In the weeks following the American presidential election last November, journalists asked a range of prominent figures in professional sports for their views on Donald Trump. Implicit in this exercise is an assumption that athletes, by dint of their celebrity and their responsibilities as role-models, have something pertinent to say about politics.

Some, like the San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich, have spoken out forcefully against what they see as a grave threat to American democracy and civil rights. The captain of the United States national soccer team Michael Bradley, declared himself “embarrassed” by Donald Trump’s “xenophobic, misogynistic and narcissistic rhetoric”. When the US and Mexico played a World-Cup qualifier several days after Trump’s election, the two teams posed together for the ritual pre-match team photo in what was widely seen as a rebuke of Trump’s plan to build a wall between the two countries. Colin Kaepernick of the San Francisco Giants, who last season knelt during the pre-game singing of the national anthem in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, represents the most forceful — and controversial — example, hailed as courageous by some, decried by others as unpatriotic, condemned even for inappropriately injecting politics into an arena imagined as apolitical. (See Colin Kaepernick and the Perils of Patriotism as Fandom by Chadwick Jenkins.)

Sport, of course, has never been a stranger to politics. Hitler organized the 1936 Berlin Olympics to celebrate Aryan racial supremacy. The football league tables of former eastern bloc countries are today filled with teams whose names — from Spartak Moscow to Energie Cottbus — are the lyrical inheritance of regimes that used sport to celebrate the proletariat. The rivalry between Real Madrid and FC Barcelona maps historic conflicts over Catalonia’s separatist aspirations. The fan violence that erupted at a Dynamo Zagreb-Red Star Belgrade match in 1990 served as one of the triggers that launched the civil war in Yugoslavia. These are all examples of states using sport to narrate their ideologies, or of communities assigning political valence to particular teams. Muhammed Ali’s refusal to be drafted and fight in Vietnam, or Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists, heads bowed, on the 200 meter sprint podium at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, are rare cases of individual athletes seizing on their sport as a platform for political expression.

As the authoritarian-populist firestorm gains strength around the globe, forcing the world of professional sport to make difficult choices, it could do worse than meditate the example of an athlete who died almost five years to the day before Trump’s election, and whose trajectory tested possibilities for political action and invested his sport with new aesthetic, social, and political meaning.

* * *

Early Sunday, 4 December 2011, Sócrates Brasilerio Sampaio de Sousa Viera de Oliveira died in a Saõ Paolo hospital of complications from an intestinal infection at the age of 57. The Brazilian midfielder ranks as one of the greatest and most beloved players in the game’s history, and the news sent the football world into mourning.

It’s part of the character of modern sports that the death of a great athlete provides occasion for hagiography. Journalists, commentators and fans alike join together to remember — and to communicate solemnly to those who were too young to have followed the dead athlete’s career — that this was someone worth remembering. Considered collectively, the litany of deceased heroes endows each sport with a history, gives it density and texture, and legitimates it, as if to say that because it has a history, this sport is more than simply a game. The very way most people speak and write about sports history — as a recitation of sports greats, of victories and losses, of records broken and athletic deeds accomplished — conveys a simple message: the athletes of the past were great, some were greater than others, those who practice the sport today are perpetuating a great tradition, and what a glorious, timeless sport this is.

Broadcasters’ hyperbole and the flood of athletes’ biographies that narrate triumph over adversity, the extraordinary character of their accomplishments, and their exemplarity for aspiring sportspeople, all aim at peopling each particular sport’s pantheon. These ingredients work together to create a modern mythology of sport, founded on the notion that athletic activities convey important life lessons and carry a larger meaning. Saturated in sentiment and heroic narrative, which conveniently erases the often brutal social, economic and political realities of professional sport, a great deal of this is insufferable, maudlin stuff.

But it would be a mistake to place Sócrates in that same Pantheon. To those who saw him play, followed his career, and admired the man, his passing represented more than the death of yet another sports hero. Sócrates may not be the experts’ choice for greatest player of all time, but he, in testing its cultural, social, and even political possibilities, defined its golden age more than anyone else. Football for him was not a mere game, animated by a utilitarian calculus of victory and defeat. Instead, it was an aesthetic practice of a high order, one that aimed to delight, inspire, and even edify. With Sócrates died not just a gifted player, but an ethical model, who preached and practiced the conviction that professional athletes bear serious social and political responsibilities, and who showed that football could in fact be something more than a sport.

