By rights, The British Table should be a perfect book. Authored by venerable food writer Colman Andrews and photographed by Canal House luminaries Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton, The British Table is, unsurprisingly, beautifully written and gorgeously photographed. A lifelong Anglophile, Andrews brings his copious knowledge of all things British to bear on this fresh look at the United Kingdom’s food. The resulting book is one cooks will be eager test drive at the stove.

It’s at the stove that The British Table runs into serious trouble, with poor copyediting leading to flawed recipes: three of the of four I tested contained errors. For the record, my copy of The British Table is not an advance review copy. Wondering if I was experiencing a run of bad luck, I turned to Chapter 9: “Desserts and Confections”, for sweet recipes, unlike savory foods, require absolute precision. The very first recipe in the chapter, for gooseberry fool, had an error. The ingredient list calls for lemon juice. It’s never used in this dish.

While print errors are bound to occur in all books, printing mistakes in literary works are annoyances. Errors in recipes have the potential to ruin a dish. While not earth-shattering in the grand design, wasting food is never a desirable outcome. As an occasional recipe-tester for cookbook writers, I can attest to the enormous amount of testing and re-testing that goes into creating workable recipes. Given Andrews’s stature — multiple James Beard award recipient, co-founder of Saveur Magazine, author of the definitive Catalan Cuisine — we safely assume the recipes in The British Table weren’t tossed together. The many errors are doubly a disservice, both to readers and Andrews himself.

Before delving into the recipes, let’s backtrack a bit. Subtitled A New Look at the Traditional Cooking of England, Scotland, and Wales, The British Table takes a look at the hows, whys, and wheres of British food.

For decades British cuisine, especially English food, was the butt of jokes. There was “school food” a class of foodstuffs associated with what Americans call boarding school. These institutional dishes often bear archaic names: spotted dick, dead baby, Eton mess.

Then there was English nursery food. Bee Wilson, writing in First Bite, evokes the horrors of nursery food fed to children in the early 20th century. At the time, fear of illness and limited understanding of sanitation contributed to notions of an ideal child diet. A premium was placed on “digestibility”, with no interest whatsoever on edibility: food was either mushy and textureless or, in interests of exercising young jaws, rock hard.

Elizabeth David, herself a picky eater during childhood, is quoted here in Artemis Cooper’s Writing at the Kitchen Table, describing the fish sent up to her nursery she writes, “The food looked so terrifying even before it was on your plate.”

Postwar rationing dragged on until 1954, further injuring English food’s reputation. The British food scene has finally recovered, thanks to the Gastropub movement, popular television shows like Strictly Come Baking, and chefs like Heston Blumenthal, Mark Hix, Jeremy Lee and Fergus Henderson. Andrews writes, “The mystery isn’t why British food is so good today, but why it ever wasn’t.”

It’s true: with its access to seafood, farmland, viticulture, dairy, and a reputation for fine baking, Britain is now assuming a spot amongst the world’s finest food producers. Add to this the country’s onetime colonial association with India, resulting in a uniquely Anglo-Indian cuisine, all washed down by some of the world’s best beers and whiskeys.

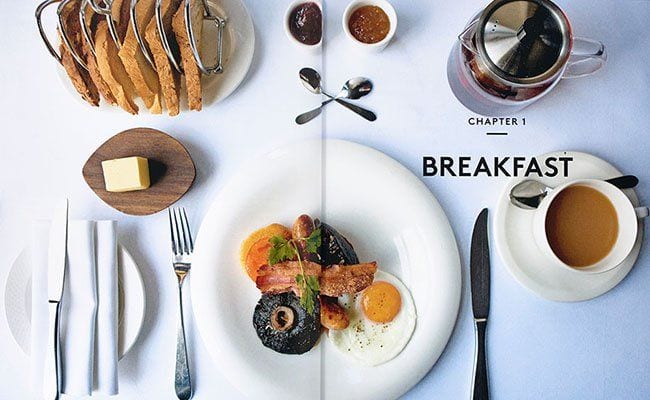

The British Table begins with breakfast, that all-important meal the Brits do so well. Hearty breakfasters can tuck into the Full English, aka “the fry-up”, a pork-laden extravaganza also known as “the cardiac special”. As Andrews explains, while the full English varies by region, order one and you’ll receive:

…fried back bacon, sausages, black pudding (i.e., blood sausage) fried button mushrooms, fried or broiled tomato halves, baked beans, and fried or poached (sometimes scrambled) eggs, with toast — white or brown — on the side and coffee or tea to drink. There may be bread fried in bacon fat or butter instead of toast, and potatoes may be included in the form of chips or hash browns (purists frown on the latter).

