The Guardian recently documented a June trek of 25 people through the city of London, on (TS Eliot’s The Waste Land 2012 – a multimedia walk, (Henry Eliot, 30 July 2012). That a poem written in the early 20th Century remains resonant with people who live nearly a century later offers a testament to its often misunderstood and always daunting language, allusion and structure.

But being citizens of the 21st Century, we need not rely solely on the manuscript and printed commentary to bring the poem to us. With new devices like Apple’s iPad, the very idea of the book as a book has been reconsidered. The Waste Land, a cooperative work between Touch Press, Faber and Faber, BBC Arena and other collaborators, releases the text of the poem through the lens of the iPad. From its earliest incarnations, The Waste Land was as much a initiator of non-fiction as it was a poem. As Eliot sought to pad out his poem for book publication, he included a series of notes, which have become famous in their own right. The scholarship and commentary on the poem continues with the Touch Press treatment, which migrates much of its new insights from print to video.

The Waste Land app first reveals a navigation screen that offers seven content choices and a Tips screen. First is the full text of poem as published in the book from in 1922 (The poem had previously appeared in Eliot’s own journal, The Criterion, and in The Dial, without notes). The app also offers the facsimile manuscript of the poem, previously published as book.

Unfortunately, the editors of the app, trying it appears to stay aligned with the published text, omit the first manuscript page with Eliot’s excision, leading to an incomplete context for the work and its history. They also fail to share any of the scholarship from the book, just images with short captions. The introduction and the editorial notes from the published version of the manuscript do not appear in the app. This is a first incompleteness. I will come to others later.

The Waste Land, like any good poem, is meant to be heard, not read. This is where multimedia offerings succeed beyond the standalone text, the random MP3 file or an LP gathering dust in a garage. Touch Stone includes five different readings of The Waste Land, two by Eliot himself. Others include Alec Guiness (Star Wars‘ original Obi Wan Kenobi,) Ted Hughes (British Poet Lauret and husband to poet Sylvia Plath,) Viggo Mortensen (Aragorn in Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of the The Lord of the Rings) and Fiona Shaw (Harry Potter’s Aunt in the film adaptations of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series).

Shaw also offers a performance interpretation of the poem, complete with music and sound effects. Shaw’s performance is available as a short, standalone film, and as an audio reading that, like the other readings, follows the text as the performers read it.

The performances are all good, and hearing Eliot with his mid-Western-affected-proper-English continues to haunt and delight. Although the other readings offer more thoughtful emoting on behalf of the audience, Eliot’s rendition provides the poet’s internal rhythm and pauses, inflections and glottal stops.

Eliot’s own notes, as mentioned, fueled enormous amounts of scholarship. Much of that scholarship was curated and condensed into line-by-line annotations derived taken from B.C. Southam’s excellent A Student’s Guide to the Selected Poems of T.S. Eliot. Southam’s book serves as the source for the app’s annotations. Click a line and the annotations display. These notes are fine for the casual reader, but because parts of Southam’s book, like sources (on page 31-42 of the sixth edition) aren’t included, the notes ultimately prove incomplete. To do the annotations justice, Touch Press needs to include Southam’s introduction and appendix.

As my three bookshelves dedicated to Eliot attest, I will acquire interesting material related to Eliot, and this app counts as interesting material, especially given the lack of DVD or download access to the original BBC documentary from which its interviews were drawn (though most of the BBC Arena documentary can be found on YouTube). The commentaries are joyfully affirmative and personally insightful.

Former punk rocker Frank Turner draws connections to Bob Dylan and contemporary pop culture. Paul Keegan provides erudite comments on Eliot and his relationship to the poem. Jim McCue a history of publication. Craig Raine dishes haughty interpretations and observations. Fiona Shaw marvels and connects with personal anecdotes. Jeanette Winterson offers right-professorial insight. And Seamus Heaney discusses what The Waste Land means to him as a poet. Unfortunately, the entire collection of commentary fits much more with documentary film-making than with serious literary scholarship.

I return to incompleteness here. Many important voices on Eliot don’t appear in the app beyond scattered references to particular lines in the annotations. Most notably, these missing scholars include Hugh Kenner, Frank Kermode, F.O. Matthiessen, Lyndall Gordon, Helen Gardner, George Williamson and Russell Kirk. They may not be available as video (or audio), but their text remains important. The majority of these critics and scholars might have presented Touch Stone with licensing issues, but given the partnership with Faber, Helen Gardner’s excellent tome, The Art of T.S. Eliot, would have been a good addition to the app’s content.

Much of the early scholarship about Eliot and The Waste Land has not yet arrived in e-reader format, though much of it is available on scholarly websites. Selections of essays or chapters would go a long way to making the app a more useful resource. Even better, given the publication and financial resources associated with Touch Press, would be a site that linked to the app, providing additional reference material on-demand.

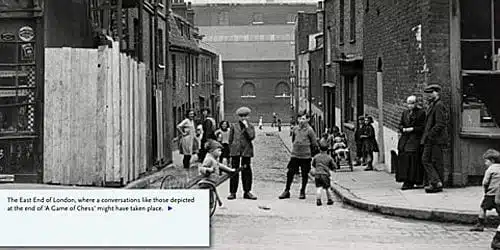

The app offers some additional data in the form of a very small set of poorly integrated snapshots meant to illustrate the poem, its author, his collaborators and the publishing process. Given the visual and location-based references in the poem, more images could surely be found that could lend value to the reading. The app would benefit from the publishers going beyond the slideshow by fully integrating the images with the line readings and annotations.

I always felt that The Waste Land prepared me for success in the Internet age. The poem that Eliot wrote and Ezra Pound helped craft fills the consciousness with fragmented jumbles of allusion and synthesis, of memory and creation, of studied eloquence and discerning observation. Blogs and other web-based content sources with their wildly far-flung links echo The Waste Land in reality, if not intent.

On the surface, the poem seemingly weaves together incongruities, but on deeper study it reveals a multi-layered structure. That hodgepodge of sources force the reader to engage beyond the surface, much as the Internet forces one from the page being scanned, to underlying sources or additional commentary. Before Vanevar Bush suggested a hypertext-like idea, Eliot apparently thought in hypertext-like form, recording his internal musings, broad reading, personal experience and intellectual associations into an exculpated whole.

For readers coming to The Waste Land for the first time, an app on an iPad with video commentary and clickable links that illuminate its language and allusions provides an appropriate entry point. For people who have studied the poem over the years, the app offers convenient access and a few new, easily consumed perspectives. I can also argue for The Waste Land app as a compelling and relatively inexpensive tool for teaching the poem, but one far from complete in its library of criticism and interpretation, and shameful in its lack of references.

The app is perhaps best for those who want to re-read The Waste Land and reconnect with a writer and an age now far removed from contemporary experience. As a work of art, The Waste Land continues to reveal truths 90 years after its first publication, in a new era of raging uncertainty and despair tempered by emergent potential.