“Fuck the corporate media,” [Matt] Drudge told [Steve Bannon on election night]. “They’ve been wrong on everything. They’ll be wrong on this.”

“Trump,” Bannon proclaimed, “is the leader of a populist uprising … Elites have taken all the upside for themselves and pushed the downside to the working- and middle-class Americans … Trump saw this. The American people saw this. And they have risen up to smash it.”

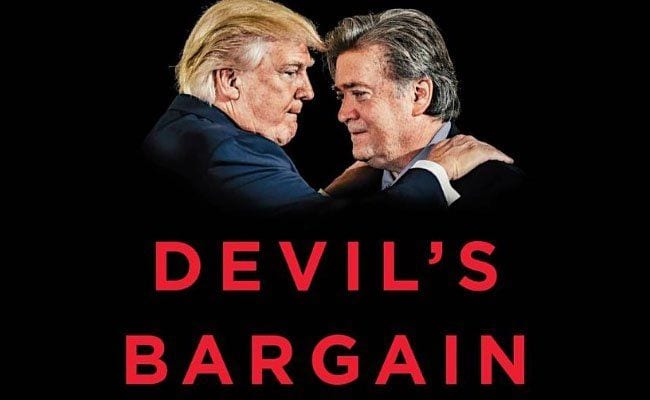

— The Devil’s Bargain

Years from now — assuming that books are still being published and we aren’t just wandering dazedly through a burnt-out cultural void of screaming memes — the books written about the 2016 US Presidential election will fill even more shelves than those written about Watergate. They will discuss the strategies, the major players, and the trendlines that led to this decision or that. Some books will also analyze how, in 2016, a fury-fueled flim-flam man broke almost every rule about presidential campaigns and became the most powerful man in the world. Those authors will argue with good reason that 2016 was the election that changed everything. For those looking back from that uncertain future, Joshua Green’s superb chronicle of Steve Bannon’s role in Donald Trump’s rise to the White House, The Devil’s Bargain, should be one of the first texts they consult.

A veteran political reporter who skips the horse-race mentality common to the DC circuit, Green is the right man for this book. His deeply researched October 2015 Bloomberg Businessweek feature, “This Man is the Most Dangerous Political Operative in America“, stands as the ur-text for most people’s awareness of who Bannon is and why they should care. That early connection to Bannon provided Green with the kind of access that the flocks of reporters who came after him were unlikely to receive, and helps give this book the sturdy spine that keeps it from degenerating into fear and hyperbole.

Those reactions, combined with confusion and panic, are precisely what Bannon would want. The character who emerges from Green’s portrait is an all-American type, the swaggering and foul-mouthed operative convinced he has discovered the secret recipe for victory. But he’s also a relatively new species on the political scene: the visionary media maven and agitator who uses billionaires to buy pitchforks for the angry masses whom he can then direct at any target he chooses.

In other times, Bannon would be a strange revolutionary. But this is an era of retrenchment and reaction that Bannon slots into just as neatly as less talented functionaries like Tom DeLay, Karl Rove, and Jack Abramoff were able to during the anti-Clinton groundswell of the ’90s. The thunderous revolt that Bannon led would be far more successful, and shocking.

Bannon was born into a middle-class Irish-Catholic Democratic Virginia family that emphasized tradition and hierarchy more than most (his parents, opposed to the modernist reforms of Vatican II, later turned to Tridentine Catholicism). His early resume would resonate with many other white men raised in the ’50s and ’60s who went into the military and then business, turning conservative in reaction to what they saw as a degenerative slide into permissive liberal chaos.

Bannon passed much of his 20s in the Navy, his time in the Persian Gulf coinciding with Carter’s failed rescue of the hostages in Tehran. This low tide in American prestige disenchanted him with the state of American institutions, inculcated a fear of radical Islamism, and set him up to be enraptured by the coming of the great modern American conservative showman, Ronald Reagan.

After leaving the Navy, Bannon spent the ’80s at Harvard Business School and later working 100-hour weeks at Goldman Sachs, then still a quality investment firm focused on growing businesses. Arriving at the start of the junk-bond era, Bannon imbibed some of the spirit of risk-taking pirates like Michael Milken. This informed the Hollywood stage of his career, where he spent a few years making a mint advising on studio acquisitions (the period when he almost inadvertently acquired a piece of Seinfeld). From there, Bannon’s ambition and eye for the next big thing led him to Hong Kong, where he made money in a way almost inconceivable at the time: using low-paid Chinese labor to harvest virtual currencies for trading in the massively popular online gaming universe World of Warcraft.