Sócrates’ path to football glory was as unlikely as his career unique. Born in the town of Belem in northern Brazil, he grew up in a middle-class family of civil servants. Surrounded by books and raised by parents deeply committed to education (when naming Sócrates and his two brothers Sóstenes and Sófocles, his father turned to his personal library for inspiration), Sócrates pursued advanced university studies, ultimately earning a doctorate in medicine. Even after beginning to play for his first professional club, Botafogo in Ribeirão Preto where his family had moved when he was two, Sócrates insisted on continuing his studies and medical residency. He refused to train full-time with his club or to play for the Brazilian national team until he had completed his degree.

At six-foot-four, skinny and long-limbed, Sócrates brought an altogether unlikely physique to the pitch, although any impression of ungainliness evaporated as soon as his tall frame began to move. Elegant in his carriage, he covered space and touched the ball with grace. He was one of the most complete midfielders in history, who could protect the ball, dribble, pass, create, and score. A consummately skilled, perfectly two-footed player who was also good with his head, his technique was nothing short of astounding: he could direct distant passes and score from long range with devastating effect. He was a master of what in French is called “cleaning up the ball” — the ability, when receiving a badly-timed or misfired pass, to use one’s ball-handling skills, patience, and vision in order to allow one’s team to reorganize, before passing the ball to a teammate in a strong attacking position.

The tall Brazilian was the antithesis of the great Argentinian playmakers, Diego Maradona and his heir Lionel Messi, both pocket-sized players who conjugate their low centers of gravity, explosive speed, and exceptional dribbling skills to blow by opponents with sudden changes in direction, the ball seemingly glued to their feet. Sócrates played at a slower pace, his head up, constantly on the lookout for teammates, open space, or breakdowns in opposing teams’ defensive shape. He shook off players defending him with neither velocity nor power, but with his ability to anticipate, control the ball in unexpected ways, and move into spaces at the very instant they opened up. He was a profoundly relational, even altruistic player, who always made his teammates better.

Above all, he displayed wondrous creativity, ever ready to place his technique in the service of the beaux gestes, with hook turns, no-look passes, and seemingly impossible long-range blasts on goal. His trademark was the blind back-heeled pass. In the feet of lesser players, such low-percentage show-boating ignites irate tirades from coaches. But with Sócrates’ uncanny vision and technique, the weapon seemed to add an extra dimension to the pitch, a new axis to the wondrously variable geometry connecting him to his teammates in attacking phases of play. Pelé said that Sócrates played better backwards than most players do forwards. His only real weakness was that shared by his generation of Brazilians: rigorous defending was simply not part of the Socratic method.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Sócrates had style, too. With his unruly dark hair and beard, the Bjorn Borg-like hairband, the intense gaze, the raised clenched right fist with which he celebrated his goals recalling the Black Power salute, Sócrates represents one of the most powerful and enduring images of football in the ’80s.

Though Sócrates began his professional career with Botafogo SP, where he played between 1974 and 1978, it’s with Corinthians that he is most closely associated. The most popular club in the São Paulo megalopolis, carried by a passionately devoted supporter base and closely tied to Paulista working-class identity, the Time de Povo (the “People’s Club”) offered a perfect stage upon which Sócrates could perform. There, between 1978 and 1984, Sócrates scored a remarkable 172 goals in 297 matches, and led his club to three São Paulo state championships.

Sócrates also captained one the most distinguished Brazilian national teams in history. Between 1979 and 1986, he earned 60 caps and scored 22 goals, playing alongside an exceptionally talented generation that included fellow midfielders Zico and Falcão. They had the good fortune to play under Telê Santana, a coach whose temperament and conception of football made it possible for their creative mayonnaise to take. The pilot of the great 1982 and 1986 national teams, Santana championed what Brazilians call o jogo bonito (“the beautiful game”), a term that had pretty much ceased to hold any relation to the realities of high-level soccer by the time Nike appropriated it for its 2006 World Cup advertisement campaign. With Santana, described by one Brazilian journalist as “the last romantic technician of Brazilian football — of a beautiful football, a football of goals, oriented to the attack, football-art”, Sócrates had found his football soul mate.

