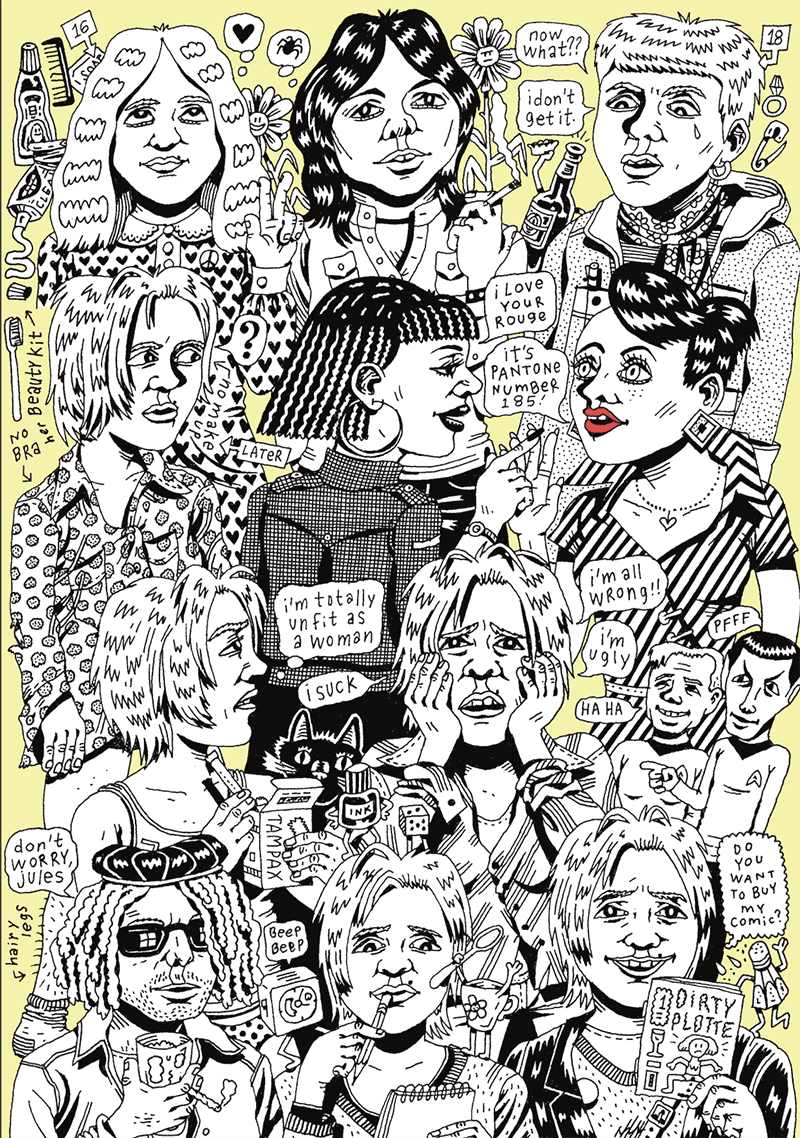

I don’t speak French and have never even visited Quebec, so my googled translation of plotte as “vagina” and “slut” likely misses some cultural connotations. Julie Doucet‘s longer and better explanation includes a map and diagram and appears in one of the first issues of her ground-breaking ’90s comic, Dirty Plotte—or rather her bandes dessinées, literally “drawn strips”, the French term and tradition Doucet responds to.

I have never read Doucet in her original format, but my bookshelf includes My Most Secret Desire (2006) and My New York Diary (2013), two reprint collections of roughly 100 pages each. But her original publisher, Drawn & Quarterly, has now released a complete collection, Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, a massive anthology spanning over 600 pages. It amasses not only all 12, 20-something-page issues of the original 1990-1998 series, including full-color front and back covers, but also roughly 200 pages of additional work produced during the same period. The combination is a startling body of work that further deepens Doucet’s place in the comics cannon.

