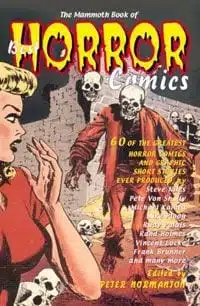

Long before the advent of slasher flicks and torture porn, the youth of America was getting its fix of transgressive violence through the horror comic. This subgenre in the comics industry was especially popular beginning in the 1940s. It peaked in the early ‘50s right before a Senate Subcommittee put a Comics Code in place in 1955. It’s not surprising that The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics, edited by Peter Normanton, devotes its largest section to these Golden Age horror comics, those written before severed heads and gouged eyes and rotting corpses were declared off-limits in the panels of children’s comic books.

The Mammoth Book of Horror Comics contains many good strips, and the best of them come from the pre-code period. Well-drawn, and full of violent action and tongue-in-cheek humor, what gives these strips their special kick is their willingness to cross the line into truly gruesome territory. The stories often involve torture; in He writer Rudy Palais rips off Edgar Allan Poe by creating an innkeeper that straps his guests beneath a sword attached to a pendulum. A more unique tale is Terror of the Stolen Legs from Dark Mysteries, a first-rate yarn set at a concentration camp where a deranged Nazi doctor is experimenting with bringing corpses back to life. After experimenting on a young man he perceives as a romantic rival, then murdering him, he is haunted by the reanimated corpse. His solution is to exhume the body and saw off its legs.

What works about these grim miniatures is that there are no ulterior motives at work, no deeper sub-text, no aspirations at art; they merely exist to frighten and surprise the reader, and if they can’t do that, then they’ll try for the lowest of shock tactics. There is also a fair amount of gallows humor present in their panels — they don’t take themselves too seriously. This isn’t always the case with Normanton’s selections from more recent years, many of which are either too convoluted and artsy, and some of which are downright terrible, including two comic strips that use a mix of photography and art. The model/actors used in these bizarre photo-montages manage, through nothing more than still photography, to turn in terrible performances. An impressive feat.

There are some keepers from after the code was instigated, including a particularly sick little tale called Fatal Scalpel, first published in a comic called Weird in 1966. A plastic surgeon, driven mad by his wife’s infidelities mutilates both her face and her lover’s face, then blows his own brains out, leaving behind a will that stipulates that in order to get all his money, his wife must marry her lover. The last panel shows their side-by-side faces, noses inside out, mouths grotesquely stretched, two hideous monsters forced to spend the rest of their lives together.

Ultimately, however, this anthology, while not a waste of time, is in no way representative of the “best horror comics” that it promises. This is because, for obvious reasons, Normanton could only select from the more obscure publishers, both then and now. As he states in his introduction: “You won’t find anything by Marvel, DC, Warren or EC in these pages — they have published their own collections — but what you will find is a rich array of talent spanning over sixty years.” It’s clear that the editor realizes the limitations that were placed on him.

The biggest omission is not having anything from the comic book publisher EC, the house that in 1950 introduced the title Tales from the Crypt. Under the leadership of artist and editor Al Feldstein, EC created the blueprint for horror comics, while also inevitably bringing about the censorship laws. Having an anthology of horror comics without anything introduced by the Crypt Keeper is like having a festival of Westerns with nothing by John Ford.

Another distinct problem with the book is its lack of color illustrations — a few cover reprints would have been nice — and its size, which, at about six-by-nine inches, means the original pages have been shrunk, making the art and the text that much harder to see. It was a choice made, I’m sure, with the budget in mind, but the true joy of comics is in the illustrations, and it was a poor choice — the book would have been better off in a larger format.

If you’re a fan of horror comics, or horror in general, then you’re bound to find plenty in this anthology worth reading. And if you find yourself slogging through one story then you can simply skip to the next — it is both the advantage and the limitation of all anthologies. And if nothing else, then The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics will almost definitely whet your appetite for more disturbing tales from the halcyon days before the Comics Code came along and told horror to clean up its act.