Lighter eaters might prefer Eggs and Soldiers, which is essentiallly soft-boiled eggs, their presentation fancied up with egg cups, toast trimmed of its pesky crusts and quartered. Or perhaps you’d fancy a spot of frumenty. Frumenty, dating to medieval times, is a sort of ancient hot wheat cereal. There are both sweet and savory versions of frumenty. Andrews gives a sweet recipe, calling for brown sugar, milk, cracked wheat, and a slug of rum. Anyone who enjoys a bowl of Cream of Wheat won’t go amiss here.

From breakfast, Andrews moves to the soup course. Those with stock IPOs might attempt Summer Lobster Soup, calling as it does for three lobsters. The poorer among us can prepare Mulligatawny Soup, the Anglo-Indian classic asking for more budget conscious lamb neck or chicken thighs, onion, apple, curry powder, and chicken stock.

Interspersed with recipes are bits of historical lore about the people, food, and places of Britain. These essays range in topic from the making Arbroath Smokies to the rise of the “Auld Alliance”. The essay about Cheese and Onion Pies is, for my money, worth the price of the book, telling readers what Linda McCartney is going on about in the song “Admiral Halsey / Uncle Albert”. Here’s the lyric:

Paul McCartney: “I had another look / then I had a cup of tea / and a Butter Pie.”

Linda McCartney, chiming in with a pseudo-uppity English accent: “A butter pie!”

Cheese and Onion Pie, or butter pies, being meatless, were eaten by Lancashire Catholics on Fridays.

The chapter on fish and seafood begins, rightly, with fish and chips, chips being the British term for fried potatoes. While nobody can argue with the wonderfulness that is Fish and Chips done right, I’m not sure this is the recipe to attempt. Likely it began well, for Julia Lee, aka The Fry Queen, a women renowned for her frying skills, is thanked in the acknowledgments. But the recipe itself is terrifying. Want to make the accompanying Mushy Peas? You’ll need to flip to page 201. Maybe it’s me, but I hate when cookbooks send you running all over the text. More alarming are the chips, or fried potatoes. You are instructed to prepare these whilst frying the fish. The recipe reads: “At the same time, prepare the chips according to the directions.”

The directions for making the chips are on page 206. You, making a batter for the fish, then deep frying said fish, are on page 67. Did I mention deep frying requires 6-8/1-.4-1.8l cups of vegetable oil, which you’ve heated to 375F/190C?

And in the midst of this, we’re supposed to flip to page 206?

Okay. For the sake of experiment — we aren’t actually cooking here — let’s go. The chip recipe is not on page 206. It’s on page 208, and asks for an additional 4-6/960 ml-1.4 l cups of hot oil. With this hot oil, you’re expected to cook the potatoes in small batches… twice.

While you’re frying fish.

Alone.

Survivors of this ordeal will be left with 10-14 cups of used cooking oil.

In happier recipe news, let us discuss the Chicken Tikka Masala. The origins of this dish remain contested — did it originate in India, or with Ali Ahmed Aslam’s Glasgow restaurant, the Shish Mahal? No matter. Make it once and understand why the British people are obsessed with Chicken Tikka Masala, or CTM. You will be, too. I have now made it twice, and have come to understand that Chicken Tikka Masala and I cannot be in the same house together because I will eat it until is gone. CTM is neither diet food nor something people with delicate digestions should make a regular habit of consuming.

The recipe’s single error does little more than confuse, a mercy. Let’s dispense with it.

The ingredient list calls for a cup of yogurt, but you’ll only need half of that, to marinade the chicken. So tuck a note in your copy of The British Table: 4 ounces/ 120ml plain yogurt.

