Silent film fans are largely an indiscriminate lot. I often hear Americans say “I love foreign movies,” but of course, they never mean they love all of them. Lovers of animation or documentaries look for the cream, not every cut-rate cash-in. Even fans of certain genres, like horror or westerns or action films or musicals, rarely believe every last example is worth tracking down. Some they’ll watch only to roll their eyes at what a waste of time it is as they waste their time.

And yet, we fans of silent cinema, this special art form unto itself, this graceful glimpse of a bygone era, this revelation of lost worlds, this testament to evanescence, we basically want to see every blessed example that comes our way and we tend to treasure them all. The good news is that a lot comes our way, for these are great times of Blu-ray artifacts to go with all the restorations and archival work and silent film festivals now dotting the world.

In fact, we’re so nutty on the subject that we even look forward to return trips to the well as films previously released on DVD get a Blu-ray upgrade. Here are four such examples of these glorious revisitations, all the works of artists of genuine genius, to warm our jaded hearts and soothe our weary souls.

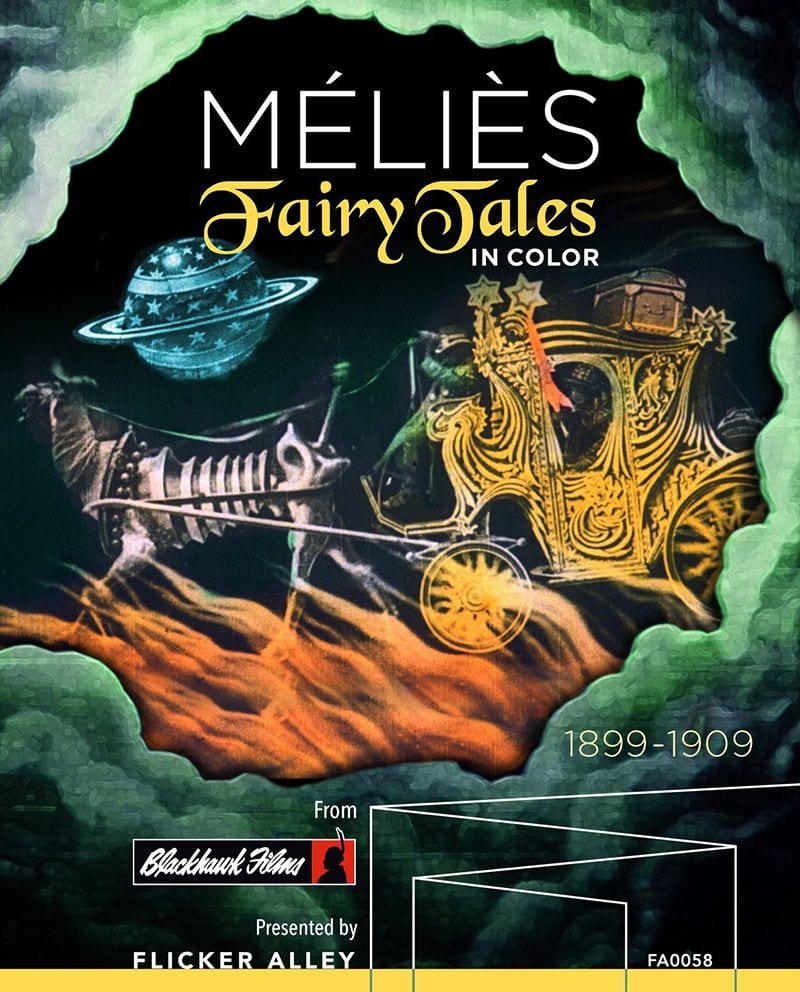

Parisian stage magician and illusionist Georges Méliès, understanding cinema as another form of magic, began creating films for his stage shows and soon went into the business of selling copies of his films. In so doing, he became the cinema’s most famous and innovative specialist in trick effects. His technical and narrative imagination seems to have been boundless, and he quickly produced epics running one or two reels in the earliest years of the 20th Century.

His most famous film, A Trip to the Moon (1902), borrows from Jules Verne and H.G. Wells to create cinema’s first science fiction epic. As this collection proves, he made other films more ambitious and spectacular.

Although he sometimes creates a panning effect, Méliès (who usually appears in his films, often in multiple roles) used a straight-on proscenium presentation, as if the viewers are sitting in the middle of the front row. He used editing for tricks and to string scenes together; close-ups aren’t here. Slapstick, burlesque and stage effects are standard; no matter how frantic or desperate the action may become, a serious tone is rarely affected. It’s all play, aimed squarely at our sense of childlike wonder and delight. One exception in this set is his 11-minute Joan of Arc (1900), which adopts religious and patriotic fervor, or at least refers to them.

