Last year marked the release of the Cure’s long-gestating 14th album, the critically acclaimed Songs of a Lost World. The record is more akin to downtempo, introspective albums like Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers than the ones in the Cure cannon that skew more upbeat, such as 1987’s Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, and the breakthrough that arrives this year at the doorstep of its 40th year, The Head on the Door.

The Head on the Door was the first Cure album to break them into broader consciousness in 1985. It’s still beloved today by critics and fans alike as a paragon of musical cohesion and as one of the records that shaped the more mystical pop soundscapes of the 1980s.

For many, The Head on the Door was the gateway drug into the Cure cosmos, that dichotomously delightful and disturbing dream dimension that ultimately defies description and yet somehow makes perfect sense. The Cure cosmos, you see – music, lyrics, videos, visuals, fashion – possesses a logic all its own, and The Head on the Door is the apotheosis of that captivatingly peculiar realm of reason.

Indeed, you could say that The Head on the Door is the first proper surrealist pop album. Not only do the Tim Pope-helmed videos showcase the Cure’s quirky visual mien – members sporting manic, gravity-defying manes and disheveled clothing that suggests toddler tantrums – but the songs capture the subconscious paradoxes that often only make sense in hallucinatory moods.

That’s precisely what surrealism, as both a historical movement and modern style, aims toward: generating alternate states of consciousness that invoke incongruous imagery, startling the senses and subverting reality as we know it. In other words, lucid hallucinations. These hallucinations can be sleep-induced or curated in purely wakeful states that are subtly attuned to a grittier reality beneath the surface. Or, they can be drug-inspired.

The Cure are well-known for their youthful drug habits, after all, but the ingestion of hallucinogens by the band allegedly reached its zenith on The Head on the Door predecessor, The Top. The Top is a masterwork of psychedelic mindfuckery. However, where The Top takes us on a dark and delirious Alice in Wonderland misadventure, The Head on the Door draws us out of that rabbit hole into one that leads to a lighter place merely tinged with noir.

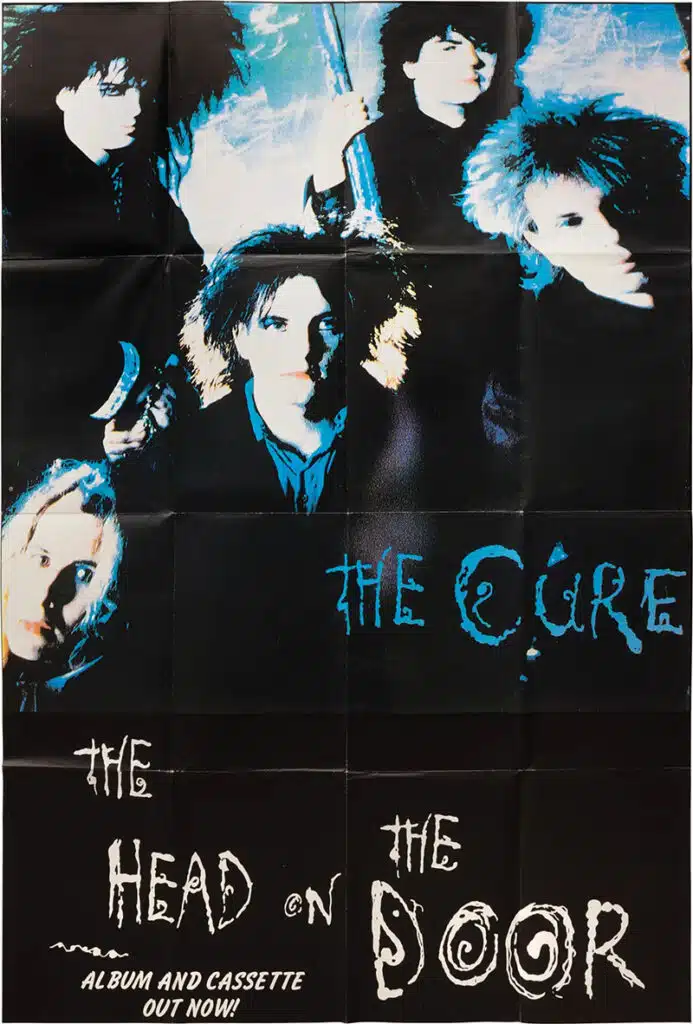

Where The Top was a magic mushroom tea musical, The Head on the Door is a neon nightmare, emphasizing the neon glow-in-the-dark pop songs that gather the gloom and turn it inside out. We’ll start with the cover – the titular visual whose ghastly glow and blurry, bleary image has some kinship with the fantastical works of Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, and Toyen and hints at the (dis)contents within. This image (actually a manipulated photograph of vocalist Robert Smith’s sister) is meant to conjure a vision Smith saw in a dream (“He saw his own detached head stuck to his bedroom door.”).