Indentured Players

What did Santana’s vision of “the beautiful game” actually look like on the pitch? Rather than impose a formal system in which, say, one or more of his midfielders were restricted to defensive duties or assigned to mark specific opposing players, the coach gave his midfield players complete liberty to position themselves and mount attacks as they saw fit. Sócrates’ role was playmaker. Loosely anchored to the center of the midfield, he was charged with orchestrating attacks, setting the pace, distributing balls, and — in keeping with the freedom of movement Santana afforded his players — making runs towards the opposing goal.

This was samba football. Play was not lightning fast and attacks could be slow to unfold, but players were in constant motion, the geometry of their shifting positions unfolding in mesmerizing patterns on the pitch, put to rhythm by the unceasing beat of Brazilian supporters’ samba bands in the stands. Everyone on the side played with impressive technical skill, intelligence, and collective purpose. Their fluid attacks were the fruit of spontaneity and creativity rather than rigorous tactical organization. More than tools for mounting effective attacks, their astounding controls, dribbles, passes, and strikes were expressions of on-field creativity for its own sake, and communicated sheer fun. The players celebrated their goals with a few graceful dance steps and joy in their faces. They love what they do — and you can’t help but love them, and what they are doing, too. One can only imagine how proud Brazilians were to send such a team to the 1982 World Cup — so splendid, and so certain of winning. This was the first World Cup that I could follow with any real understanding, and it was terribly hard not to wish I was Brazilian just to be able to share fully in the ecstasy.

Brazil’s third goal in the 3-1 win that sent defending champions Argentina home from the 1982 World Cup is a perfect illustration. In one motion, Sócrates picks Maradona’s pocket deep in Brazilian territory and backheels a precisely trained pass to Falcão. With three touches Falcão carries the ball across the midfield line as the striker Eder follows him up the left side. Passing the ball to Eder, Falcão immediately makes a run forward towards the left flank. Eder one-touches it ahead to Falcao, who one-touches it back to Eder. With an Argentinian player closing in, Eder prudently cycles the ball laterally to the left back Júnior who has advanced into the midfield. Júnior finds Zico and immediately sets off forward. Zico controls the ball with one touch while following Júnior’s deep run toward the Argentine goal with his eyes. With his second touch, Zico threads a perfectly-timed diagonal pass between Argentina’s two central defenders to a Júnior in full sprint, who one-touches it past the Argentinian keeper into goal. Júnior just has time to trace a few samba steps before being swept up by his happy teammates. Trademark Brazil.

Five Brazilian players — nearly half the team — touch the ball. Each player with the ball immediately looks for an available partner to pass to. The players without the ball are in perpetual motion, seeking open space and offering solutions to their teammate with the ball. Brazil’s ever-evolving positioning leaves the Argentinian side looking slow, static, and a pass behind play. For every successful pass, there are also at least two other open teammates in excellent passing position. Everyone works together to keep play advancing forward. And, it must be said, Júnior’s foray far forward of his defensive zone betrays the team’s venal (or was it mortal?) sin to neglect defensive assignments. Everyone plays simply, with as few dribbles as possible (three out of seven passes are one-touches), privileging the short pass over long balls or lengthy runs with the ball. No one hogs the ball, no one engages in extraneous virtuosic displays. When football is played this well, it looks easy, obvious, self-evident.

The terrible truth about the great ’80s Brazil teams, of course, is that none ever won an international title. At the 1982 World Cup, Sócrates’ irresistible squad danced its way to the second round, only to be felled by a cruelly efficient Italian side that knew its defensive scales cold. Brazil’s confrontation with Italy was but the latest in a long series of clashes between two diametrically opposed styles of play, a kind of philosophical disputation in an ongoing disagreement over how football should be played.

In the ’60s, when Brazilian football had already become synonymous with beautiful play, Italian players were being schooled in the peninsula’s patented catenaccio (“lock”), a tactical system that emphasized defense, surrendering possession to the opposing team, and mounting lightning-fast counterattacks upon recovery of the ball. When Pelé’s Brazil blew out Italy’s catenaccio 4-1 in the 1970 World Cup final, Brazilian commentators viewed the win as a victory of futebol arte over futebol de resultado (“art soccer” over “outcome soccer”), of aestheticism over pragmatism, of “poetry” over “prose”. The 1982 game was a return match of sorts, pitting Santana’s jogo bonito against the catenaccio’s newest avatar. An inspired Brazil played true to form.

