richard fleischer

Richard Fleischer’s ‘Trapped’ Escapes from Noir Obscurity

For a few years now, the Film Noir Foundation and UCLA Film and Television Archive have been rescuing and restoring noir films that have fallen into obscurity or devolved into eyesore copies in the public domain. Richard Fleischer’s 1949 Trapped is the latest beneficiary of their attention, and it’s an eye-opening little curiosity for several reasons.

The film belongs to the era’s trend of semi-documentary noirs, full of location shooting and stentorian narration about the efficiency of government and law enforcement. Eagle-Lion Films made a string of such pictures, including this one. In fact, its heroes are “T-men” from the Department of the Treasury, as in the studio’s recent hit, Anthony Mann’s

T-Men (1947). For this follow-up “T” title, producer Bryan Foy borrowed an up-and-coming young director of B noirs at RKO, Richard Fleischer. He’d proved his efficiency with Bodyguard (1948), The Clay Pigeon and Follow Me Quietly (both 1949).

After more than a decade of working up from uncredited bits to supporting roles, Lloyd Bridges got the chance to shine in a starring role as unregenerate slimeball Tris Stewart, who is among the most amoral self-centered leads in noir. Therefore, what happens to him, or rather what doesn’t, is part of this movie’s several surprises as it plays with the structure of the plot and the audience’s expectations.

Similar to other semi-documentaries made in cooperation with official agencies who get thanked in the credits, this movie begins with a narrator’s lecture on the Treasury Department and real-life footage on how money is made and how impossible it is effectively to counterfeit. One of the minor revelations here is how roomfuls of women were employed to sort through the cash.

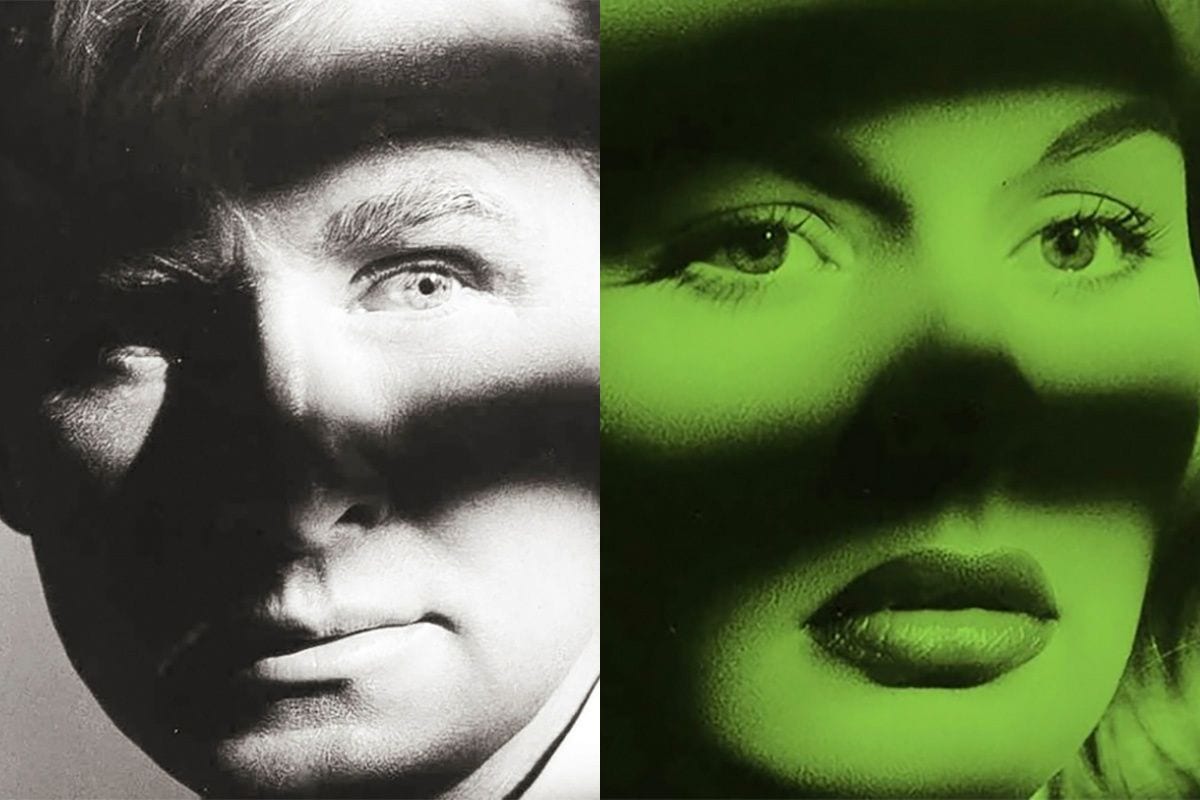

John Hoyt as John Downey and Lloyd Bridges as Tris Stewart (IMDB)

After the pep talk, the story opens on a scene of a hard-working woman who runs a small business. To her dismay, she discovers that one of her $20 bills is a clever fake. The smiling bank teller says that it’s practically her fault for not knowing how to spot it.

