The Obstacles in ‘Ant-Man and the Wasp’ Are Not Typical of MCU

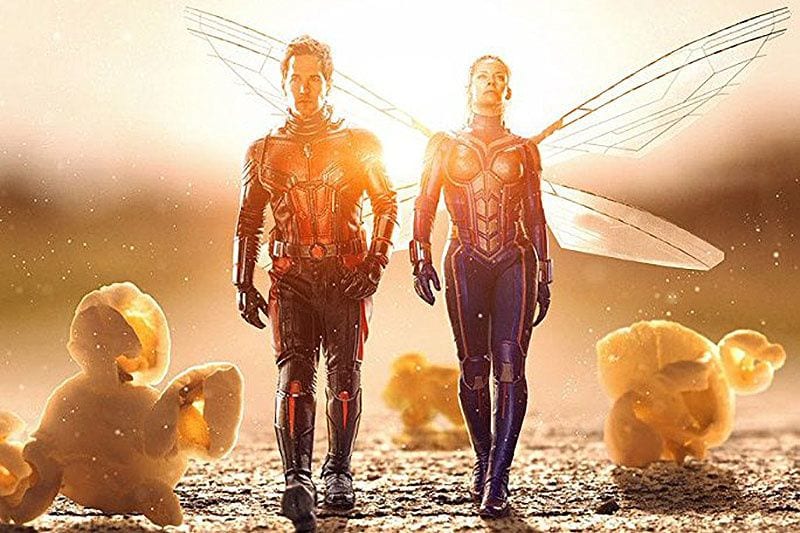

Peyton Reed's "Disney-fied" Ant-Man and the Wasp is unchallenging in all the best ways.

Peyton Reed's "Disney-fied" Ant-Man and the Wasp is unchallenging in all the best ways.

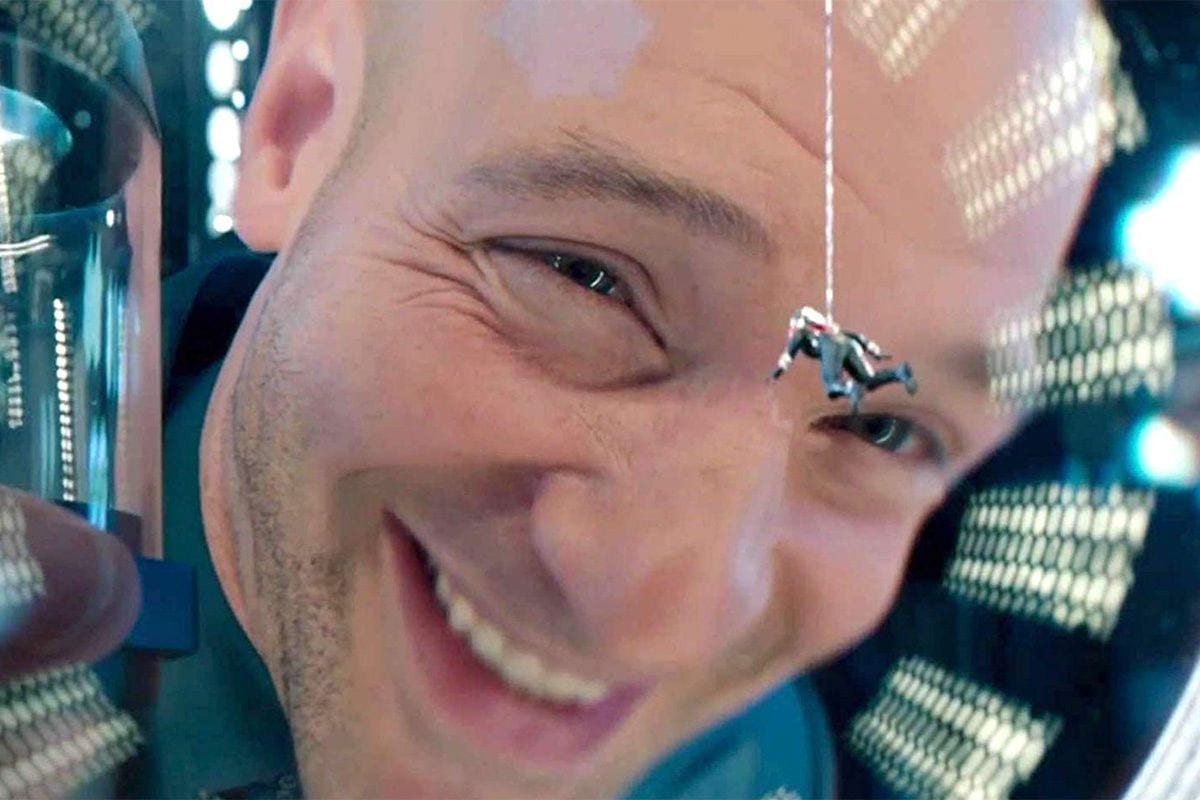

There are strong emotional stakes and likeable characters in Peyton Reed's Ant-Man, but they are all rooted in a, well, less than epic scale. This makes Ant-Man refreshing, an MCU palate cleanser.

Paul Rudd is at the top of his game in Ant-Man and the Wasp, but Evangeline Lilly isn't given an equal platform, despite what the title suggests.

Peyton Reed's campy follow-up to the epic Avengers: Infinity War serves as a welcome breather from saving the world.

Show-stopper

I do parts based on what speaks to me and what I feel I could do a good job at. This just happens to be that.