Sócrates scored Brazil’s first goal, controlling a Brazilian throw-in inside their own half, dribbling up field, and after a beautiful give-and-go with Zico, sliding a pinpoint shot past Italy’s best player, keeper Dino Zoff, at an impossibly tight angle. (Sócrates even scored the equalizer in extra time which would have sent Brazil through to the semifinals, but which was rightfully ruled offside). Italy played the entire game inside its defensive tortoise-shell, steely resisting attack after attack. This time, however, prose defeated poetry. Paolo Rossi, the Italian striker coming off a two-year suspension for match-fixing who scored a hat-trick to seal Italy’s 3-2 victory, entitled his autobiography Ho fatto piangere il Brasile — I made Brazil cry. But it wasn’t just Brazilians who bawled. The great English footballer Bobby Charlton, who was calling the match for BBC, had tears in his eyes at the final whistle.

Sócrates and his teammates were well aware that they were carrying the banner for a particular philosophy of football. “Is that why you have come all this way? To discover whether it is more important to win or to play beautiful football?” Sócrates asked a British interviewer. “Beauty comes first. Victory is secondary. What matters is joy.” The game, in his eyes, was just that: a game, or rather, an aesthetic exercise, whose purpose was to bring pleasure. One can only imagine the tantrums professional coaches today would throw if their players held forth in this vein.

Sócrates broke with the mores of top-flight football in other ways, as well. He didn’t use an agent. He left Brazil for Italy to play for Fiorentina in an era when few players crossed oceans to compete in foreign leagues. While in Florence, he audited university courses in political science. His taste for tactical freedom, cigarettes, and drink proved incompatible with the rigorous defensive systems and training regimens of the Serie A, and he only spent a year there (1984-85). His coach at Fiorentina called him “A loveable nuisance.” One of his teammates recalled, “it’s true he liked a beer and talking politics”. As Sócrates himself put it, “I am an anti-athlete. You have to take me as I am.”

* * *

Before his Italian interlude, however, Sócrates would, as one of the organizers of the “Corinthians Democracy” movement, play a key role in a crucial turning-point in modern Brazilian history. In 1982, Adilson Monteiro Alves, a 35-year-old sociologist, was elected president of the Corinthians club on a reform platform. Subscribing to his progressive views, Sócrates had threatened to retire from professional football if Alves was defeated in the election. With Alves’ blessing, and under the leadership of Sócrates and his teammates Walter Casagrande, Wladimir, and Zé Maria, the team launched a campaign to improve the difficult conditions in which professional players plied their trade in Brazil at the time. Players were locked into a contract system that kept them poorly paid and indentured to their clubs, which were in turn kept under the tight grip of corrupt and well-connected presidents. This was not a protest organized by spoiled millionaire athletes holding out for yet more cash. As Sócrates explained, “Ninety percent of players live in inhuman conditions. Seventy percent earn less than minimum wage.”

Corinthians’ players took charge of all team matters, agreeing to manage them collectively based on utopian socialist principles. Gate, television, and sponsoring revenues were shared with the club’s employees. All details of team life — mealtimes, training, tactical organization, choice of coaches, and player transfers — were voted on by players. At once symbolic and playful, they voted to allow beer in the locker-room. Sócrates described the movement’s goals in 1983: “I’m struggling for freedom, for respect, for ample and unrestricted discussions, for a professional democratization … and all of this as a football player, preserving the lucid and pleasurable nature of this activity.” It remains an admirable credo for workers’ rights in any workplace.

