Despite the hazards that any celebrity faces on social media, Swift has found—particularly through Tumblr—a way to break the fourth wall between stars and “stans” by establishing personal, one-on-one relationships with her most ardent followers. One could take a cynical view of this practice, labeling it just a more targeted branding strategy rather than a display of genuine interest in young people. Observing these interactions over time, however, I detect Swift’s very real passion for connecting with—and learning from—their lives. But Swift, always the savvy businesswoman, eventually monetized her online following, launching a gaming app called The Swift Life in 2017 that, unfortunately, morphed into a platform for hate speech, provoked a lawsuit, and quickly tanked in download ratings. Swift’s online interactions, therefore, invite suspicion for how they transmute something genuine—human interaction—into bids for financial gain. These suspicions about social media parallel longstanding critical skepticism toward pop culture produced for a capitalist market, art made to maximize sales.

As a musician, Swift partly inspired the rise of “poptimism“, a critical trend that took off in the early ’00s, finding some writers abandoning their fealty to “cool” genres like indie rock and instead greeting new music by Britney Spears, Lady Gaga, and Miley Cyrus with a seriousness that would’ve been unthinkable a decade earlier. As Swift migrated from country radio to the Billboard Hot 100, she became the perfect object for poptimist inquiry, in part because she has always staked out territory, hard, on both ends of the authenticity/artifice spectrum. Her songs, particularly the early ones, contain lapidary verses that refract teenage concerns into gemlike observations about heartbreak, loneliness, unpopularity, fandom, and fairy-tale love. Her extensive catalog proves that this songwriting technique wasn’t a girlish gimmick, lightening captured by chance in a bottle. Rather, this lyrical precision runs from her earliest compositions (“Our song is a slamming screen door / Sneaking out late tapping on your window” from “Our Song”) through her most recent (“Your necklace hanging from my neck / The night we couldn’t quite forget / When we decided to move the furniture so we could dance” from “Out of the Woods”).

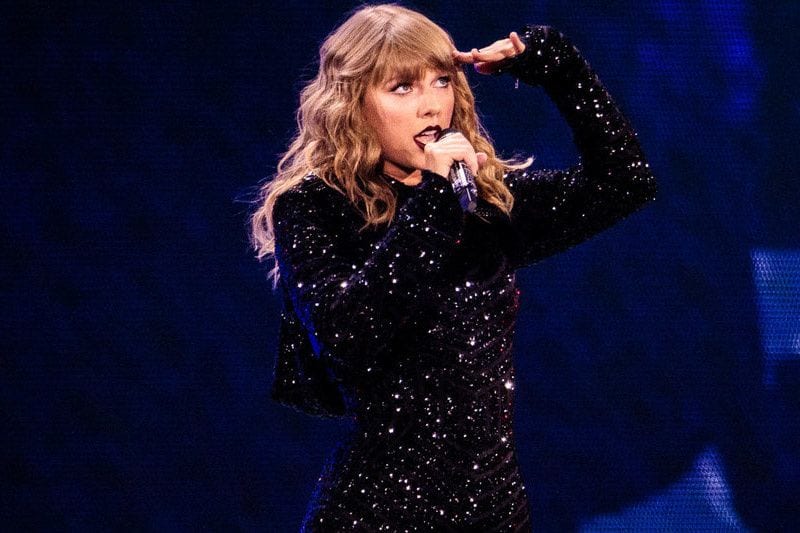

In many of her songs, Swift transmutes the unpleasant dimensions of young adulthood into catchy compositions that young and old alike dance to because they’re sometimes silly, sometimes beautiful, but always extremely effective at beckoning a willing listener into her world. She even mixes giggles and studio chatter right into some of her poppiest songs (see “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” or “This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things”). Like an alchemist, Swift turns stray thoughts and abject emotions into global cultural touchstones—and into piles and piles of cold, hard cash. To take one metric, Billboard estimates that the Reputation Tour will take in more than $400 million by the end of its six-month run.

