In their finest moments (say, Fonda in Twelve Angry Men and Stewart in Vertigo) we see how the extremes that test our humanity are not outsized erruptions of mythic force but simply part and parcel of everyday life.

Two of the most iconic male screen actors of their generation, James Stewart and Henry Fonda were also the best of friends. Both untrained actors (Fonda studied journalism at the University of Minnesota while Stewart attended Princeton to pursue architecture) and both more interested at first in working on the stage than in film, Stewart and Fonda provided some of the most unforgettable performances ever to leave their indelible marks upon celluloid.

Fonda began pursuing acting on the recommendation of Dorothy Brando (the mother of Marlon) and joined the Omaha Community Players, much to the chagrin of his idolized father — the latter soon came around after seeing the young Henry in his first starring role. Stewart produced his own childhood plays at his home in Indiana, Pennsylvania and then joined the Princeton Triangle Club. The two met, briefly and incidentally, when Stewart attended a play featuring Fonda’s girlfriend (and later his first wife), Margaret Sullavan. Later, Stewart would replace Fonda in the University Players when Fonda left, heartbroken over his divorce from Sullavan. Like Fonda, Stewart had to convince his reluctant father to allow him to pursue such a risky career.

Fonda and Stewart found themselves broke and desperate for gigs in Depression-era New York City where they shared an apartment with fellow actors Josh Logan (becoming more interested in directing) and Myron McCormick (who was earning the most money of the group through his appearances on radio). Fonda dubbed the apartment Casa Gangrene. It was small, the oven was inexplicably located in the hallway, and the quartet survived largely off of rice. Stewart and Fonda began renting a bar to host hobo steak dinners with entertainment for their subsistence and slowly began earning more through theater. When they had a little money behind them they moved to a better apartment for just the two of them where they built model airplanes. By 1935, both were under contract to Hollywood and so they moved in together in Brentwood.

In many ways, they couldn’t have been more different. Fonda was a New Deal Democrat and agnostic, Stewart a Republican and a believer. Fonda’s screen persona was intractable and distant while Stewart’s was personable and beguiling. And yet, both were good at playing from the depths regardless of the role at hand. From his lightest comedies to his most disturbing roles, Stewart presented multifarious motivations and subtleties in his characters; we are constantly confronted with the slippery workings of a consciousness trying to come to grips with a world it loves but in which security is fleeting. On the surface, Fonda seemed to have a narrower range (although such an assumption is belied by a comparison of, say,

The Lady Eve and Once Upon a Time in the West), but throughout his oeuvre, Fonda presented men held in thrall by the strangeness of their situation — this is epitomized by Fonda’s turn in The Wrong Man but is equally true of his work in most of his roles.

In one sense, Henry Fonda and James Stewart (or Hank and Jim, as they were less formally known) represented two sides of the same American image of manhood: reservedly dependable, heroically human, unknowably recognizable. I contend that both men worked in their portrayals to negotiate the often-vexed relationship between the inner and the outer self, not in some mythic and unattainably heroic mode but rather in the way that the conflict between the interior and exterior experience of the human manifests itself in the average man, whether or not that man is pushed to extremes by circumstance. Indeed, in their finest moments (say, Fonda in Twelve Angry Men and Stewart in

Vertigo) we see how the extremes that test our humanity are not outsized erruptions of mythic force but simply part and parcel of everyday life. We experience such moments as extremes but they are simply part of the warp and woof of the quotidian.

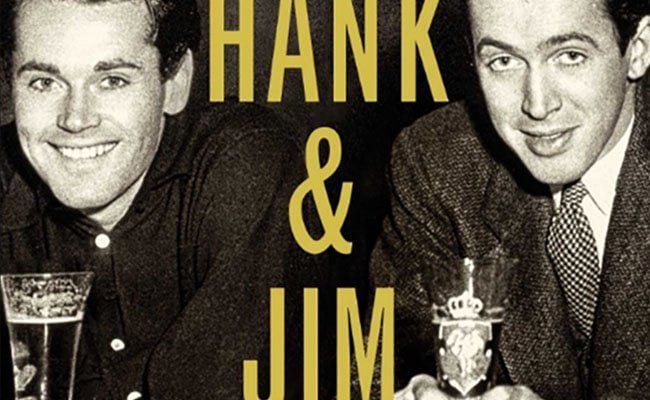

The Film Forum in New York City is hosting a film series on Henry Fonda and James Stewart in conjunction with the release of a new book on the work of these two men and their lifelong friendship, Scott Eyman’s

Hank and Jim: The Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart. This event provides an extended opportunity to again evaluate the distinctions and connections among the performances of these two revered actors over the course of their expansive careers. This essay, through an examination of two of their iconic roles, will attempt in its humble way to articulate something of the understated power they each brought to screen, like a driving current that pulses below the surface without ever fully erupting into view.