The scene shifts to a prison where Tris is doing time, having traded in bills from these same plates. He’s uncooperative with the Treasury investigator, who strongly implies that Tris should play ball in exchange for a quicker parole. This is when the movie goes from straightforward diagrams to tricky double-crosses that keep the viewers on their toes, for the next scene finds Tris handcuffed to a guard on a bus. Tris is being transferred to another prison, but when he spots an apparent confederate driving alongside, he lifts the guard’s gun and makes his escape.

Or does he? The film immediately reveals that all this is a set-up by the federal authorities to fake a prison escape so that Tris can track down his old associates. With his own ideas, Tris pulls his a fast one and really does escape. He hooks up with his old girlfriend Laurie (Barbara Payton), a jaded cigarette girl and hardboiled blonde in a Los Angeles nightclub. Or does he? We’ll stop asking that question or describing the plot, because Trapped has got wheels within wheels that viewers should discover fresh.

A third wheel is provided by a dapper mob-connected stranger (John Hoyt), and also in the mix are James Todd and Douglas Spencer as old associates of Tris’s. The narrative keeps redefining who’s got the upper hand and who knows what’s going on. Trapped is like a chess game in which the factions try to be several moves ahead of each other while crossing each other up. We viewers go from being hoodwinked to being the most informed as we observe the maze of ironies.

As with his other noir melodramas of the time, Fleischer keeps the pace punchy and the fistfights crunchy. One fight occurs within a claustrophobic hotel room that looks the width of a shoebox and the other happens at the beach with obvious stunt doubles who briefly puncture the illusion. Guy Roe’s photography indulges in dandy moments of chiaroscuro so beloved in the genre, especially in the climactic battle on location at the streetcar station.

Barbara Payton as Meg Dixon and Lloyd Bridges as Tris Stewart (IMDB)

Bridges is excellent as a menacing bulldog with a short temper and endless depths of shallowness. He’s matched by a multi-dimensional and believable Payton at the beginning and almost the end of her career as a Hollywood starlet. Her unfortunate life, which resembles a noir tale, is discussed in Alan K. Rode and Julie Kirgo’s commentary and the brief making-of in Flicker Alley‘s Blu-ray. The details have been recounted in several books, beginning with her own tell-all memoir I Am Not Ashamed (1962, 2016 reprint by Spurl Editions), and include an inflammatory relationship with Tom Neal of Edgar Ulmer’s Detour (1945) that effectively ended both of their careers. Ulmer would cast her in Murder Is My Beat (1955).

Trapped marked the start of Fleischer’s collaboration with writer Earl Felton who, according to the commentary and interviews was quite a character and whose Fleischer noirs would include Armored Car Robbery (1950) and The Narrow Margin (1952). The latter employs a fake-out twist not a million miles removed from Trapped. Felton’s novice co-scripter on Trapped is novelist George Zuckerman, who went on to three scripts for Douglas Sirk, including Written on the Wind (1956) and The Tarnished Angels (1958).

One thing about Trapped that may baffle viewers, and which we can’t discuss directly, involves the removal of one of the crucial characters while there’s still 20 minutes left in the movie. The commenters, along with Eddie Muller in an extra, speculate about the unknown reasons for this. While it’s true that this unusual decision clashes with every other noir and even every other mainstream movie, it fits a narrative that consistently sets up audience expectations only to pull one switcheroo after another. This anomalous nature is part of what makes the picture so intriguing.

As always seems to be the case, even the most forgotten noirs offer something tasty when we can look at a good print. Despite a few inescapable blemishes on the 35mm collector’s print that was donated to Harvard Film Archive, this restoration is as sharp as everyone’s outsized lapels and as crisp as the tilt of their fedoras. It’s good to see a minor picture made with such charm and professionalism.