning and the song’s popularity. In Lennon in America: 1971-1980, Based in Part on the Lennon Diaries, author Geoffrey Guiliani quotes Lennon noting the irony of “Imagine”‘s popularity. Lennon called “Imagine” an “anti-capitalistic” song, adding, “Now I understand what you have to do. Put your political message across with a little honey… Our work is to tell [apathetic young people] there is still hope and still a lot to do.”

The honeyed vocals of “Imagine” still inspire sweet sentimentality, but the song’s effectiveness as a revolutionary call to action has become muted over the decades. Whereas even in a memorable 1990 Quantum Leap episode Sam’s desire to change the future accompanied an emotional on-screen moment, more recent uses of the song emphasize hope and emotion over an active agenda for sociopolitical change. Lennon’s political message is losing ground, even as “Imagine” becomes further entrenched in American popular culture via television episodes and events.

Through “Imagine”, John Lennon’s legacy may become a permanent part of popular culture, not just of music or even political history and culture; however, its use on US television, through such idealistic mainstream fiction as Quantum Leap or Glee, as well as co-optation for sentimentalized public events like New Year’s Eve celebrations, ultimately may shift “Imagine” from an anthem for change to a dream that stands little chance of being realized. Consequently, it distances public perceptions of Lennon ever farther from his real role as an instigator of sociopolitical change.

***

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on 16 November 2010. Minor updates have been made.