Jim

In

The Shop Around the Corner (1940) James Stewart plays Alfred Kralik, the head salesclerk at Matuschek and Company, a leather goods store in Budapest. He spends his days attempting to placate his increasingly and inexplicably petulant boss (Frank Morgan) and verbally jousting with his captious if captivating coworker Clara Novak, played by the enigmatically alluring Margaret Sullavan (this is one of four films featuring Stewart and Sullavan). Meanwhile, Kralik engages in a “lonely hearts” correspondence with a woman that he finds intellectually compelling, emotionally sensitive, and deeply charming. After being fired from his employment without proper cause, Kralik decides nevertheless to keep his appointment finally to meet his epistolary romance for the first time.

When he arrives at the café, he peers in the window only to see that it is Clara that has the carnation tucked into a copy of Tolstoy (the carnation being the designated sign that would reveal her identity). Disappointed and unsure of himself, Kralik engages in conversation with his workplace nemesis on the pretense that he just coincidentally happens to be meeting a friend at that same café. What follows is a masterclass in Stewart’s approach to film acting.

Margaret Sullavan and James Stewart in

The Shop Around the Corner (IMDB)

Kralik and the audience, of course, know something (

the something the crux of the film) that Clara does not. He understands that Clara has fallen in love with her correspondent just as Kralik has fallen in love with his. But Kralik now sees that the woman that drives him to distraction at work, that needles him and provokes him, the woman that has served as an irritant to his quotidian routine and has repeatedly attempted to undermine his increasingly tenuous authority and reputation at a job that he has now suddenly lost, this woman is also the tender, caring, and passionate writer behind the letters that he has cherished, the hopes he has held out for himself, the dreams in which he has invested so profoundly.

What’s remarkable about Stewart’s portrayal here is that he keeps so many balls in the air at once. He recognizes that this is the woman of his epistolary fantasies and so he wants to be gentle with her, wants to woo her. He also cannot forget the petty hostility the two of them feel for each other, the bitterness of which does not simply evaporate — particularly when she’s still hurling insults his way and attempting to clear him from her proximity so as to be unencumbered of his company for the benefit of the date she’s expecting.

But those are just the contradictory aspects of what Kralik understands by recognizing that his romantic pen pal is also his workplace enemy. More revealing of Stewart’s craft is the manner in which he has his Kralik negotiate the cognitive dissonance he experiences in attempting to reconcile the romance to the rancor. He tests her (examining whether this Clara that he knows to be contumacious and cutting can also be the pliant and pleasing persona behind the letters) and teases her. The patterns they have established regarding each other are not so easily let go, particularly as Kralik hesitates to reveal the knowledge he has just attained for fear of her ridicule. He tests her not simply to ascertain if she’s worthy of his love but also, and more urgently, to ascertain whether or not she will be able to accept him as worthy of hers.

Of course, Kralik realizes (and Stewart ensures that we realize) that there’s an element of power here. Kralik has the edge because he has the power of knowledge. Clara sees their conversation as more of the same — the same carping tinged with invective that characterizes all of their interactions. She has no interest in investigating his possible depths (in the way that he examines hers); he’s merely an obstacle to be removed from the path of her ostensibly true, if unknown, love. In this sense, the cutting remarks she makes are par for the course in their relationship for her. But now that Kralik knows that the woman he loves is also the woman he cannot stand, her remarks no longer merely annoy him, they wound him.

Finally, there’s one more element to Stewart’s rendering of Kralik here: Kralik is starting to realize that the doubled-nature of human behavior is not something that appears only in literature. All of the books they allude to in this scene —

Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment, and Madame Bovary — involve the distortions that arise from the conflict of a person’s inner and outer being. In all three cases, the contradictions between inner impulse and outer responsibility, between an inner life based on longing and desire and an outer life dependent upon obligation and duty, lead to disastrous outcomes. The conflictual nature of human existence in these cases seems heroic and catastrophic and thus appealing to a reader, like Kralik, attempting to escape from humdrum quotidian existence.

In seeing Clara as also caught in the dialectic of an inner desirous warmth and an outer pragmatic coldness, Kralik understands that this ontological division of the self is not necessarily (perhaps not at all) heroic and thus, whatever identificatory fantasy Kralik cherished in reading these novels, whatever vision of his own hidden, heroic self he had conjured in relation to them, dissolves into the simple realization that having a divided self does not make one exceptional but is the basic burden of human existence.