Perhaps most importantly, his world is marked by continuous flux. Sets, characters and stories can only depend on the promise of transformation. This world includes plenty of cross-dressing and, in the case of Robinson Crusoe (1902), cross-racing. To witness these films is to experience a constant and unique melding of the primitive and sophisticated. If characters and worldview are simplistic, visual concepts and superimpositions are elaborate and dazzling. Then, too, sometimes a simple effect is dazzling, such as when underwater scenes are shot through aquariums so that fish and crustaceans swim in the foreground of fantastical adventures.

As the booklet explains, most of the 13 films in this DVD/Blu-ray combo were in Flicker Alley’s 2008 DVD box Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema 1896-1913. In the ensuing decade, restoration techniques have evolved to the point that, along with a few rediscovered prints, new 4K scans and digital restorations of the stenciled color techniques have made it possible to spiff up these fanciful selections. Many are presented with the option of hearing restoration producer Serge Bromberg offer narration in his heavy French accent.

In a career of over 500 movies, Méliès made other types of films, but his fairy tales and fantastic voyages remain his most characteristic and beloved creations, so this selection of the hand-colored items makes a welcome introduction to audiences who might be overwhelmed by the previous box. None of these films have been upgraded to Blu-ray before with the exception of Flicker Alley’s 2012 release of a color-restored A Trip to the Moon, reissued in 2018.

That film’s here, along with such masterpieces as The Kingdom of Fairies (1903), a splendiferous elaboration of Sleeping Beauty with underwater segments; The Impossible Voyage (1904), almost a remake or reboot of A Trip to the Moon with space and underwater scenes; the Rip Van Winkle variant of Rip’s Dream (1905); the Faustian slapstick of The Merry Frolics of Satan (1906), which casually consigns everyone to Hell; and the simple yet captivating single-stage magician antics of The Diabolic Tenant (1906) and Whimsical Illusions (1909). Méliès was openly on the side of devils and witches, as can be seen in his self-casting.

While the booklet lists the films in chronological order, that’s not their order on disc. Each film must be accessed individually; there’s no Play All option. Despite these minor inconveniences, the set is a smorgasbord of cinema in its earliest dream-state of surrealism and magic.

Another extraordinary magician of cinema was Lotte Reiniger, creator of silhouette animations that she called shadow plays. Her most famous and magnificent achievement is The Adventures of Prince Achmed, completed in 1926 and released the next year. Various sources have claimed it as the world’s first animated feature, and it’s certainly the earliest surviving one. (Recent research has uncovered an Argentine filmmaker named Quirino Cristiani who seems to have made two earlier lost films.)

Seeming to make itself up as it goes along, the story is a farrago of incidents about Baghdad, China, an African magician, the fictional land of the Wak-Wak, beautiful maidens, a handsome hero, and a lengthy flashback about Aladdin and his lamp. In short, this is a fabricated world of unabashed “Oriental” mythologies with nary a Westerner present. What matters is the delicacy and beauty of Reiniger’s vision, which she accomplished with black cut-out characters layered on top of a backlit glass worktable with multiple planes to incorporate background details in various depths. A special appearance by the genie of the lamp uses sand animation.

The scenes are tinted and the whole thing presented with a newly recorded incarnation of Wolfgang Zeller’s original score from back in the day. The film simply casts a spell, which is appropriate, since many spells are cast in the story. It’s surprising how expressive, at times even erotic, are these slips of baroquely designed paper being shuffled about. While this 1999 restoration has been on disc before, this newly scanned Blu-ray seems to bring out more of the previously faded background detail, rendering the affair even more luscious.

Reiniger had a long career in Germany and then, after fleeing the Nazi regime, in England. Working with husband Carl Koch, she made many films, most of them in fairy tale mode, and a dozen are provided as extras. The oldest, dating from 1921, uses a striking white-on-black silhouette style and turns out to be a soap commercial. Four films from the 1920s are Dr. Dolittle stories that include some non-PC African cannibals, and one of these films is included in both its English refashioning and its original German variant. Some of the 1950s films show Reiniger recycling material from Achmed.

The two beautiful color films, both Bible stories, are The Star of Bethlehem (1956) and The Lost Son (1974). The former is credited to director Vivian Milroy, with Reiniger as designer and co-animator and a score by Peter Gellhorn and the Glyndebourne Festival Chorus. The story can’t help interpolating fanciful details about the Wise Men’s voyages. The latter title retells the story of the Prodigal Son. “There he wasted his money in reckless living,” says the narrator as we witness veiled dancing girls hopping on tables; honestly, it doesn’t look that wasted.

