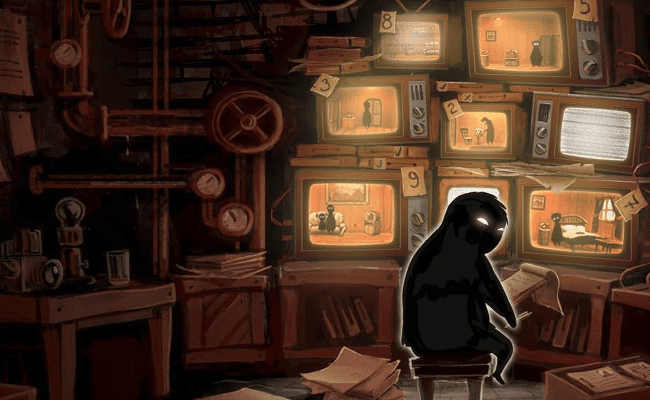

The trailer of Beholder asks of its player, “What would you be?” This question is asked within the context of a game set in a totalitarian state in which the player takes on the role of the landlord of a rental property who has been called on by the state to spy on his renters.

The question, of course, raises the central concern of the game. Will you follow the dictates of the state and take on your duty to engage in surveillance activities of your fellow citizens or will you try to fight the system from within, attempting to protect the freedoms and privacy of these potential victims of the state?

Such binary morality systems are common to games these days, and it seemed obvious to me before playing the game that the only viable option for approaching the game would be in some kind of covert revolutionary role. After all, I despise the idea of a surveillance state. I dislike the idea of rules that serve to perpetuate a nanny state, determining the choices and thoughts of its citizenry as if paternalism or moralism is the role of government, not the protection of individual liberty.

However, in practice, the game complicates the idea of adopting a clear black hat or white hat role within the context of its fiction and its game systems.

I suppose this should come as no surprise, since games like Papers, Please already exist. Admittedly, I haven’t played much of that game, but I understand its premise, which is that you take on the role of an immigration inspector at a border crossing and have to make hard decisions in that role. Papers, Please is interested in raising thorny ethical questions concerning the decisions that you make in who to allow through your checkpoint, given the sometimes dire circumstances that you can foresee occurring. For example, the game asks you to consider what will happen if you don’t let a family in a desperate situation through despite improper paperwork, or worse still, perhaps, what the equally dire circumstances of allowing someone who appears troubling or dangerous through who still checks out from a bureaucratic perspective.

Beholder makes these questions more personal, though, by encumbering the protagonist with reasonable responsibilities of his own. Carl Stein is a man with a family, with bills to pay — in other words, a man with good reasons to follow the dictates of his employer, the State. While it is easy enough to assume one would stand for principles in the face of authoritarianism, once your daughter is sick and in need of medicine or one’s son is about to get kicked out of school unless you come up with some quick cash, protecting a principle seems less practical or even less important than keeping people that you love out of danger.

The interesting thing about Beholder, then, is the way that it makes one look at the idea of defending the moral good within a legitimately impractical and unforgiving situation. Your daughter will die if she doesn’t get medicine to treat her lung disorder, so what difference does it make that you need to hang some propaganda posters in order to reach your next payday?

People often wonder how others could stand idly by as the Nazis razed Jewish ghettos or how others could turn a blind eye as Stalin and Mao purged their respective nations of perceived dissidents and undesirables, and Beholder confronts those questions quite directly with its simulation of working within such a system. None of those people were in any way actually idly standing by. These were people that were working, working in a normal way, trying to better the lives of themselves and their loved one. Because they had other people close at hand and dearly loved them, they didn’t want to put any of that in jeopardy by rocking the boat or biting the hand that fed them. The game seems to argue that it is people’s instincts to concern themselves with those that they are responsible for (a noble instinct) that makes them feel that they have to go along with things that they don’t necessarily want to go along with.

Beholder injects humanity and love into what could be a dry political simulation and shows how disastrously human need and emotion clashes with political philosophy and a desire to be good when such a situation is seen not in the abstract, but, instead, in a very distinctly human way. It’s a thoughtful game about darkness and why sometimes we let darkness spread out of compassion and a desire for safety and comfort that simply cannot last, despite our most noble intents.