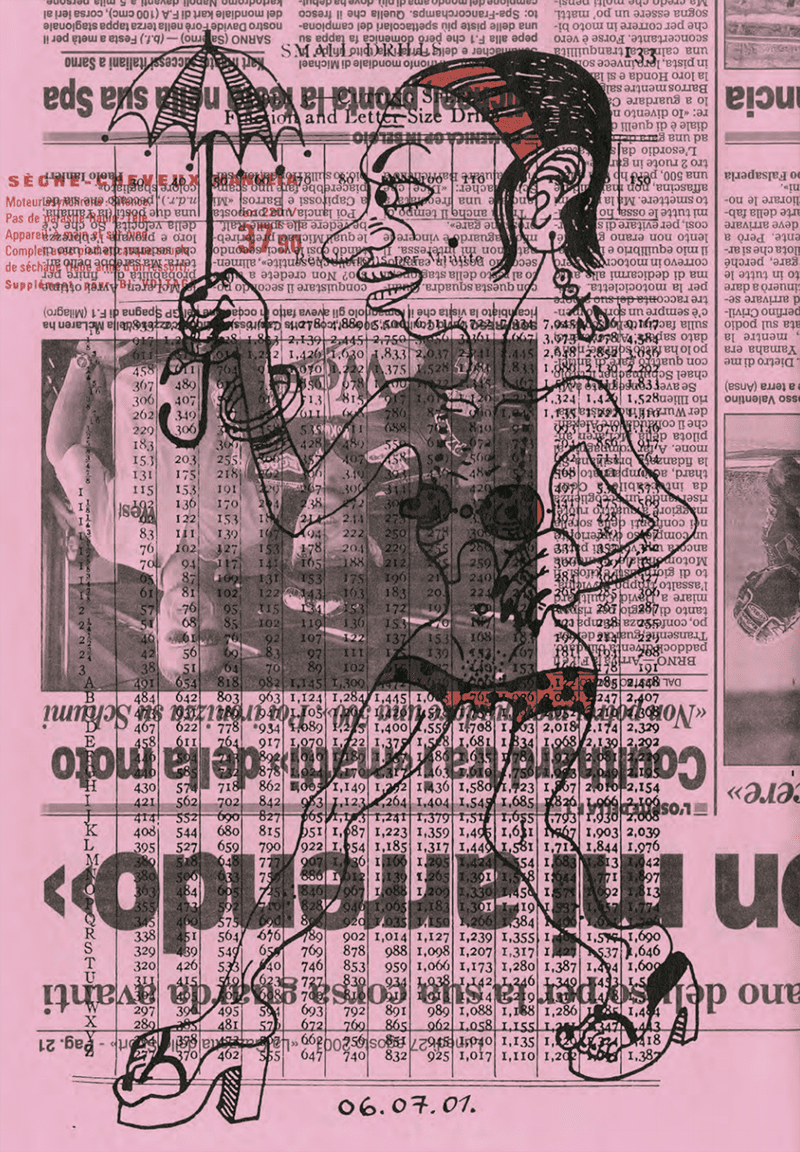

Dirty Plotte began as a late ’80s series of two-page mini-comics, which, if we believe the cover price, Doucet sold for only a quarter. Most of them appear within the pages of the expanded series, one of the first publications launched by Drawn & Quarterly—with, according to the second issue, the grant support of the Canadian government’s ministry of cultural affairs. The fact is a stark contrast to the roughly simultaneous controversy in the US over the National Endowment of the Art’s funding of Andres Serrano‘s Piss Christ (1987), with conservative Republicans attempting to eliminate the NEA entirely in 1990. I can only imagine how they would have responded to Doucet’s comic about the decapitated and butchered body of Christ on her dining room table, or the comic about a serial killer murdering a child (a young Doucet?) in a park and feeding the corpse to his trusty dog.

I know Doucet primarily as a memoirist whose diary-like subjects are the recent events of her waking life as well as the surreal happenings of her sleeping subconscious. Both paint a vivid and now expanded self-portrait. Doucet dreams she eats a butter-oozing croissant protruding from a man’s briefs; she watches her comics role model Chester Brown swim with killer sharks; she is stabbed in the eye with a drug-filled syringe; she receives the gift of a cut-off penis from a friend (it may or may not grow back); she masturbates with homemade cookies in a spaceship; she wanders lost in the underground tunnels of New York; she has sex with her mirror self; and she witnesses a prostitute strip off her clothes and then her skin to reveal a dog who strips down further to a snake.

Though many of her other stories are equally surreal, Doucet is careful to distinguish dream content, citing a “true dream” or a “story based on a long time dream” or dating both the dream and the comic separately (“Dreamt July 1995 – drawn January 1996”). The distance of even a few months makes the work memoir not diary, but the effect is still diary-like as Doucet documents the disturbed and disturbing events of her subconscious life. She also nods at early 20th century comics pioneer Winsor McCay‘s Little Nemo in Slumberland strips, each of which ends with the child protagonist waking in bed—a pose the cartoon Doucet often repeats.

Her conscious world, however, isn’t clearly divided from her dream life. Many of the dreams begin ambiguously, implying real-world events that then devolve uncomfortably. Her non-dreamt content is infused with many dream-like qualities too. After declaring, “I’m in my bed! It was only a dream…” the cartoon Doucet is surrounded by the objects of her apartment literally muttering murderous threats. Her cats can not only talk, but lead their own anthropomorphic adventures continued across multiple issues. Other stories begin realistically and then turn not to dreams but fantastical comedy—as when she visits an old friend to find that he has a dog so big that your voice will echo if you shout down its penis. Still others are dream-like wish-fulfilments, as when she murders her annoying roommate or imagines multiple installments of “If I Was a Man” (it turns out a penis can make a lovely flower vase).