Neither Clara nor Kralik are tragic figures on the level of Karenina or Raskolnikov. The love that they have kindled through pen, ink, and stamps is not desperate nor iconic. It happens all the time but somehow, paradoxically, that doesn’t keep it from being special, from being important. Love attempts, at its best, to overcome the division of our self but that division is not mythical but merely all-too-human. It’s deserving of our sympathy more than our admiration; it warrants the gentle acknowledgment of familiarity rather than the awestruck shudder of astonishment.

Very little of the complexity of motivation and bewilderment that informs Kralik’s character at this moment is communicated by the dialogue. Stewart conveys the trajectory of Kralik’s coming to terms with Clara’s bifurcated identity (and his own) through the subtle modulations of the timbre of his voice, the fleeting registrations of his facial expressions, and the discreet gestures of his body. The director Ernst Lubitsch frames the opening of the scene as a two-shot. We see the characters in profile: Clara stiffly seating at a table while Kralik’s lanky form looms hesitantly and unwanted over the vacant seat — the seat that he knows is both reserved for his inner, writerly self (as the author of the letters Clara cherishes) and absolutely denied his outer, bodily self.

As he approaches her, Kralik’s gaze falls toward the copy of Tolstoy’s

Anna Karenina (a book in which, for better or worse, love overrides the entailments and responsibilities of the everyday) and he tries to sound her out on the subject. He voice is gentle and placating; “I didn’t know you cared for high literature”, he softly intones. She sharply rebuffs his advances, which she understandably mistakes for sarcasm, by acidly replying, “there are many things you don’t know about me, Mr. Kralik”.

Lubitsch does not grant us a close-up of Stewart here, so one has to observe carefully. Stewart responds with one of his trademark moves: his head slowly falls into a nod as he mildly grunts “uh huh”; as the nod accelerates he turns his head slightly away from his interlocutor and just as the nod ends, he tightens his lips ever so slightly. The gesture and its corresponding expostulation communicate all at once most (if not all) of the complex of emotions and motivations we outlined above. He registers her refusal of his attempt to speak kindly with her (the “uh huh” is a miracle of embarrassed acknowledgement of rejection combined with an attempt to regroup and redouble his efforts, reinforced by the girding of the loins represented by the tightening of the lips) while the slight motion away from Clara evinces Kralik’s struggle to come to terms with the seemingly impossible task of reconciling the two aspects of Clara.

Kralik soon leans in toward Clara and drops the first hint that he has a secret knowledge of their connection to each other: “There are many things you don’t know about me, Ms. Novak. As a matter of fact, there might be a lot we don’t know about each other. You know, people seldom go to the trouble of scratching the surface of things to get to the inner truth.” During that brief speech, the camera moves to a close-up of Stewart’s face. His expression is determined and yet pleading. He holds Clara’s eyes so deliberately in an attempt to read her every reaction to his words. She comes back at him with one of her best zingers: if she were to look into Mr. Kralik, she sneers, she would find no intellect but rather a “cigarette lighter, which doesn’t work.”

Stewart’s rendering of Kralik’s reaction is simply marvelous. The play of emotions that run across his face are so fluid and yet so marked that it summarizes the situation entirely within mere seconds. He’s hurt but impressed by the sharpness of her wit. His eyes dart from her face to the floor as though he’s calculating the distance that lies between her notion of him as an annoying coworker and her feelings for her beloved correspondent — a distance that he realizes collapses into the figure that stands before her. Moreover, he seems to recognize that the same inventiveness with language and penchant for a turn of phrase that repulsed him in the workplace is precisely what attracted him to her correspondence. All of this culminates in the look of shock and sadness that crosses Kralik’s face later in the conversation when Clara declares that he wouldn’t understand the letters she receives from her love because he’s merely an “insignificant, little clerk”. The darting eyes return but not for a more protracted period, as though he sees the gulf separating her understanding of his inner and outer self growing to outrageous and insuperable proportions.

This scene (and many others could have been chosen for such an examination) reveals at least some of the irresistible and revelatory power of a performance by James Stewart. Often, he embodies a character that is affable and charming while simultaneously reticent and removed. Think of the great moment at the end of

It’s a Wonderful Life when the town bails out the Baileys and Stewart smiles from an almost Platonic distance — as though he’s gratified and blessed by the love of his neighbors but also sees the beautiful pettiness of it all; the grandeur of their devotion to him highlighted by his smallness in the world. Think of the conversations with the six-foot invisible rabbit in Harvey, or, even better, the tale he tells of first meeting Harvey to the doctor and nurses from the sanitarium. Think of the scene of betrayal in Bend of the River when Stewart’s character threatens the rustler with words meant to instill fear and an expression evincing sad inevitability (a sort of amor fati) or the moment of collapse in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington when Smith’s last hope erodes before his eyes (he is falsely convinced that he does not have the support of the people he represents) and yet he determines that he must continue to stand up against what he sees as evil.

