Liz Phair

Liz Phair: self-titled

Back in 1993, Liz Phair’s debut album Exile in Guyville shook indie rock music to the core. An instant classic, the album was an astonishing blend of slick guitar rock, artsy lo-fi, folk, and pop, fueled by Phair’s assured, confident, daring, profane, and endlessly witty lyrics. Phair, who hailed from suburban Chicago, sang in a charmingly flat, cracking voice about “standing 6’1″ when I’m 5’2””, roommates who left “suspicious stains in the sink”, shallow young men (“Soap Star Joe”), and horny young women (“Flower”). The album’s title was a blend of The Rolling Stones’ classic Exile on Main Street album, and the song “Goodbye to Guyville”, by fellow Chicago rockers Urge Overkill, and it was the perfect title, as Phair, all 5’2″ of her, broke loose from the “Guyville” of the Chicago rock scene, leaving all the hard rock dudes in her wake. Her claim that the record was a song-by-song response to Exile on Main Street, while not entirely true, was a self-promotional masterstroke, and as a result, the press started to take notice. Like an early ’90s Patti Smith, Phair’s candor and in-your-face stance was a breath of fresh air, as she won thousands of new fans, women and men alike.

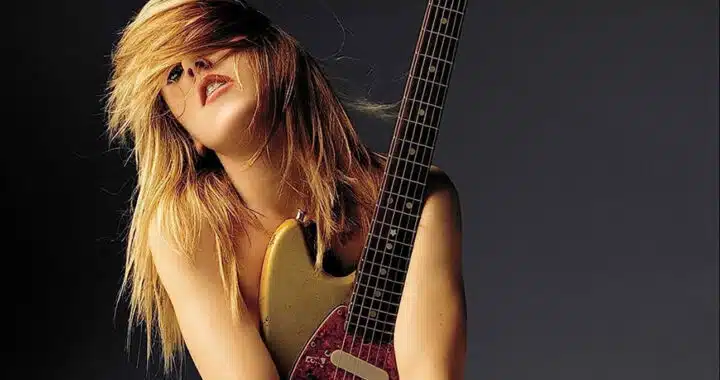

Now fast forward ahead ten years. Liz Phair now has a mere four albums under her belt, and today, this once-adored darling of indie rock is a mere shadow of her former self. She’s left Chicago, gotten divorced, moved to Los Angeles, has taken singing lessons, and has employed some high-priced teen pop producers to help her sell albums. The resulting album, Liz Phair, is a highly overproduced, shallow, soulless, confused, pop-by-numbers disaster that betrays everything the woman stood for a decade ago, and most heinously, betrays all her original fans. In contrast to her of her infamous, audacious “flashing” cover photo for Exile in Guyvile, Phair’s new album cover has her sitting, legs spread-eagled, a guitar placed suggestively between her legs, her hair stylishly tousled, looking like a cheesy Maxim photo shoot. It’s an album by a woman who has completely lost touch with what made her music so great in the past; Ms. Phair has never been one to shy away from speaking her mind, and her new record is nothing more than a hearty “fuck you” to everyone who bought her first two albums, as she tries to become the next Avril Lavigne. Only, she fails at that, too, in spectacular fashion.

How did it ever come to this? Well, although her career output has been less than prolific, her music has been taking a gradual downward turn since her debut. Phair’s sophomore 1994 album, Whip-Smart, wasn’t quite as consistent as Exile in Guyville was, but it still had plenty of Phair’s songwriting smarts to save it. Produced by Brad Wood, who was also at the helm on her debut, Whip-Smart had a similar lo-fi feel as its predecessor, but with inventive pop touches throughout, on such songs as “Supernova”, “Whip Smart”, and “May Queen”. After that, it was another four years until we heard from Liz again, and whitechocolatespaceeegg, her 1998 debut for Capitol Records, was a much more inconsistent album, and a commercial flop. With four producers, it was all over the map, as Phair sounded like she couldn’t decide whether to go pop or stick to her indie roots. The best songs, like “Polyester Bride”, “Johnny Feelgood”, and “What Makes You Happy”, all produced by Wood, mind you, hinted that Liz Phair was still capable of some magic, but it was obvious that magic was waning.

Liz Phair, like that last album five years ago, boasts a bevy of producers, but this time we know what Liz wants: strong record sales. Wood’s studio wizardry is sorely missed here, as the album’s four producers, which include Phair herself, R. Walt Vincent, Michael Penn, and noted production team The Matrix, apply such a plastic sheen to the music, that any kind of artistic quality is buried deep beneath a thick veneer of artificial, pasted-together, Pro Tools production, and some obviously electronically enhanced vocals.

The producers who have most Liz Phair fans screaming bloody murder are the infamous trio of pop svengalis who call themselves The Matrix. This team, consisting of Lauren Christy, Graham Edwards, and Scott Spock, gained notoriety after propelling the career of Canadian teen Avril Lavigne in 2002 by writing and producing her massive hits “Complicated” and “Sk8er Boi”. They excel at writing and producing one-dimensional, cute, catchy, disposable teen pop music, but as we find out on Liz Phair, while they create some mighty slick kiddy music, they’re not exactly Gerry Goffin and Carole King.

