When I was in my late teens, I found myself at a rather peculiar point in the trajectory of my existence. I was still living at home. My parents had divorced. My mother was working hard. I was working but not nearly as hard. I had a car but not a lot of friends. And I had younger siblings for whom I was partly responsible. I was old enough to stay up late but at least in my mother’s household, I was not thought old enough to stay out very late. On a Friday or Saturday night, however, I considered it my right, nay, my obligation, to stay awake into the wee hours, doing something. That insistence, of course, left me little recourse but to scan the television for its rather meager offerings.

Usually I was forced to sit through reruns of a show I probably wouldn’t have bothered with during normal hours, but occasionally I would come across a certain type of movie, a movie that, again, I wouldn’t have bothered with during normal hours. Such movies were too ridiculously lame, too poorly acted, too laughably staged to hold my attention when there were other options. But in the middle of the night, when the house was relatively quiet, they seemed to contain just the proper mixture of spookiness and kitsch to keep me firmly planted on the couch, which is the only place I wanted to be at the moment anyway.

These were the midnight horror movies or as 20th Century Fox would have it, in their series of recently released DVDs showcasing double-feature presentations of some of these films: “midnite” movies. The joy of such films was that they nearly always struck one as being wholly anonymous. No one, it seemed, could have actually toiled to produce such silliness. Rather, they seemed to have come about of their own volition, as though, somewhere in the world of experience, there was a peculiar void that could only be filled by such ghoulish camp.

The movies often starred some actors I recognized from television shows or from bit parts in other films, but even fairly established actors seemed to lose track of their training when confronted with such shoddy scripts. And yet there were a few undeniable gems along the way, movies that I might never want to discuss (oh, the shame of it) but that would come to mind on occasion, either to induce a giggle or to bring back to memory a particularly striking, if incongruous, image.

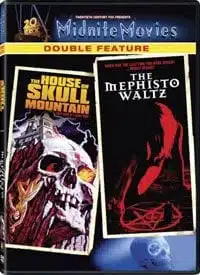

20th Century Fox’s release of a double feature DVD set that includes The House on Skull Mountain and The Mephisto Waltz brought those late nights of yesteryear back to me momentarily. The package includes only the minimum of extras (the theatrical trailers and some stills from the production) but the movies themselves are the perfect representatives of their genre. Both films boast improbable plots involving recognizable faces, hokey camera tricks taking in preposterous sets, and a commitment to the outlandish fatuity of the proceedings that is as awe-inspiring as it is absurd. And yet both films present certain moments that burrow their way into one’s memory and, perhaps, one’s affections.

The House on Skull Mountain is clearly the less effective of the two movies. It opens with a wizened woman named Mrs. Christophe, seemingly a revered voodoo priestess, on her deathbed. She sends letters to four of her great-grandchildren, none of who were aware of her or each other. They arrive just as the old woman is being put into the ground. She leaves them a cryptic note, declaring that while she has defeated her enemies theirs were merely lying dormant. Almost immediately, of course, the new tenants of the house begin dropping dead.

The film is a rather lukewarm example of blaxploitation, the credits refer to it as a “Chocolate Chip and Pinto Production”. The worst failing of the movie is the representation of the young black male of the quartet, performed by Mike Evans (recognizable as the son on The Jeffersons and the co-creator of Good Times). If his television work can be thought of as relatively progressive, his acting here is a pathetic reversion to the basest of stereotypes. His obnoxious shucking and jiving combined with his insistence upon feigned hip lingo makes his character far more suitable to the minstrel stage. When he meets one of his cousins, an older black woman, for the first time, he asks her if she “digs the spread”, then modifies it to “the pad”. When she continues to stare at him befuddled, he has to scratch his head to come up with the translation, “uhh, house”. This is poor writing, poorly delivered.

However, the film is brimming with the peculiar details that guarantee its status as a solid “midnite” movie (if not necessarily a staple of the genre). The last of the relatives to appear is one Dr. Cunningham, performed by Victor French, Michael Landon’s longtime television collaborator. Of course, the fact that he is the only white relation is as surprising to Cunningham (who apparently was orphaned, making this the first clue he has ever had to his family background) as it is to everyone else. The film thus launches Cunningham on a journey of discovery but it never allows us to arrive at the disclosure of his exact ties to the Christophe family.