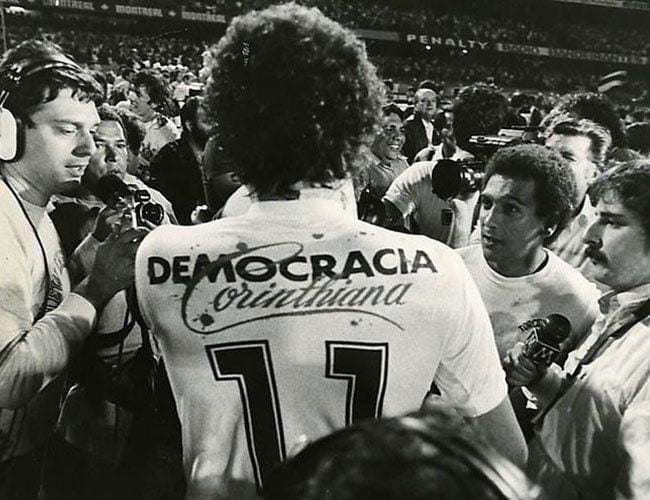

The military dictatorship’s tight control of Brazil’s national sport — in 1979-80, the Brazilian federation was run by Heleno de Barros Nunes, an admiral and high-ranking official in the ruling ARENA party — made the players’ next step a logical, if also courageous, one: to transform Corinthians Democracy into a political movement opposed to the generals. According to Sócrates, “At the start, we wanted to change our working conditions; then the politics of sports in our country; and finally, politics as such.” They mobilized their jerseys as weapons against the dictatorship. During the run-up to the 15 November 1982 elections for federal deputies and senators, state governors, and municipal councils — the first elections since the 1964 coup that brought the generals to power — the players printed “Dia 15, vote” (“On the day of the 15th, vote”) on the backs of their jerseys.

Their choice of coach was as much a political statement and an experiment in collective workplace management as it was a tactical option: teammate Zé Maria, an emblematic Corinthians player who wore their colors from 1970 to 1983 and who had played on Brazil’s 1970 World Cup champion team, had also just won office as São Paulo municipal councillor in the 1982 balloting. During the 1983 São Paulo state championship, they again lent their jerseys to the political struggle, this time printing “Democracia Corinthiana”. At the championship finals against Paulista rival São Paulo FC, the team entered the pitch carrying a banner emblazoned with “Ganhar ou perder mas sempre com democracia” (“Win or lose, but always with democracy”). They won 1-0, capturing the championship for the second straight year. The goal scorer? Sócrates, who for once found himself on the receiving-end of a back-heeled pass.

Fighting for Liberty

For Corinthians’ players, social and political justice, the workplace as cooperative, the team as community, and football as art all fit together as part of a coherent, seamless ideal. They imagined Corinthians Democracy as a laboratory for social and political liberation, one that, “by using the language of soccer” (Sócrates’ words), might help teach Brazilians democracy. Rather than distract them from their athletic duties, direct workplace democracy and political action only seemed to inspire them on the pitch, where they played a spectacular and joyous football Sócrates again: “We practiced our profession with more liberty, joy, and responsibility. We were a big family, together with the players’ wives and children. We played every match in a festive atmosphere … On the pitch, we were fighting for liberty, to change the country. The atmosphere we had created gave us more confidence with which to express our art.”

Throwing the full weight of his celebrity behind the struggle for democracy, Sócrates took an active role in the Diretas-Já (“Direct elections now”) movement and dared the regime to throw him in prison. More than 1.5 million people gathered at a Diretas-Já rally held in São Paulo on 10 April 1983 — 15 days before federal elections — which still stands as the largest political demonstration in Brazilian history. Taking the microphone, Sócrates pledged that if Congress amended the constitution to allow presidential elections, he would decline Fiorentina’s offer and stay in Brazil to help build democracy. The amendment was defeated, a discouraged Sócrates left for Fiorentina the following season, and Corinthians Democracy died a slow death. Despite attempts at Palmeiras and São Paulo FC, no other clubs succeeded in following Corinthians’ example. In 1985, the managerial clique that Alves had helped to sweep aside retook control of Corinthians, and promptly put an end to the experiment.

At once a symbolic, galvanizing moment and political model, Corinthians Democracy represents an important chapter in Brazil’s transition to democratic rule. Sócrates, Wladimir, and Casagrande all joined the Workers’ Party that had been cofounded in 1980 by a metalworker, union organizer, Corinthians fan, and future president of Brazil named Lula. The singer Gilberto Gil, who had already served time in prison, under house arrest, and in exile for his political views, dedicated a song to the movement (the beautiful Andar com fé — “Walk with Faith” ; Gil also later wrote a song about the club entitled “Corintiá”). In 1985, Brazil inaugurated its first civilian president since the 1964 putsch. Sócrates later described Corinthians Democracy as “the most perfect moment I ever lived.”