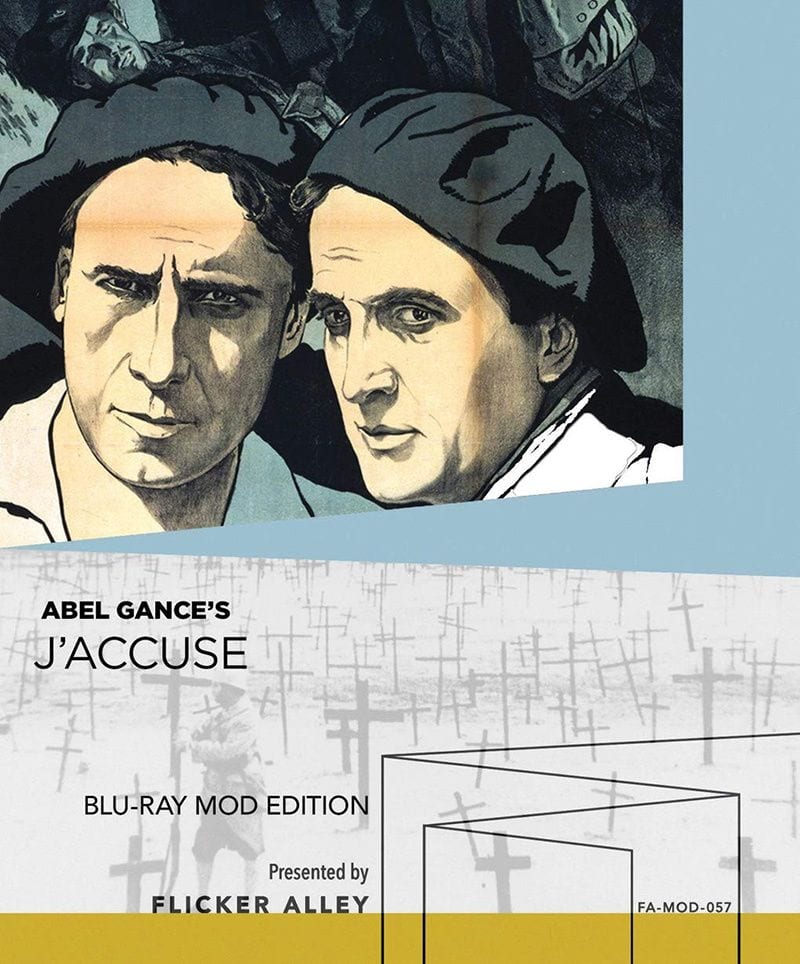

In 1919, one year after the Great War had killed millions of Europeans in the most wholesale carnage in living memory, Abel Gance released this three-hour epic of anger at war’s waste. Taking its title from Emile Zola’s 1898 letter about the Dreyfus Affair, Gance adopts the same imperious pose of the angry French intellectual and points a finger at all who participate in war, all who promote its propaganda, all who profit from it — in short, all of society.

As is common in films, the war is reduced to a romantic triangle. Sensitive poet Jean Diaz (Romuald Joubé) loves next-door neighbor Edith (Maryse Dauvray), who’s married to drunken brute Francois (Séverin-Mars). When the two men, by coincidence, find themselves in the trenches together, they eventually become buddies. Meanwhile, Edith has been kidnapped and raped by German soldiers, so that she returns after four years with a child.

Although it boasts very heart-tugging moments, the melodrama isn’t as important as Gance’s energetic and manifold command of technique, which includes poetic framing, superimpositions, moments of ultra-rapid editing (which he’d push to a dizzying limit in his next epic, 1923’s The Wheel), and scenes of self-consciously naked symbolism and theatricality. Not unlike Oliver Stone, Gance was a fluid filmmaker who used any device he could think of in the moment to catch the viewer’s attention. He shot real footage of the September 1918 battle of Saint-Mihiel, in which the U.S. Army participated, and he incorporates some of this material into a climactic battle along with thanks to those involved.

The film is most famous for the mystical, supernatural final act, in which the shell-shocked Jean, now apparently mad, informs the cowering inhabitants of his village that their dead are rising and advancing to judge whether their sacrifice has been in vain. Unintentionally anticipating every zombie movie, the film has us witness the materialization of the walking dead, garbed in uniforms and bandages, advancing remorselessly across the countryside, across the image of a military parade at the Arc de Triomphe, and finally peering into the windows of their conscience-stricken families. As powerful as this section is, Gance’s 1938 “remake” manages to be more forceful as a pacifist message in the context of an imminent war.

While the film has had many editions and variations, this tinted 2K restoration from Lobster Films and EYE Film Institute, with a score by Robert Israel, is the most complete and comes with a bonus short of French comedians performing sketches, Paris During the War (1915). Originally released on DVD in 2008, this is the film’s Blu-ray upgrade, as manufactured on demand from Flicker Alley.

This trailer without subtitles doesn’t directly represent Flicker Alley’s presentation.