Behind that cash, of course, lies a marketing strategy: the artifice in Swift’s act that’s grown increasingly hard to ignore. For example, the grin that Swift flashed during “I Did Something Bad” was not spontaneous; it was a highly calculated moment that her band, dancers, and lighting designers had programmed right down to the millisecond. Perhaps that’s what worries some of us about the spell Swift casts on her young fans. She masquerades as their big sister, their cool babysitter, corresponding with them on Tumblr by night while, come daylight, plotting UPS truck takeovers and serving as the official “ambassador” of a rich, white, gentrifying version of New York City. She loves her cats but also gets to carry them on her private jet. She’s a ruthless capitalist in a heartsick, diary-filling, emo teen’s clothing. (Until, perhaps, she donned the dominatrix boots for this tour.)

This precise shift is what inspired my curiosity about her latest tour, for Reputation (Big Machine, 2017) strikes me as her first hard turn away from relatability. (Other critics, such as Lindsay Zoladz of The Ringer, picked up on this theme.) The new material instead represents a narrow slice of life experience with which basically no one else on the planet can identify—save, perhaps, her rival Kanye West. Reputation centers on Swift’s personal battles with fame and criticism, a high-income-bracket soap opera that deserves little more than a fugue played by the world’s tiniest violin, but receives a trap- and house-inspired maximalist treatment that inflates her very specific drama to blockbuster scale. The live show contains some older material, like a medley of “Love Story” and “You Belong With Me” targeting younger fans, alongside the newer, hip-hop-appropriating songs (“Endgame”, “Look What You Made Me Do”) about binge drinking, casual sex, and what Swift perceives to be an epic feud with Kanye West. Throughout this spectacle, Swift seems eager to please; she tries to give something to everyone. Her grab-bag approach to aesthetics reflects, on a thematic level, her commercially safe yet ethically suspect refusal to take a coherent stance toward anything happening in the wider world. And within this refusal, perhaps, lies the reason reputation-era Swift keeps pissing so many people off.

What do we demand of our pop stars in 2018? Swift presents a perfect test-case for a set of questions that have come to define how pop culture gets consumed and evaluated alongside Donald Trump’s frightening rise to political power. Artists must decide whether to address politics or to keep their art insistently separate from it. Are we mere consumers to evaluate entertainment on its political merits, or can we feel okay about ignoring the degree to which an artifact engages the world in which it was made—or doesn’t?

Molly Fischer outlined this concern brilliantly in The Cut, diagnosing our Trump-era pop ecosystem as undergoing a “great awokening”. According to Fischer, fans align themselves with certain cultural documents as a way of signaling their political virtue, and critics risk public shaming, “cancelation”, or at the very least online critique if they appraise a piece of art without reference to its political commitments—or its (shameful) lack thereof. This divide tracks with a conflict that arose among literary critics in the ’80s between two interpretive methods: historicism and formalism. Generally speaking, historicists believe that literature must be considered in relation to its historical and political contexts, while formalists, who date back to the New Critics of the early 20th century, advocate for exclusive attention to a text’s aesthetic properties. As Edward Said famously asked in Culture and Imperialism (1993): Is Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park a fascinating example of the early realist novel, advancing such formal innovations as free indirect discourse, or is it really a book about upper-class Britons’ complicity in the slave trade, since the titular estate Mansfield Park runs on capital that Sir Thomas accrues from a sugar plantation in Antigua? In an ideal world, both readings would be valid and productive, neither blind nor hostile to the other, and Said stands out as a historicist critic whose investment in postcolonial readings is matched by his sensitivity to the aesthetics of literary prose.

It may seem a stretch to place Taylor Swift and Jane Austen under the same microscope. But the historicist / formalist divide, and Fischer’s distillation of our contemporary disagreements over a similar issue, have become as good a predictor as any of whether a listener will like or loathe Swift’s art. The star falls into the formalist-friendly, non-politically-engaged category; one might say Swift embodies it more squarely, and with a larger platform and profile, than anyone else making popular music today. Beyoncé’s work since Lemonade (Columbia Records, 2016) has become increasingly political, while Katy Perry attempted an “awokening” of her own with Witness (Capitol Records, 2017), to mixed results. Lady Gaga, Demi Lovato, and Miley Cyrus have used their platforms to advocate for LGBTQ issues and mental health, and Swift’s tour-mate Camila Cabello delivered a moving speech in support of the Dreamers at the 2018 Grammys, referencing her own experience as a Cuban-American immigrant. This trend suggests that the past few decades—and especially the past two years—have offered plenty of issues on which pop artists can confidently take some moral stand.

