If you have the slightest familiarity with country music history, you know about the Grand Ole Opry. You’ve heard the childhood reminiscences from your favorite singers about how they’d get in from working the fields, squeeze into the parlor with the rest of their kin, fire up the family Philco, and soak in the magical hoots and hollers emanating from the Opry in Nashville, aka “Music City USA”. As for a show called the National Barn Dance, you’ve probably never heard a blessed thing about it.

Don’t feel bad — you’re far from alone in your ignorance. It is kind of strange, though, how the Chicago-based radio program, which spanned five decades (1924-1968), launched the careers of entertainers like Gene Autry and Andy Williams, and cultivated an extraordinarily loyal and widespread following, could have become so historically obscure.

Cultural amnesia, in fact, is an ever-present issue in The Hayloft Gang: The Story of the National Barn Dance. Put together by Chad Berry, professor of Appalachian Studies at Berea College, and published by the University of Illinois as part of its Music in American Life series, the collection of essays makes as much of an effort to raise questions about the program’s disappearance from public memory as it does to rectify the problem. Taking its title from “the old hayloft” which announcers identified weekly as the NBD’s home base (actually the Eighth Street Theater), the volume features examinations of the show’s peculiar legacy from a variety of worthwhile angles.

Paul L. Tyler, in a piece particularly loaded with great info, suggests that the program has, over time, been relegated to footnote status due to a consensus among country music historians that it “lacked a certain degree of country or hillbilly authenticity”. This is unfortunate, he writes, because the music — even if it lacked the African-American blues elements and steel guitars otherwise so common in country — was never anything other than rural.

A likely explanation for the show’s poor country credibility, says Tyler, is the fact that it’s been judged according to the abridged, hour-long segments that the NBC network aired nationally. Odds are that a good portion of the more ragged and rustic offerings, which listeners of Chicago’s WLS could hear during the full course of the program’s four-and-a-half hours, never made the national cut.

Equally harmful to the show’s legacy, suggest Berry and Don Cusic (at different points), are the slick and polished cowboy entertainers that the show featured regularly. It’s a little known fact that Gene Autry, the most successful singing cowboy-turned-movie star of all, launched his storied career from the NBD. So did Patsy Montana, whose 1935 recording of “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart” — remembered with far more musical reverence than those singing cowboys — sold millions of copies.

But if the cowboy image had a glaring faux-country veneer even back then (“I am very annoyed when someone calls me a cowboy,” Berry quotes Roy Acuff as having said), it was nevertheless something the program gladly projected and endorsed. The “quintessentially American and wholesome” cowboy image, says Cusic, appealed to both rural audiences as well as Chicago’s urban listeners, who were otherwise locking into a more “northern” sensibility and a subsequent disconnect from southern culture.

This leads to another big reason for the show’s historical invisibility — it aired from Chicago. Lisa Krissoff Boehm tackles this one, making a clear case for the Windy City as a “forgotten country music mecca” during the Barn Dance’s heyday. Long before the program ever came along, Chicago had established itself as a crucial east-west hub for freight trains and travelers of all stripes. The rural-oriented packing and reaping industries thrived, while thousands of Southern migrants poured into the city, bringing along their homespun traditions and tastes along with them.

Chicago was indeed the jewel of the American prairie, and radio station WLS, with its powerful wattage, could carry the National Barn Dance to many a far-flung community. But with Nashville’s ascendancy, as well as an ever-solidifying popular conception of Chicago as an urban metropolis rivaling New York City, Chicago’s country aura barely glimmered by mid-century.

The key explanation for the National Barn Dance’s demise perhaps falls in line with the contribution of radio historian Susan Smulyan, who points out (naturally) that it needs to be understood primarily as what it was — a radio show. Its early success and, presumably, eventual disappearance paralleled developments in the radio industry. The program at once addressed “forgotten and ignored audiences” while taking its message to national, mainstream audiences, she writes.

Because radio became an essential survival tool for 20th-century farmers that piped in big city info and entertainment from afar, the combination of advanced technology and cozy, “old time music” made for a formidable whole. And although Smulyan wraps things up before getting around to possible reasons why the NBD failed and why virtually no one remembers it, we might safely conclude that the steadily fragmenting and ephemeral nature of radio markets had something major to do with it.

A few other issues get scholarly attention in The Hayloft Gang. Michael T. Bertrand looks at the program’s racialized aspects, characterizing it as a “denunciation of urban jazz culture,” or a “rejection of the values associated with African Americans if not the African Americans themselves.” Kristine M. McCusker explores the implications, in an era of economic instability, of the program’s strict portrayal of gender roles (man as patriarchal breadwinner, woman as “sacrificing mother”). Wayne Daniel discusses the show’s efforts to broaden its appeal after World War II, and Michael Ann Williams attends to the interconnected histories of the National Barn Dance and the National Folk Festival.

It’s filmmaker Stephen Parry who provides the afterword, giving him an opportunity to recount some of his experiences and challenges in finishing up his forthcoming documentary. The Hayloft Gang, it turns out, is intended to be a companion volume to the film, both of which were his idea. So if you feel any disappointment over the academic hair-splitting you’ll get with the book in spite of a subtitle that promises a more straightforward narrative, hang on for the film and enjoy the essay collection for what it is.

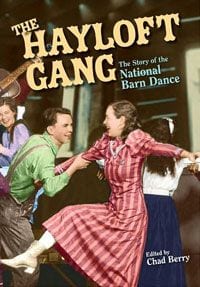

Like the colorized photo of Barn Dance regulars Scotty and Lulu Belle on the book’s cover, Parry and Berry’s Hayloft Gang projects will no doubt transform your own conception of the show and, let’s hope, repaint the faded public memory into something far more vivid.