I’ve always been more interested in reading books than collecting them, and I don’t have much patience with hardcore bibliophiles who care less about what’s in a volume (i.e., words) than what’s on it in the way of nicks, marks, coffee stains, and jacket rips. This is why I don’t share the general admiration for the 2002 documentary Stone Reader, wherein filmmaker Mark Moskowitz sets out to find the reclusive author of an out-of-print novel he read 30 years earlier; it’s a potentially great subject, but apart from the novel that touches off his quest, Moskowitz seems to regard books as so many baseball cards — agreeable objects, maybe even cherished ones, but fungible all the same.

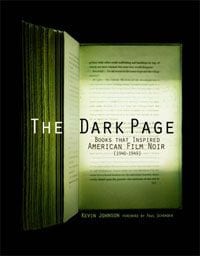

This said, I had an enjoyable time reading The Dark Page: Books That Inspired American Film Noir [1940-1949] by Kevin Johnson, a dealer in rare tomes and the proprietor of Royal Books in Baltimore, the city I call home. Clearly a labor of love, the very big volume offers a scrupulous listing of the novels, plays, and other literary sources that inspired great noir productions of the 1940s. Every left-hand page holds information about such a book and the movie based on it, and every facing page displays a large photograph of the pertinent volume, always in a first edition. Each book commentary includes a brief discussion of its content and a summary of the “points” to look for — color of binding, placement of blurbs, numbers on copyright page, and so on — when determining whether it’s a first edition; the material on each film includes a listing of the major credits, a quick précis of the plot, and often a quote or anecdote that captures the tone and texture of the production. Three appendices fill in some gaps. No slave to consistency, Johnson follows his interests and instincts wherever they lead, giving the volume a pleasantly meandering mood despite the rigor of its format. This is bibliophilia with heart.

It’s also cinephilia with brains. Johnson begins the introduction by correcting three misconceptions about film noir that are all too common among professional movie critics, not to mention casual moviegoers. Noir is not a genre but a cycle, Johnson accurately notes, carrying a set of stylistic traits into actual genres as diverse as melodrama, western, and horror. Although crooks and cops are common in noir, he continues, the cycle’s plotlines and character types are enormously varied. Nor is noir an inclusive term for any and all dark-toned pictures — it refers only to movies of the ’40s and ’50s that trace their lineage to German expressionism of the ’20s, hard-boiled fiction of the ’20s and ’30s, and the unease felt by Americans during the war-torn ’40s and commie-fearing ’50s. Noir-like movies made before 1940 are antecedents of the cycle; those made after the mid-’60s are neo-noir spinoffs. While exceptions can be found to all of the above, a grasp of these parameters can enrich moviegoers’ appreciation of true noirs and near-noirs alike.

Johnson put amazing energy into tracking down the first editions pictured in his book, and I wish he recounted more of his adventures in the text. Some came from booksellers, others from libraries like the fabled Bodleian at Oxford, and others from who knows where. As he approached his final deadline with one elusive volume still unfound, an online database pointed the way to a copy in a New Zealand library, which obligingly scanned the cover and e-mailed it to him. You can see it in on page 334: The Mills of God by Ernst Lothar, filmed by Universal as An Act of Murder, starring Fredric March and Edmond O’Brien, in 1948. If a storybook ending like this can happen, I’m almost tempted to join the collecting game myself.

So much conscientious work went into The Dark Page that it’s no fun reporting a few flaws. For a book about books, it has a surprising number of typos. The title may confuse people a bit, since it’s also the title of a 1944 novel by Samuel Fuller, himself the writer-director of some towering noirs. Nearly all of the commentary material is drawn from other books and essays, and while many of these were written by such admirable experts as William Luhr and Chris Fujiwara, it’s too bad Johnson hasn’t taken this opportunity to extend noir historiography beyond its existing boundaries. Newcomers to bibliophilia may have to look up terms like “topstain” and “presentation edition” and “Haycraft Queen Cornerstone,” which a small glossary could have illuminated. Although the photos are often marvelous, Johnson’s goal of displaying “perfect” copies led to an unspecified amount of digital manipulation, combining of elements from multiple sources, and the like, which — to my eye, at least — lends a slightly unreal quality to some shots; and giving each one a full page precludes supplementary close-ups of details scouted for by first-edition hunters.

Don’t get me wrong, though. The photos are the backbone of the book, and they’re stunningly diversified, influenced by everything from “graphic design trends, deco, dada, [and] futurism” to the no-nonsense demands of the book-buying public, as filmmaker Paul Schrader notes in his foreword to the volume. And there’s more to come: Johnson is compiling two follow-up tomes, one about American noirs released between 1950 and 1965, the other covering British and European noirs. So pack your rod, put on your trenchcoat, and lower the lights. The Dark Page has a bright future.