No matter how shallow their music may be, you can’t deny that The Matrix know what they’re doing, and the sickeningly effervescent “Extraordinary” possesses all the characteristics of the team’s trademark sound, such as the usual grungy guitars, the bouncy melody, and plenty of layered, sugary vocals by Phair, which, despite sounding catchy as hell, are some of the most insipid lyrics she has ever sung (“I am extraordinary/If you’d ever get to know me/I am extraordinary/I am just your ordinary average everyday sane psycho supergoddess”). The other three tracks sound just as slick, but sputter: “Rock Me” is more of the same (complete with a ridiculously clunky “baby baby” chorus that would make Poison cringe), as Phair sings in that new little girl voice of hers, about bedding a younger man. Not so bad, but her songwriting has never been more unintentionally hilarious when she sings, “Your record collection don’t exist/You don’t even know who Liz Phair is” (when you take five years to put out a new record, chances are, most young people won’t know you from a hole in the ground). Meanwhile, “Favorite” tries to be one of those trademark saucy Liz Phair songs (“You’re like my favorite underwear/It just feels right/You know where”), but lacks any of the cheeky humor of her early songs. The biggest offender is “Why Can’t I?”, a note-for-note retread of Lavigne’s “Complicated”. Though The Matrix is an outfit with limited ideas, they do what they were hired to do on this album, producing idiotic, cookie-cutter pop, but it’s something we’d rather hear an 17-year-old girl sing, instead of a 36-year-old woman.

Surprisingly, it’s not the Matrix-produced songs, but rather, nine others that make the album even more impossible to bear. “It’s Sweet” has a spectacularly awful Bollywood sound, while “Take a Look” is a flaccid attempt to sound like the post-makeover version of Sheryl Crow. “Little Digger” tries to be sincere, as Phair sings about her son not liking the man who comes home with his mother, but it has a melody recycled from every other folk-lite singer/songwriter, and doesn’t really have anything creative to say (“I’ve done the damage/The damage is done”). “Firewalker” sleepwalks, a drowsy, wavering ballad, and “Love/Hate” astonishingly resurrects the dated riffs of 80s hair metal. Meanwhile, “Bionic Eyes” is a failed attempt at a Clash-like sound, while “Friend of Mine” and the syrupy “Good Love Never Dies” sounds as cliched as the titles indicate.

The worst offender, though, is the song that everyone will likely be talking about. “H.W.C.”, which stands for “Hot White Cum”, tries to continue where “Flower”, “Fuck and Run”, and “Chopsticks” left off, but instead of being a bold, clever statement by a liberal-minded woman, it’s uncomfortably graphic, a pandering attempt to get Phair some notoriety, as she explicitly praises the skin-clearing qualities of her lover’s . . . well, you know. It’s even weirder how a song that could never get played on the radio would be on such an otherwise commercial-sounding album. With its bouncy, acoustic, sing-song melody, and such ludicrous lines as, “It’s the fountain of youth, it’s the meaning of life/So hot, so sweet, so whet my appetite,” you’d think Phair is being sarcastic (if someone like Tenacious D sang this, it would get big laughs), but judging from accounts of her performance of the song at the recent South By Southwest Conference, she’s absolutely serious, going as far as declaring it a statement of female empowerment of some sort, but you can’t get people to take you seriously when you have semen in your hair.

Still, there’s one song on Liz Phair that manages to stand out above all the others. “Red Light Fever” is nothing but another empty pop song with a contagious melody, but if taken as a silly little nugget of radio schlock, and not the last desperate gasp of a soon-to-be-has-been artist, it does its job very well. Producer Michael Penn doesn’t overload the five-minute ballad with bombastic guitars and overdone vocal histrionics; instead, the arrangement is much more simple, and Phair’s singing sounds gentle and restrained. The lyrics are nothing to get excited about (“Lying wide awake in the dark/Trying to figure out where you are/Always going nowhere/Afraid of going somewhere”), but the gently sweeping chorus takes you away, taking your mind off the fact that the rest of this album is a festering heap of aural swill. That’s all well and good, but then you wind up thinking, “Why isn’t Mandy Moore singing this?”

Ten years ago, both Liz Phair and PJ Harvey released albums at roughly the same time; both Exile in Guyville and Rid of Me were astonishingly powerful albums made by two audacious, seemingly like-minded women. Though her music has been toned down over the years, Ms. Harvey is still strong, her albums going in new directions without compromising her respectability, showing she’s unafraid to sing about being happy without getting syrupy. Liz Phair, on the other hand, has grown increasingly more shallow as the years have gone by, and has reached a career nadir with a new album that practically begs to be noticed, simultaneously trying to be controversial and radio-friendly without knowing which to settle for, and ends up being a colossal, muddled disaster. This album just could be her commercial breakthrough (stranger things have happened), but it’s at the cost of what’s left of her integrity. Five years ago, Phair sang, “It’s nice to be liked/But it’s better by far to get paid.” If her longtime fans stop caring after hearing this putrid crap, we’ll see if that’s what Liz still feels.