Swift, therefore, stands alone as the rare pop star who refuses to risk wading into the scalding waters of Trump-era social discourse. Rather than an activist, she’s a disciplined craftswoman, the musical equivalent of a carpenter sawing away in the woods, building beautiful objects in total isolation. Prioritizing poetry over politics, Swift has proven herself an exceptionally talented songwriter. She has remade the ABABCBB-style pop song in her image, such that other artists have begun to emulate her sharp attention to detail and her formula of writing verses around individuated experiences and choruses that most everyone can relate to. (To be clear, she did not invent this pop songwriting method; rather, she has put her own stamp on it to the extent that you can immediately tell a Swift song when you hear it, even if it’s sung by other artists.) To my ear, no other pop songwriter can craft a bridge like Swift. Over the course of six albums in 12 years, Swift has clearly demonstrated her worth on formal terms.

When one’s curiosity extends beyond the hermetic bubble of a Swift song or album, however, she and her music hit a hard limit. When alt-right websites began to trumpet her as an apotheosis of Aryan racial purity, she couldn’t muster a public statement decrying white supremacy. (She had her lawyers handle the matter quietly.) She encouraged fans to vote in 2016 but never indicated her preferred candidate. (And given the breadth of Swift’s mostly white fanbase, it’s possible that this milquetoast message resulted in a vote or more for Trump.) On her June tour stops, Swift delivered a Pride-themed speech hoping for “a world where everyone can live and love equally”, but in July, she offered no words about a world in which the US government was systematically tearing 18-month-old children away from their parents.

Most relevantly, given that she is a musician, Swift has received flack for borrowing musical elements from African American culture without speaking any words in service of racial justice. Reputation builds its sonic world around trap percussion, rapped verses (see “Ready for It” and “Endgame”), and phrases like “Bass be rattlin’ the chandeliers” that border on minstrelsy. In her review of the album, Ann Powers pointed out how Swift’s turn to black musical forms resembles a move other white female artists have made when attempting to redirect their careers in new, racier directions. For all of these reasons, listeners and critics who believe that a piece of culture must be responsive to its worldly environment have fertile ground to occupy in decrying Swift.

Given the turmoil unfolding in the real world, this signature self-referentiality becomes almost parodic on Swift’s Reputation Tour. As a journalist and fan, I’ve seen hundreds of live performances by artists across many genres, but never have I experienced a spectacle that was at once so large and so insistently insular in its focus. You walk through the metal detector at FedEx Field, you sense the aroma of chicken fingers invade your nostrils, and from that moment forward, you will be given no reason to let your thoughts wander outside the ruthlessly Swift-focused environment that you are sharing with 60,000 other humans. Because everyone is trying to Insta-Story and Snapchat their experience at once, you may not get cell service, so even if you do feel curious about the latest Trump-era fiasco during the show, you probably won’t be able to check Twitter or the news. Every last video image, musical number, and inter-song monologue concerns Swift herself or the decidedly non-political messages she projects about distinguishing what’s true (love, friendship) from what’s fake (your reputation)… which, come to think of it, still relate back to Swift anyway.

- Taylor Swift's 'Reputation' Tour Is an Unstoppable Pop Spectacle

- Taylor Swift: Reputation (review) - PopMatters

- Power Struggle in Beauty Pageants - PopMatters

- Taylor Swift - "The Man" (Singles Going Steady) - PopMatters

- Taylor Swift: Folklore | Music Review - PopMatters

- Taylor Swift's "seven" Marks the End of Innocence - PopMatters

- Taylor Swift: evermore | Music Review - PopMatters