Then we have the cartoonishly creepy, swirling lettering. Both the visual and the lettering were rendered by the Parched Art collective composed of artist Andy Vella and Cure guitarist Porl Thompson, who would go on to design other notable Cure album covers as well. For a gal like me on the cusp of her 20s as I was in 1985, consumed mainly with the classic rock and shiny pop of the times, the trippy The Head on the Door cover alone was enough to inspire me to purchase the tape at my local record store utopia, Sundance Records in San Marcos, Texas.

I had not heard one peep of the songs within. The Cure were on the cusp of becoming MTV darlings, but it hadn’t quite happened yet, so I was blind to the idiosyncratic charms of the group until the very moment I happened upon the cassette. My poetic self was starting to come to sharper fruition, and I was intrigued by the otherworldly cover and title of The Head on the Door.

Growing up, my professor parents had taken us to Europe, where we visited many ruins and museums, germinating a lifelong visual art obsession. So, I was attuned to visual art in all media, and in the case of The Head on the Door, I very blatantly judged a tape by its cover. I figured the music within must match the intriguingly unorthodox cover.

When I popped the tape into my home cassette player, let’s just say my “head” exploded. The opening song and lead single, “Inbetween Days”, unfurled, yielding a jangle-pop/synthpop hybrid that vocally and lyrically captures that most invigorating of contradictions: an ebullient wistfulness. The singing begins joltingly: “Yesterday I got so old I felt like I could die.” Right away, we know we are not in for a happy ride, nor will we be transported straight into hell; rather, we are guided toward a purgatory of extreme moods and sensibilities.

Where 1982’s beautifully bleak Pornography took the Cure to the edge of the proverbial abyss and subsequent early titles like “The Lovecats” hinted at the dizzy, fizzy pop that would later leap off of theKiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me album, The Head on the Door reveled in the compelling contrasts that lurked within the sounds and lyrics. The sunny synths and high-energy guitar strumming in “InBetween Days” collide against a more mournful bassline, and lyrics and vocals are colored with melancholy.

Can we talk about the texture of Robert Smith’s voice for a minute? Like a molten mirror come to life, his voice is the most recognizable aspect of the band’s signature sound. In many ways, his voice exists as its own instrument, capable of invoking giddy highs and dreadful lows while sounding liquified, gleaming, haunting.

“Inbetween Days,” with its emphasis on “trios”, as per Robert Smith (“days, people, places”), is also augmented by an iconic video directed by none other than iconic videographer Tim “Pap” Pope, who has produced dozens of the band’s videos and a few of their concert films as well, including “The Cure: Anniversary 1978-2018 Live in Hyde Park”. The Cure and “Pap”, suffice it to say, have a legendarily synergistic relationship.

Once I viewed the “Inbetween Days” video, there was no turning back from this surrealistic pop group’s gravitational pull on my soul. My life almost instantly metamorphosed into something more whimsical and cerebral.

The bright/dark dynamic of “Inbetween Days” leads seamlessly into the next track, a tune infused with Far Eastern shadows, “Kyoto Song”. According to Robert Smith, it was inspired by a fever dream and the fear that his lifelong love, Mary Poole, would drown. This song was my foray into mystical music that could saturate the senses.

The discovery of The Head on the Door dovetailed with my entry into college, where I would soon be exposed to the symbolist literature of Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire. At my small, rural, yet wholly reputable liberal arts college, I would also be introduced to art like Joan Miro’s. So my social life (dancing at goth clubs, going to punk parties, sporting freaky fashions) and academic life strangely converged. Surrealism was making its mark in both my school and social realms.

“Kyoto Song”, with its lightly ominous oriental aura, gives way to the overtly flamenco-flavored “The Blood”, which emerged after Robert Smith imbibed a cheap Portuguese wine called Lachryma Christi. The fierce flamenco guitars, castanets, and a danceable beat fortifying Smith’s intonation of “I am paralyzed / By the blood of Christ” invoke an atmosphere of religious dread.