In all of these cases, Stewart portrays a man who belongs to but is separate from the crowd, a man who desperately wants to be engaged in the world but is forced to look at it from a distance, a distance often but not always characterized by an affable diffidence. The famous Stewart stutter, the various tics that have been the joy of so many impersonators, the awkward length of that thin body all contribute to the portrayal of a man apart — loved but not completely understood, accepted but not completely assimilated.

Hank

In

The Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) Henry Fonda plays Abraham Lincoln, long before he was president, when he was just getting established in the law in Springfield, Illinois. After having served briefly in the legislature, Lincoln is now installed as a floundering lawyer and, owing to his height and lankiness coupled with his dry wit and penchant for rambling stories, a figure of some mirth among the townsfolk. The film depicts a fictionalized account of a real murder case that Lincoln defended. In this version (unlike reality), the crime involved two brothers who were fighting with a deputy that had been harassing the older brother’s wife throughout the day of celebration. The deputy was stabbed in the heart and both brothers claimed to have been the murderer.

The sheriff insists that their mother, Abigail Clay (Alice Brady) who witnessed the end of the melee, point out which of her sons was the murderer. She refuses and the sheriff carts the young men off to jail. It doesn’t take long for the crowd to become enraged and to decide that they should simply carry out justice on their own behalf by lynching the two men. The drunken crowd forms a mob, fashions a noose, and proceeds toward the jailhouse where they attempt to batter the front door with a log. At this point, Lincoln intercedes, determinedly pushing his way through the mob until he arrives at the doorstep and positions himself between the makeshift battering ram and the jailhouse door that seemed to be on the verge of bursting into splinters.

Henry Fonda in

Young Mr. Lincoln (IMDB)

Lincoln engages in a series of tactics to distract, humor, cajole, and ultimately shame the crowd into giving up on their bloody vengeance and allowing justice to run its course. It is, of course, a classic scene in a revered John Ford film that reveals the director’s sense of pacing, characterization of mob mentality, and the cinematic shaping of a scene through shifting emotion. It’s also the prototypical Lincoln moment that demonstrates his rhetorical verve couched in familiar homily and self-deprecating humor. Moreover, and most importantly for our purposes, it’s a study in Fonda’s preternatural for conveying a carefully calibrated distinction between the inner and the outer man while seeming to do precious little. His body hardly moves, his expression rarely changes (it registers none of the complexities we examined in Stewart above); he’s free from all of the typical “actorly” modes of conveying emotion and even free from the idiosyncrasies that make Stewart so disarmingly charming.

Lincoln perches himself in the doorway, his arms grasping the doorjamb at a diagonal angle. Fonda holds his face in an impassive, unreadable expression. It’s nearly blank altogether, even the determination evinced in his march through the crowd is gone. We don’t get the sense that Lincoln is concerned or scared or particularly angry — he’s simply inscrutable as though he watches the events from some untold distance. When the crowd refuses to heed his calls to order, he thrusts the log away from him with a kick. His arms fall to his side and he declares he’s not there to make speeches but is willing to fight any man willing to take him up on the offer. The mob bursts into laughter at the incongruity of the gesture. Lincoln spits into and rubs his hands together in mock anticipation of a brawl. But he never smiles, he never mugs to the crowd. Is he serious or is he attempting to amuse the audience?

He taunts one member of the crowd to fight him but without much of a real threat, the man backs down and recedes into the anonymity of the mob. As the mob tries to return to battering the door, Lincoln moves on to another tactic. Now he jokes with the crowd more openly. “Some of you boys act like you want to do me out of my first clients,” he jibes. He then assures them that they may be right and maybe the boys do deserve to hang. Then he hangs his head in mock humility and claims that with him on their case, it “don’t look like you’ll have much to worry about on that score.” Fonda allows himself to crack the slightest smile here but again he’s largely impassive. A lesser actor — hell, pretty much any other actor — would ham up the line just a bit in to demonstrate, if nothing else, Lincoln’s ability to connect with crowds even in moments of high tension. But Fonda does nothing of the sort. He doesn’t even allow the moment to feel like it’s building to some culminating point; he simply moves on to the next tactic — a sermon on the evils of men taking the law into their own hands — with the same impassivity, the same distance that he embodies throughout the scene.