— Jennifer Aniston, Entertainment Weekly (26 May 2006)

Beware the meet-cute at a Cubs game. Much as Gary (Vince Vaughn) and Brooke (Jennifer Aniston) are clearly not meant for one another, and much as he appears to think they are exactly that, the start of The Break-Up is all about the hook-up. He’s with someone named Johnny O (Jon Favreau), she’s with a nameless other guy (whom he aggressively labels “the guy with the tucked-in stuff”), and he buys her a hot dog, encouraging her to take it with “a condiment.” “You’re crazy,” she observes. And that, more or less, is that.

The opening credits still-photos montage tracks the brief and ostensibly intense trajectory of their romance, as they make photo-booth faces, join a bowling club, attend a costume party dressed as cows, kiss in the rain, kiss near a Christmas tree, and kiss in bed (who’s taking this snapshot is not clear). They smile, they cuddle, they gaze. They look rom-comically content, if not precisely appealing. They buy a condo.

Then comes the kibosh indicated by the film’s title, ostensibly brought on by an utterly mad dinner with parents and siblings. This even though it’s clear from their first actual scene in the condo exposes the contrivance of the relationship and the fight, that actually begins before the relatives arrive, as Gary, a Chicago tour bus guide in business with his slouchy brothers, is obviously and oh so odiously Brooke’s opposite that you can’t help but wonder what that opening montagey business was pretending. Their conflict is drearily familiar: he’s a resentful perpetual adolescent and she’s an upscaley art gallery manager who wears perfectly tailored designer outfits and a spectacular haircut. They’re types and the film doesn’t have a new thing to say about them.

On the night of the break-up, she’s preparing dinner, awaiting Gary’s arrival after he’s spent a long day on his feet, telling tourists what to see. The fact that she’s also been on her feet seems not to enter onto Gary’s radar, who slumps himself onto the couch and sets up to watch sports (and no, apparently he can’t be any more original than that). Immediately, he fails her (he brings home the wrong number of lemons) and she claims he doesn’t appreciate her. It’s not as if this particular conflict needs to be repeated, as it is the typical rom-com conflict, but The Break-Up brings a grim vehemence; if not innovative, it is unusual for a movie termed a “comedy.”

Just so, Brooke and Gary take up newly militant residence in their respective condo corners: she claims the bedroom, he the living room with convertible sofa (no sheets for him, but he’s a guy who doesn’t care about such niceties). Their choices of battles hardly seem sane (this presumably attributable to irrational rage roiling between them), but more to the point, they’re not very interesting. He tends to perform Vaughn’s patented motor-mouth disparagement routine, hitting buttons sure to infuriate Brooke (her gratingly intense, a-cappella-group-singing brother Richard [John Michael Higgins] is “gay,” which she can’t see, her sister’s promiscuous — just why these zings affect Brooke so severely is unclear). Without similar resources (she’s no Rosalind Russell), Brooke takes the apparently only other option: she schemes like a screwball comedy heiress might, though without the sweet energy or delirious abandon.

Gary’s first all-out assault involves territory (no pissing, but you get the idea): he purchases the pool table he’s always wanted and she refused to allow into her precisely feng-shuied space, invites his friends (including Jason Bateman, mostly looking confused) for cigars and beers, and plays loud boy-rock. She comes home from work, turns her smile upside down, and retreats to her room, where she cranks up her Alanis Morissette. Brooke’s most frequently used tactic is, in fact, frowning. While it’s not a very effective strategy, it does mean that she spends most of her movie looking unhappy.

And no wonder, for Brooke’s responses to Gary tend to be derived from advice she solicits from her happily married/mother of two best friend Addie (Joey Lauren Adams) or her employer Marilyn Dean (Judy Davis), a haughty gallery owner who is stereotypically self-absorbed and humorless. Addie observes that men are like children who “test boundaries,” Marilyn Dean (who refers to herself in the third person and by both names) comes up with the show-stopper: she sends Brooke to her spa for the “Telly Savalas.”

After a brief, pert rip-off of The 40-Year-Old Virgin‘s painful-grimace-during-waxing scene, Brooke returns to the condo in order to show off her new visible pudenda (Aniston’s naked walk from bedroom to kitchen and back — with crucial areas blocked out by Vaughn’s head and other objects, generated early “buzz”). Gary looks suitably impressed, and the scene cuts to another. That is, the show stopped, and then, it goes on, as if that whole Telly Savalas thing never happened. (It’s just as well.)

Gary’s movie is equally erratic and episodic. He has a few advisors, namely Johnny O and his brothers, with whom he is in the bus tour business, anxiously ambitious manager Dennis (Vincent D’Onofrio) and the swaggering, bizarrely named mechanic Lupus (Cole Hauser). The latter considers himself a ladies’ man, though his effort to show Gary the ropes at a nightclub (which he insists is “stacked with top-shelf dumb-ass”) reveals that his moves are retarded and his eyebrows odd. Johnny O — usually in the bar he tends — makes acute-seeming observations (“She hurt you,” or, later, the reverse, “You never let your guard down, that poor girl never had a chance”) but Gary remains pretty much in the dark, and oh yes, miserably self-absorbed. (This most visible in a scene where he invites buxom girls who don’t speak to play strip poker at the condo: the resulting image — Gary seated on the couch in his boxers with a bottle of booze — is so sad and mean, you wonder if it’s supposed to be in yet another movie).

For all that goes wrong with The Break-Up, the most compelling question it raises has little to do with Gary or Brooke. It also has little to do with Vaughn and Aniston (though some viewers will wonder why she’s paid so much money to pursue projects that “speak to” her). The question has to do with the state of the romantic comedy during a cynical, prepackaged, reality-tv moment. Can this film be made in a way that’s new, or at least new-like? While last year’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith offered an entertaining answer in the genre mash-up, for most often the rom-com per se appears stuck in one gear, where boys must grow up and women must be patient. It’s past time to move on.