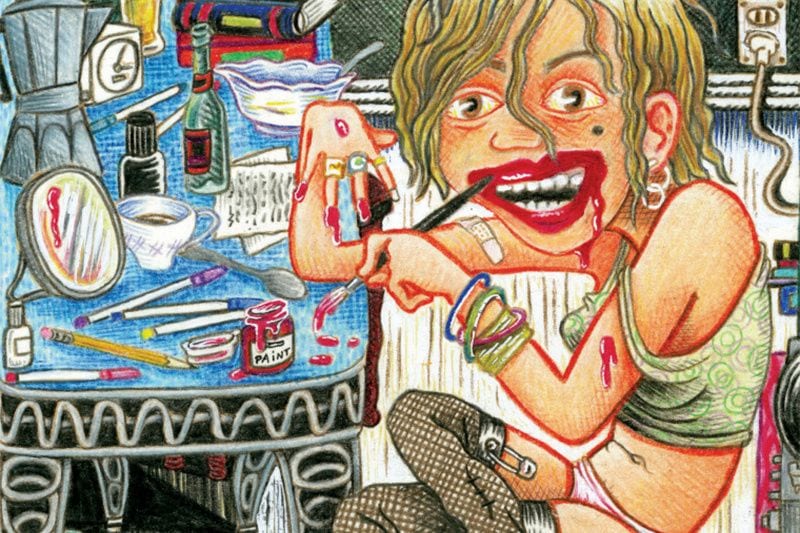

Doucet’s creative id, whether awake or asleep, knows few boundaries—or rather seeks out boundaries to challenge. I’m not sure whether I’m more uncomfortable looking at Doucet’s self-portraits covered in self-mutilating razor wounds or when she more graphically mutilates a male volunteer’s corpse. She is also “dirty” in both senses, depicting herself as a nose-picking slob living in surreal squalor and as an insatiable masturbater craving elephant trunk. Like her contemporary, Fiona Smyth, there’s a fair amount of “joyous sucking” in these pages—but Doucet’s sexual universe is overall much darker. While the dreams and waking fantasies disturb, it’s her less surreal, less sensationalistic memoirs that most upset.

The first installment of what she would later collect as “My New York Diary” begins in Dirty Plotte No. 7. The ten pages, the longest sequence yet, recounts her 17-year-old self foolishly falling in with a group of men who variously coerce her into kissing and eventually having sex. It’s not a rape scene, but the cartoon Julie’s “Oh, well” thought bubble is hardly joyous even if she does leave the apartment pleased with her sudden adulthood. As one of Doucet’s readers writes generally of the series: “Julie, it’s really not very funny, is it?”

Yet Doucet’s visual style is comical. These are cartoons in the exaggerated sense, impossible anatomy that evokes the human proportions it warps. The heads of Doucet figures are roughly 1/5th their height, so roughly double the size of human heads. They pose and move in clunky, almost Peanuts-esque shapes. The artistic choice often reduces the level of discomfort in each scene. A more naturalistically drawn 17-year-old Doucet pinned on a mattress under a gray-bearded man sounds like an image more horribly at home in a Phoebe Gloeckner collection. Doucet instead allows her reader and perhaps herself off the hook by refiguring her dreams and memories into unrealistic realities.

The collection is divided into two, oddly distinct books, each with its own title page and numbering. The first is the complete Dirty Plotte series. But rather than interspersing Doucet’s non-Plotte material between issues, the editors rewind to the late [80s and begin the timeline over with literally “Everything Else”. “Everything Else” includes almost a dozen short essays about and interviews with Doucet by an array of comics aficionados: Dan Nadel, Diane Noomin, Chris Oliveros, Adrian Tomine, Jami Attenberg, J.C. Menu, Andrew Dagilis, John Porcellino, Geneviève Castrée, Laura Park, Martine Delvaux, and Christian Gasser. All but the last were published during Doucet’s comics career, which Gasser’s interview looks back over from the vantage of 2017.

To be clear, the “Complete” in the collection’s title refers only to Dirty Plotte and similar work she produced at roughly the same time. So it does not include her 365 Days: A Diary (2008) or Carpet Sweeper Tales (2016), works that break from her ’90s style and content—though not necessarily from the comics form, despite claims that Doucet left comics entirely after 1999. It does, however, include the 41-page episodes of “The Madam Paul Affair”, her first major work after ending Dirty Plotte.

Wandering back through the ’90s again, it’s often unclear why certain material was included in Dirty Plotte and other material wasn’t. There are more dreams (pregnancy), new cat adventures (now in a Western setting), and “If I Was a Man” installments, and works like “Heavy Flow” and “Janet and the Tampons” feel like long-lost sisters. But some of the gutter shapes are more playful—several waves and squiggles stand out—and an occasional page like “The Kiss”, an apparent homage to Klimt, do seem wonderfully out-of-place here. Perhaps if Doucet had felt freer to experiment in these ways she might not have left comics at all.