What’s truly remarkable about Fonda’s performance in this film and as exemplified by this scene, is the amount of innate, burning resentment he brings to the character of a youthful Lincoln. All other cinematic and biographical accounts that I can summon to mind depict the young Lincoln (and often the older Lincoln, as well) as an affable, eager man who may be guilty of a false humility in his meticulously hewn “man of the people” manner of speaking (thus hiding his hard-won education and perspicacious intellect) but is ultimately a deeply genuine, pragmatic, and caring figure with a profound fellow-feeling that he shares with the members of his community. He may be willing to play up his supposed inadequacies to make his position more palatable and make himself more relatable, but this is not a display of cynical manipulation.

Fonda, however, finds something more adamantine and recalcitrant at the heart of Lincoln’s inner life that stands in a starkly ironic contrast to his gregarious public persona. Fonda’s Lincoln seethes with a barely restrained disdain for his fellow man. I’m not naïve enough to believe that everyone will simply accept this reading of Fonda’s portrayal. But watch that scene again and pay heed to Fonda’s demeanor. He knows he’s dealing with children in the guise of grown men and he speaks to them in that manner. He knows they must be entertained in order to be persuaded and so he makes light of the situation despite its overwhelming gravity. But while he does it, he never betrays his emotions, whatever they may be. His impassivity is a calculated refusal to identify with the moment. By seeming so removed, he maintains control.

And yet behind that control lies resentment. Fonda’s Lincoln accepts that he must play these roles to make people do right but he is angered and embittered by the fact that he is the only adult in the room at any given time. He’s outwardly affable but barely disguised behind that affability lurks a bitter indignation. Notice that Fonda never offers the cinematic audience any direct clue as to the relative truth or falsity of either side — the inner or the outer man. The question that lingers in my mind is: is this seeming conflict between the kind exterior and resentful interior the engine that drives Lincoln’s character for Fonda or is it merely part of the act Lincoln must maintain to get his way? I don’t think that is ever made clear in the scene because Fonda doesn’t seem to see any distinction between the two and therefore sees no reason to inform the cinematic audience of the truth behind the façade. There is no truth here, merely façade.

Hank and Jim

As is so often the case in his films, Fonda presents a tabula rasa, a blank slate on which you can draw your own understanding of the scene, its commitments, its entailments. In this sense, and in contrast to Stewart, Fonda is one of the least giving (or least forthcoming) actors of the screen. Stewart provides layer upon layer in his performances, he invites the audience into his understanding of the world within the film. He becomes a conduit for our understanding, like a guide that indexes points of interest, areas of concern. In a Stewart film, we adopt his welcoming (if still diffident) gaze onto the structures of the cinematic landscape. Fonda is entirely different. He stares back at us in a Sphinx-like emptiness. His glare is a void that makes a demand upon the audience without ever clarifying the terms of that demand.

A somewhat glib neo-Platonic take on the aesthetics of cinema would have it that film is glimmering light that cuts through and fades into obfuscating shadow providing a glimpse of a truth that cannot be pinned down with the epistemological clarity of the conceptual; it’s the revelation of a truth that cannot be seen face to face but only through a glass darkly. In that metaphor, Stewart focuses our attention on the penetrating quality of the light (the act of looking with the actor, of seeing the opportunities of the world in their joyful ambiguity) while Fonda represents the dark, unknowable core of shadow, the dark side of the moon that lies behind what little is revealed and gives the revealed its cultic power to overwhelm and enchant. Stewart and Fonda, the light and the void: these are the dialectical partners in the unfolding of truth in cinema, a truth predicated on the belief that the vying of the inner and outer man is not a liminal or a peripheral event to be experienced only by the heroic in outlandish moments of fated glory. Rather each of us, at every instant in our small ways, must reconcile the conflicting impulses of our deep-seated longings and our social obligations. These are not moments

in extremis but rather it’s part of the ontology of our everyday lives. What Fonda and Stewart managed with such breathtaking agility was to reveal the heroism that lies at the heart of the average, the vexed riven discontent that informs our seemingly unified selves.

* * *

The Film Forum in New York City presents “

Hank and Jim“, a festival featuring the films of Henry Fonda and James Stewart from 27 October to 16 November. The book Hank & Jim: The Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart by Scott Eyman (published by Simon & Schuster) will be available for sale throughout the series and the author will introduce screenings on 27-29 October. Many wonderful films will be presented, including those mentioned in this essay as well as Rope, Drums Along the Mowhawk, The Grapes of Wrath, Jezebel, and Destry Rides Again.