After returning from his year in Italy, Sócrates played one season with the great Rio de Janeiro club Flamengo (winning the Rio state championship in 1986), another with Santos, before returning to his first team, Botafogo where he retired from professional football in 1989.

As soon as he hung up his cleats, Sócrates set out on a second career as full as his first. He completed his medical certification and opened a sports medicine clinic in his hometown, Ribeirão Preto. He participated in theater and music projects, coauthored a book on the Corinthians Democracy experience (subtitled “Utopia in Play”), and was working on a novel when he died. He continued to be an outspoken commentator on football, politics, and social justice, writing several newspaper columns and giving frequent interviews. Brazil is a culture of nicknames, and Sócrates amassed several, some referring to his physiology, like O Magrão (“The Skinny One”), others to his technique, like Calcanhar de Ouro (“Golden Heel”). But the moniker by which he is most frequently referred to, Doutor Sócrates, refers of course to his medical training, but above all expresses the immense respect in which Brazilians hold him.

* * *

What’s left of Sócrates’ golden age today? Certainly, the sport has changed in fundamental ways: today’s game is faster, players stronger and fitter thanks to more rigorous training (and — if we are to believe the rare glimpses provided by, say, the Italian police’s investigation into Juventus of Turin in the ’90s — scientifically-managed doping programs), defenses are more rigorous, and tactical systems more sophisticated than they were a generation ago. Some argue that its greater speed and athleticism are precisely what make the modern game better. Others retort that more disciplined positioning, higher pace of play and the instant challenges to the opposing player with the ball have reduced space for creativity.

Without a doubt, the game was played at a much slower pace in Sócrates’ day. Defenders often contented themselves with jogging in front of players with the ball, leaving them time to look, think, and create. Today, players in the top ranks have only a split second to decide what to do with the ball before an opposing player closes in at full tilt for the tackle. One only needs to compare the slim morphologies of players in the ’80s with the muscular, powerfully built bodies that populate today’s top leagues to measure the chasm.

In Brazil itself, futebol resultado ultimately won the upper hand over futebol arte. Non-Brazilians wear the Brazilian national team jersey the world over precisely because players like Pelé, Garrincha, Zico, and Sócrates transformed games into moments of grace. So powerful is the enduring electricity they generated that most don’t seem to have noticed that, smarting from its failed 1982 and 1986 campaigns, Brazil subsequently cast its lot with futebol resultado in its determination to win at the international level. Those who remembered that Paolo Rossi scored Italy’s second goal in the infamous 1982 match after picking off a sloppy pass between Brazilian defenders can’t entirely blame them. Futebol arte’s last Brazilian gasp was heard at the 1994 World Cup, when Sócrates’ younger brother, the gifted offensive midfielder Raí, started Brazil’s first three matches as captain. He was subsequently benched and the captain’s armband handed off to Dunga, a rugged and technically limited defender who symbolized the definitive shift in tactical priorities.

The auriverde aura has thus survived a succession of sorry spectacles: the joyless, defensive Brazilian team that captured the 1994 World Cup, the inchoate assemblage that sleepwalked its way to the 1998 final, the overconfident divas who stumbled out of the 2006 Cup, and the defensive reprise engineered by Dunga, now as coach, that exited the 2010 competition early and met with humiliation before a home crowd in 2016. As for the 2002 victory — earned thanks to solid defending and a single striker in a state of grace (Ronaldo) — the great Dutch player, coach, and creator of the European pendant to Brazil’s beautiful game Johan Cruyff called it the triumph of “anti-football” (Cruyff was no less critical of his own country’s betrayal of the total football philosophy with a brutish squad in the 2010 World Cup).

For Zico, the 1982 loss to Italy represented a decisive turning point in this tactical history. In his words, it was nothing short of “the day football died… We played artistic football with beauty, all about goals and attacking… Italy were the opposite, completely preoccupied with stopping the other side playing.”