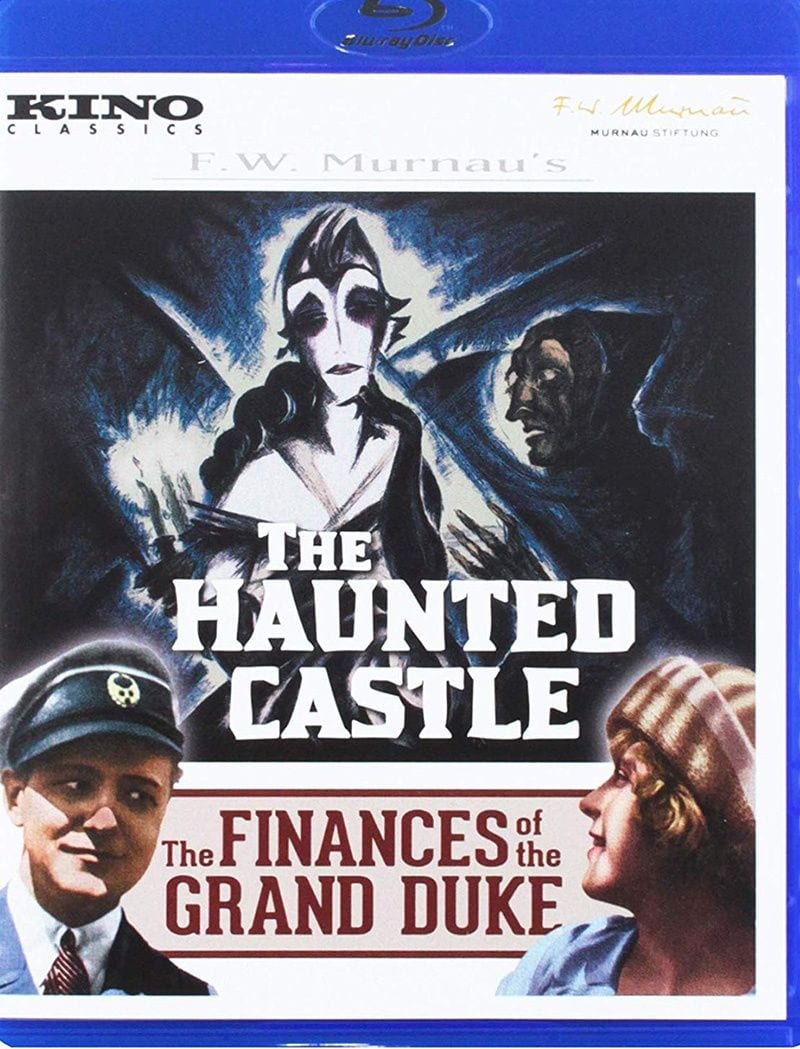

Germany’s F.W. Murnau is responsible for some of the greatest achievements in silent cinema, and neither film of this double-feature qualifies. That’s not a serious problem. Both melodramas are in such pleasing shape and show off such attractive qualities of design, photography and storytelling verve that we can appreciate them as minor entertainments clearly made on impressive budgets.

The Haunted Castle (1921) sounds like another horror tale, like Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), but you’ll be disappointed if you go looking for that. Carl Mayer‘s script follows a socially awkward weekend at a lavishly appointed mansion where the guests include a rude and glowering Count (Lothar Mehnert) who’s rumored to have killed his brother and gotten away with it.

His widowed sister-in-law (Olga Tschechowa) is among the guests along with her new husband, and so is a Roman priest who wanders around in a beard and robe like Rasputin. The truth about the brother’s murder gets revealed amid flashbacks and much mysterious theatrics of glances and accusations. Oh yes, there’s also a horrific dream of a clutching claw, followed by a whimsical dream from the kitchen boy.

More business with dreams and grotesques plays out in the serial-like plot of The Finances of the Grand Duke (1924), adapted by Thea von Harbou (Mrs. Fritz Lang) from Swedish crime writer Frank Heller’s novels about a gentleman thief. Swanky mansions were packed to the rafters with gentlemen thieves at this era, according to the literature and the movies made from them, and this example keeps throwing new characters in our face along with the anti-hero (Alfred Abel) and the hectically pursued heroine (Mady Christians). Among the cabal of quirky conspirators is Max Schreck, most famous as the title role in Nosferatu. In accordance with the era’s German thrillers, the story never makes much sense but keeps hopping too quickly for us to notice.

David Kalat’s excellent commentary provides much history for this production and the careers of those involved, and he explains that what we have today is only about half the length of the original; this may go some way to explaining the choppiness. In both cases, we have great-looking tinted prints from a 2013 Kino Lorber DVD, now upgraded to Blu-ray.

This clip without music or English titles doesn’t directly represent Kino’s product.