This is one of several threads that the film picks up only to drop unceremoniously. There is the mysterious hatred the butler seems to have for the Christophes, a hatred that purportedly goes back several generations. By his own admission, the butler was trained in voodoo by the recently deceased Mrs. Christophe and presumably (being a powerful voodoo priestess and all) she must have known about his rage. The film never reveals the story, Cunningham merely promises to get to the bottom of it . . . later.

But this is not necessarily a negative criticism of the film. Indeed, it is part of the charm of the “midnite” movie that it promises far more than it could ever hope to deliver, that it is replete with allusions to recondite complexities that are never examined, and that it intimates depth while remaining firmly focused on the surface. These films are far more an embarrassment of riches (well, riches of a mildly titillating sort, at least) than they are a simple embarrassment. A case in point is the wonderful moment in which the younger female relation sits in her nightgown before a mirror. The combination of her reflection and the desk gives rise to the illusion of a skull, like some 17th-century painting of a vanitas. (It is rather a shame that the director decided to force one’s recognition of the allusion to a familiar trope by actually superimposing the image of a skull on the mise-en-scène.) It is a striking image that almost redeems the film from its moments of bad taste.

Such oddly inspired moments sit uneasily next to the film’s strange stabs at provocation. The House on Skull Mountain even manages, in an extended musical montage, no less, to hint at a subplot involving incestuous miscegenation. It promises a budding romance between Cunningham and his pretty distant cousin but then lets it go without comment.

The theme of incest plays a much more thoroughgoing role in the other half of this double feature, The Mephisto Waltz. This story involves the aged but brilliant pianist Duncan Ely (Curt Jurgens) who is dying of leukemia. He invites a young music journalist Miles (Alan Alda from M*A*S*H) to his home, ostensibly for an interview. The interview is immediately derailed by the pianist’s fascination with Miles’s hands. As Miles becomes ever more deeply involved with Duncan and his beautiful daughter Roxanne (Barbara Parkins), Miles’s wife Paula (Jacqueline Bisset) becomes increasingly suspicious, particularly after she witnesses a rather lubricious kiss between father and daughter at a New Year’s party.

Duncan plays the piano like a man possessed. Not surprisingly, his signature piece is Franz Liszt’s “Mephisto Waltz”, a virtuosic tour-de-force that depicts the diabolic Mephistopheles from Goethe’s Faust. Mephistopheles is Satan’s henchman who offers Faust unlimited power and pleasure in exchange for his soul. Duncan, it becomes clear, has made a similar pact with the devil and, with the assistance of the beguiling Roxanne, he contrives (at the very moment of his death) to switch bodies with Miles.

Paula soon recognizes a distinct change in her husband. He is simultaneously a more distant partner and a more passionate lover. Miles begins to practice piano obsessively and improves with remarkable speed. Paula begins to wonder how Duncan’s playing managed to get into Miles’ hands. It is the death of their daughter, however, that pushes Paula to investigate further the mysterious changes that have come over Miles, and this, of course, leads her into mortal danger.

This film has everything a midnite movie ought to have: dream sequences replete with odd camera angles and Vaseline smudges on the lens, a healthy dose of Satanic ritual and incantation (intoned in French for some reason rather than the typical Latin), bizarre murders and body exchanges managed with a small dab of blue oil on the forehead, and, of course, plenty of illicit sexual encounters (in a film where a stranger inhabits the body of the husband, even marital sex is illicit) with just enough exposed flesh to create a heady mixture of arousal and disgust. Moreover, the film’s ending boasts one of the strangest employments of the old adage “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” that I have ever encountered.

With Halloween right around the corner, now is the perfect time to indulge one’s taste for the ghoulish, ghastly, and grisly. Indeed Halloween itself, during which society momentarily sanctions exchanging identities and indulging in irrationally inane fantasy, supplies the perfect opportunity for getting back in touch with the less discerning, more susceptible side of one’s personality. These are not great films as the midnite movie genre is wonderfully immune to greatness. They are, however, a source of enjoyment that is all the more delightful for being a guilty pleasure. If you have a penchant for camp that verges on the macabre, if you prefer your kitsch tinged with spookiness, then the “midnite movie” series will be your cup of arsenic-laced tea.