With all respect due a player digesting a disappointing loss, Zico was mistaken. The philosophical struggle between attack and defense, between aestheticism and realism, has been, and always will be, the game’s structuring dialectic. Art has bowed to realism in dramatic fashion any number of times: Cruyff’s magnificent Dutch squad lost to workmanlike West Germany in the 1974 World Cup finals; a French team celebrated as “the Brazilians of Europe” also lost to West Germany in the 1982 semifinal. And everyone who has admired the creative attacking football preached by coaches like Pep Guardiola, Jürgen Klopp, or Marcelo Bielsa knows, the present moment represents something of a golden age renewed, as far as play is concerned at least.

So what is it in football’s history that so many long for? In our nostalgia-saturated age, it was inevitable that the world’s game would be become increasingly preoccupied by its past. The sport has succeeded in becoming truly global in recent years, by conquering new markets in Asia and the United States, which have yet to see their football parade rained upon by nostalgia. But football’s historical heartlands in Europe and South America certainly have. The internet is full of websites keeping alive the memory of a happier, simpler time, replete with sepia-tinted photographs and grainy newsreel footage, the requisite hagiographies and tributes to big hair and shaggy mullets. A brisk business in vintage jerseys feeds a market of supporters hungry for kit from an era before shirts became covered with advertising and Nike and its competitors had unleashed ever uglier cycles of jersey designs to siphon a maximum of cash from fans’ wallets. There are any number of vendors happy to sell you t-shirts emblazoned with Sócrates’ effigy — the Marxist midfielder, commodified.

Capitalism is a relentless manufacturer of nostalgia, having transformed football into a capital-intensive, profit-driven spectacle. The capital that has flowed into the sport from American hedge funds, Chinese conglomerates, Malay magnates, and Persian Gulf oil fortunes has reshaped the conditions in which players learn and ply their trade, club owners and team coaches set their expectations, tournaments are organized, and supporters experience the game. It has remade a cultural form with a long and messy working-class history into an increasingly asepticized product. Consider at what cost Guardiola orchestrated FC Barcelona’s spectacular revival of futebol arte between 2008 and 2012. Barcelona spent over half a billion dollars a year to buy, keep, and pay its players. And while Barça had stood as the last major club to refuse selling advertising space on its jersey, it finally traded its principles for the Qatar Foundation’s 150 million euros in 2011. A team whose proud motto is més que un club (“more than a club”), had become, as Barça’s greatest hero and moral conscience Cruyff cruelly put it, un club més (“just another club”).

Sócrates and Corinthians Democracy

The quest for tactical, technical, and physiological efficiencies and marginal gains, all in the service of maximizing profits, has placed extraordinary pressures on players themselves, at once agents of competitive success, fungible commodities on the transfer market, and symbols whose image can be lent or sold to boost the sale of jerseys or endorsed products. Many are recruited into youth training systems at a young age — in many cases from Third World countries — where they live, eat, and breath the game before they even hit their teens, where they have little time to explore the world on their own, and where, subjected as they are to savage selection before reaching the pro game, they have little incentive to speak their mind. However extraordinary a player Messi is, it’s hard to imagine him ever articulating anything other than the programmed banalities the media and his employer expect of him.

This suits football’s new paymasters fine; they want players who will not only perform but behave like company men. Teams today have little patience for iconoclastic or outspoken figures. Consider the fate of one of the most technically gifted French footballers of his generation, Vikash Dhorasoo. Polished in one of France’s top football schools in Le Havre, Dhorasoo went on to play for Bordeaux, Lyon, Milan AC, and Paris-St-Germain. Thoughtful, well-read, and intellectually curious, Dhorasoo shot a self-reflective film in Super 8, called Substitute, documenting his experience riding France’s bench during the 2006 World Cup. After a successful season with Paris (he scored a spectacular goal from 25 meters out against archrival Olympique de Marseille to win the 2006 French Cup), his relations worsened with his coach, the dour, strongheaded Guy Lacombe.