After the one-two global music gut-punch of “Kyoto Song” and “The Blood”, we slide into the off-kilter cubist pop of “Six Different Ways”, whose darkly playful piano tones pilfer directly from “Swimming Horses”, a song crafted during Smith’s time in Siouxsie and the Banshees. On the surface, “Six Different Ways” is a love song, but it is also about, as Smith hints, “multiple personalities”.

The eternally electrifying “Push” wraps up side one and features the most savory of Cure signatures: the epic instrumental intro. Smith claims a trip home inspired it, but it takes a darker turn into paranoia about a love triangle scenario. Like many early Cure lyrics, these lyrics harbor cryptic meanings and are often predicated on clashing ideas, ideals, and inspirations. Surrealist poetry is never straightforward; its appeal and influence lie in its secret symbols and ulterior logic. Over time, “Push” has become a fan favorite at Cure shows, as its exhilarating intro and chorused shouting of “GO! GO! GO!” and “NO! NO! NO!” literally pushes the crowd into a frenzy.

I distinctly remember that when I first heard side two’s opener, “Baby Screams,” I thought I had entered another dimension. In retrospect, it’s not even the most bizarre of Cure songs (for me, that would be “A Man Inside My Mouth” from Join the Dots and also the EP Quadpus), but at the time, I had only experienced Pink Floydian psychedelia. “Baby Screams”, on the other hand, is soaringly psychedelic in a way that deranges the senses, a principle that Rimbaud advocated in his poetic worldview.

The track’s wailed pleas of “heaven, give me a sign” amid “useless” waiting for “nothing at all” seem to be an almost suicidal supplication to the universe. The high-pitched howl emanating from Smith is perfectly matched by guitars that swirl and swell; the entire song gives a feeling of transcendent ascension even as the lyrics seem mired in hopelessness.

While The Head on the Door has been noted for its fluidity, that doesn’t mean it has an omnipresent mood. The songs flow effortlessly into each other, indicating a cohesive sound palette, but they possess their own persona; they are not monochromatic replicas of each other by any stretch.

“Close to Me”, the second and most successful single from The Head on the Door and possibly the centerpiece of the album, is a lighthearted lament about “impending doom”, whose cozy claustrophobia is embodied in Tim Pope’s iconic “wardrobe video”. The song features handclaps, a chirpy keyboard, heavy breathing, and vocals of almost childlike angst. The anxious lyrics and vocals entangle with the capricious music in a way that jitters the nerves; there is even a lyrical nod to the record title (“If only I was sure that the head on the door was a dream”), cementing its status as the piece de resistance of the album.

“A Night Like This” is the subsequent song and the third and final single whose “words were written in the rain”, according to Smith. It features a dark and stormy night mood, with imagery evoked of lovers parting into a midnight void and a desperate search ensues. Romantic anxiety is a common Cure theme, and this song, in particular, showcases the most straightforward, least surrealist song on The Head on the Door. Musically, it has muscle, too, and is clearly inspired by more traditional rock formulas, mostly eschewing dreamlike qualities for a slightly more orthodox approach. There’s even a saxophone solo.

That brings us to the last two songs that bring us back into the surrealist-pop fold with “Screw” and “Sinking”, two diametrically opposed songs tone-wise, with “Screw” standing out for its jarringly abrasive textures and drug-induced lyrics, and “Sinking” mimicking a drowning mode, with deeply meditative piano and bass and a slow-motion progression, wrapped around lyrics about getting older and becoming less authentic.

The Head on the Door is the sound and the look of the Cure coming into their own. They would continue to evolve because they don’t know how to stay still; The Cure are restless and relentless shape-shifters. But with The Head on the Door, they reached a wider audience, cultivating a more accessible pop sensibility while infusing surrealistic seasonings to satisfy their hardcore base. Robert Smith said with The Head on the Door that he intended to make pop music in the style of “Strawberry Fields”, and he succeeded. The Cure, after all, have often been tagged the “The Alternative Beatles.”

By 1986, The Head on the Door had sold 250,000 copies, far exceeding the 50,000 or so average of previous records. Melody Maker named it their Album of the Year, and “Inbetween Days” was the first single of the Cure that appeared on the US Pop Charts, peaking at number 99. Just four years after The Head on the Door, the Cure would be playing to 50,000 people upon the release of Disintegration, their best-selling record.

However, The Head on the Door was the album that started it all: It inaugurated the Cure’s ascent into arena stratospheres. With the help of Tim Pope, the Cure would finally become the MTV darlings they were destined to be, flaunting their darkly whimsical musical persona like a surrealist painting come to life.