By this point in Devil’s Bargain, Green has painted a coherent, if inexplicable, portrait of Bannon. The dueling sides of his personality would seem to be incompatible. On the one hand was the faithful son who attended a private Catholic military academy, served in the armed forces, worked at a white-shoe Wall Street firm, was well-versed in the classics and history, and held no truck with the liberal proclivities of many of his fellow baby boomers. He might have been a Hollywood guy, but he was the kind of Hollywood guy who produced reverential documentaries about Ronald Reagan and groused about liberal groupthink.

But at the same time, Bannon hardly seemed to mesh with the kind of establishment Republicans gathering at the Koch Brothers’ conferences. He was the happily profane and sloppily attired bomb-thrower — Green calls him a “Falstaff in flip-flops” — who could make his friend and co-conspirator Andrew Breitbart seem positively restrained in comparison. Bannon thought of himself as a gleeful Visigoth storming the gates of a degraded Rome. In his mind, he was a revolutionary who had studied Marxist tactics and planned to use them in assaulting the liberal ivory towers that he believed had replaced the grand structures of his beloved Western civilization. To do so, Bannon pulled on all aspects of his work experience and private study to build a leftist elite-destroying infrastructure that needed only the lucky accident of a Donald Trump to carry it to victory.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Funded in large part by the reclusive billionaire Robert Mercer, in the years after 9/11 Bannon assembled an arsenal of weaponry to demolish the Democrats, major media organizations (which he and his allies believed to be hopelessly infiltrated by liberals), non-extremist Republicans, and their ultimate shibboleth: Hillary Clinton. Mining his knowledge of online hordes garnered from World of Warcraft, Bannon used the trolling memes of Breitbart News to stoke online anger, which Green memorably characterizes as “a rolling tumbleweed of wounded male id and aggression.” At the same time, the Florida-based Government Accountability Institute churned out reams of research, and a bestselling book (Peter Schweizer’s Clinton Cash), alleging the corruption of the Clintons and their foundation. “The collective power of the Bannon-Mercer machine,” Green writes, “wasn’t obvious to many people.”

By smearing the Clintons and feeding the backlash against modernism and multiculturalism, Bannon’s strategy set the stage for Trump. By the time Bannon took over Trump’s campaign in August 2016, the candidate was eager to throw out more of the red meat that the “lock her up” crowds at his rallies were demanding. The Clinton campaign had already been outmaneuvered, not understanding that the standards in place for previous campaigns — avoid disparaging minorities and immigrants, don’t get caught bragging about sexual assault — were about to get tossed out the window.

By playing to the nationalist fears favored by Bannon’s messaging machine, Trump believed he was gaining ground, not losing the middle. With Bannon’s encouragement, Trump blew past every red line that the punditocracy assumed were campaign-killers. All of it was grist for Bannon’s mill, according to Green: “It fed his grandiose sense of purpose to imagine that he was amassing an army of ragged, pitchfork-wielding outsiders to storm the barricades.”

What isn’t clear, either to Green or possibly even Bannon himself, is how the self-styled insurgent general imagines he will rebuild the institutions after they have been torn down. It’s possible that that was never the point. Pirates don’t build, after all. What’s also unclear at this stage of the Trump presidency is how the Bannon machine will be able to notch victories without a Hillary Clinton to kick around anymore. The danger, of course, comes when they start looking for other foes to vanquish. A rage machine needs constant fuel.

Devil’s Bargain is not a full-spectrum analysis of the 2016 election. Nor should it be. Green’s aim is to analyze the role of Trump’s Svengali in his victory and the nearly unique confluence of circumstances that allowed both men to harness the nation’s ugliest instincts for their purposes. Written in the clear prose of an experienced magazine reporter who hasn’t forgotten how to turn a sharp phrase, the book avoids the dutiful grind that characterizes too many modern political tick-tocks, like Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes’s recent take on the Clinton collapse, Shattered, or Mark Halperin and John Heilemann’s Game Change series. Fast-paced, crisp, and cogent, this is a first look into a dark corner of history whose ramifications are only beginning to be understood.