In a remarkable testament to the closing of the football mind, Lacombe – who had made a habit of clashing with his players — convinced PSG to fire Dhorasoo, under contract for one more season. Retired from the game, Dhorasoo keeps himself busy; he has written occasional columns and kept a blog for Le Monde in which he offers frank, sardonic perspective on modern football; he sponsors Paris Foot Gay, an amateur club committed to fighting homophobia in one of the most notoriously heteronormative of sports; he has served the city of Paris as a youth worker; he spoke out against Nicolas Sarkozy’s right-wing government; and he co-founded Tatane, an association “In favor of an enduring and joyous soccer.” Sócrates would have approved.

If, like Zico, Sócrates saw the confrontation between art and realism in moral terms, he went much further than his teammate, drawing a connection between styles of play and the social and political conditions that make them possible and give them meaning. After the 1982 defeat against Italy, he defended Brazil’s play in precisely these terms: “At least we lost fighting for our ideals. And you can compare that to society today. We have lost touch with humanity, people are driven by results. They used to go to football to see a spectacle. Now, with very few exceptions, they go to watch a war and what matters is who wins. That is why I value the squad for this World Cup — it might just be a team with ideals.”

Zico was never harsher than when he criticized Brazil, whether for the shortage of youth coaches, corruption in the Federation, or the national team’s cautious play. He condemned the overly rigid tactical systems that had become prevalent after he retired, enemies of creativity that made the jogo bonito “impossible today. In the seventies players ran four kilometers a match. Today it’s triple that amount. There is no space and time for creativity. Football has become uglier as a result. That’s why in the future, football should be played with nine players per team.” Analyzing particular playing styles as expressions of political ideology, he called the 2010 World Cup Brazilian team “very bureaucratic, very conservative”, and observed that Dunga hailed from southern Brazil, where “they are the most reactionary Brazilians.”

* * *

We shouldn’t let nostalgia blind us to just how much about football’s golden age there was to abhor. No one misses the hooligan violence that reigned on England’s terraces in the ’70s and ’80s. The sport was always a business. Sócrates knew firsthand how players could be exploited by team owners and authoritarian regimes. No one who has seen the brutality with which Andoni “The Butcher from Bilbao” Goikoetxea broke Diego Maradona’s leg in a 1983 fixture can have any illusions that this was a gentler time. This golden age was no age of innocence.

But as football has become a polished, tightly controlled, and expensive spectacle, in which the closest to social commentary allowed by the sport’s governing bodies are trite “Say No to Racism” campaigns — the road to commercialized, amoral hell is paved with good intentions — something important has been lost. Sócrates showed that football could be something beautiful, that the game was inextricably anchored in and shaped by social, economic and political contexts, that all its actors had the ability and even the duty to think critically about the sport in context, just as they had an ethical responsibility to speak out for social and political justice, and that certain forms of play — and the means by which they were contrived — could speak to higher values. This isn’t to say Sócrates was perfect. He was all too human, as the fondness for alcohol which no doubt hastened his death reminds us: “I frequently drank a little in the morning, a little at lunchtime, and then a little until the evening… Alcohol was a companion, like cigarettes.” No media-manufactured cardboard hero, Sócrates was a gifted athlete, brave, idealistic, humane, and yes, human, too.

In this, the age of Trump (or of Putin, Erdogan, and Le Pen), Sócrates and Corinthians Democracy are an example for athletes and citizens alike, one that challenges us all to think carefully, courageously, and creatively about our political and social responsibilities in the face of injustice.

* * *

Sócrates always said that he hoped to die the day his beloved Corinthians won a Brazilian championship. Amazingly, fittingly, he got his wish. Only hours after his death, Corinthians kicked off against bitter crosstown rival Palmeiras in the season’s final game. Corinthians needed only a draw to clinch the national championship. 40,000 of the fiel, as the Corinthians “faithful” are known, packed into the team’s open-air Pacambeu stadium to pay tribute to Sócrates, and to support the club referred to simply as Timaõ (“the great team”). Supporters hadn’t had much time, but the terraces were nonetheless decked out in banners honoring Sócrates, recalling everything from his goalscoring to Corinthians Democracy. In the tribute at the start of the match, the two teams gathered in a circle in midfield, and Corinthians’ supporters and players raised their right arm and clenched their fists in Sócrates’ characteristic gesture. Supporters long chanted his name. Corinthians drew Palmerais, 0-0. Timaõ were champions for the fifth time.

Photo: Jorge Araújo (Wiki Commons)