Chicken Tikka Masala requires one cup/240 ml of Campbell’s Tomato Soup. In the United States, Campbell’s Soup is sold in 10 3/4 ounce cans, meaning one is left with 1 3/4 ounces of soup, or about 59 ml. Maybe you’re creative. Or hungry. Me, I poured the whole can into the pot, with no ill effects.

Having breezed past these minor bumps, marinate the chicken breasts in yogurt, cumin, ginger, turmeric, cayenne, and salt, brown them, then set them aside. Deglaze the pan, sauté some onion and garlic, add a little more fire in the form of chili and curry powders, the aforementioned Campbell’s, whatever yogurt marinade remains, and some heavy cream. Allow this mess, which will look like a sickly shade of under-mixed paint, to cook for about 20 minutes, remembering to make some rice. Slice the chicken into pieces and add them back to the pan, allowing everything to finish cooking.

The result will be smooth, rich, tangy, and deceptively spicy, the kind of heat that sneaks up on you after a few bites. It’s delicious. Chicken Tikka Masala is hard to stop shoveling into your face.

Welsh Salt Duck — I omitted the classic onion sauce accompaniment — is mercifully simplified from Lady Llanover’s First Principles of Good Cookery. Duck rubbed in coarse salt, left to sit for 48 hours, poached, then roasted. While dry brining is a classic method of both preserving and preparing foods (confit) there’s usually a third step in such recipes, called clearing. The salt is rinsed thoroughly in cool water, then the poultry is put back in the refrigerator for 12-24 hours, during which time all the extra salt “clears”, or works its way out of the bird, leaving it pleasantly seasoned but not over-salted. The Welsh Salt Duck recipe did not call for clearing. Instead, one rinses the salt and goes directly to the cooking.

While I found the resulting dish barely edible for saltiness, my husband did not. Nor am I ready to blame the recipe, for salts vary, as do ducks. I’d make this again, decreasing the amount of salt and inserting the clearing step. Nor would I necessarily blame the recipe — all salts are different. As are ducks.

According to Andrews, lobscouse, or scouse, possibly derives from the Latvian labs kausis, meaning “good cup or bowl”. The good cup in question is a sailor’s stew, once made from salted meat, thickened with hardtack, and “So closely associated with the port city of Liverpool that scouse is a slang name for a Liverpudlian and for the Liverpool dialect.”

The recipe Andrews gives is decidedly more modern, calling for fresh chuck steak or stewing lamb, thickened with potato rather than hardtack. Unfortunately, the recipe is — I can’t think of a polite way to say this — a mess. The ingredient list calls for 1 1/2 pounds/700g chuck steak or stewing lamb, 4 medium onions, a 500ml bottle of ale, 1 pound/450g potatoes, and 5 cups/1/2 l beef stock, store-bought or home-made. Additional ingredients include carrots, rutabaga, bay leaves, salt, pepper, and thyme.

Readers are instructed to brown the meat in the olive oil. You then add the onions and beer, which is brought to a boil and reduced by half. Add the carrots, rutabaga, half the potatoes, bay leaves, and thyme. Season generously. Cover the pot, cook for 45 minutes. Add the remaining potatoes. Cook the stew until all is tender.

Meanwhile, those five cups of beef broth sit, forgotten, on the counter. This may be a blessing in disguise, for five cups of broth to one and a half pounds of meat will give you soup, not stew. Let’s not even discuss four onions.

The recipe instructions might warn unsuspecting cooks that boiling beer foams rapidly and is best watched, lest it boil over.

Normally, when recipe testing for reviews, I obediently follow instructions. But between the near-beer boil over and forgotten beef broth, I lost faith in the scouse recipe and went off piste. Four onions became one, forgotten beef broth became one cup of unsalted chicken broth. All the potatoes were added at once. The stew was slid into a 350F/175C oven.

Happily, the results were excellent. Stewing lamb in beer — I used Higson’s Best — adds a flavorful depth that’s difficult to describe; it’s simultaneously sweet with an edge of bitterness, rounded off by the broth and yes, thickened nicely by the potato. I snuck in a turnip, which played well with its root vegetable friends. Do salt heavily.

While the recipes are for experienced cooks only, The British Table transcends its flaws with beautifully informative writing, breathtaking photography, and the author’s heartfelt love of place. Read The British Table and long, now more than ever, for Albion.