F. Scott Fitzgerald maintained that there are no second acts in American lives. He never met David Carr.

In his shocking, often spellbinding memoir, Carr, media columnist for the New York Times, revisits his nightmarish opening act — as a cocaine addict in Minneapolis in the ’80s. Carr was not simply a Hoover with a bad habit. He was a man on fire, the kind that party animals back away from slowly, shaking their heads in dismay.

He was introduced to the drug on his 21st birthday, going into a restaurant bathroom to sniff it: “It was a Helen Keller hand-under-the-water moment. Lordy, I can finally see. Cold fusion, right there in the bathroom stall; it was the greatest feeling ever. My endorphins leaped at this new opportunity, hugging it and feeling all its splendid corners. My, that’s better.”

Over time, he progressed to smoking crack and, finally, to injecting the drug every 20 minutes. He went through five rehabs without putting a dent in his chemical dependency. “Although I failed to get the hang of some of the fundamental tenets of recovery, I believed I was an asset to every treatment center I wheeled through,” he writes sardonically.

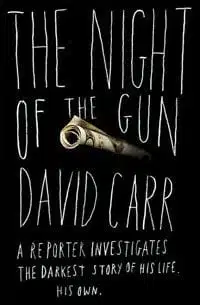

But The Night of the Gun has an unusual framework that sets it apart from other I-survived-addiction manuals. Carr used his reporter’s tools to document his past, interviewing friends, family, dealers, lawyers, bosses and other people who witnessed his descent into depravity. Their testimony proved again and again that his past was far nastier than his recollections of it. The book takes its title from a frightening episode when Carr drew a gun on a friend — and remembered it the other way around.

As painful a process as this reporting was for Carr, he’s smart enough to realize that it was no fiesta for the people he hunted down, either. “Reporting can be obnoxious no matter who is asking the questions about what, but all this was the more so because the reporter wanted to ask deep, probing questions about himself. Even for me, it was a new level of solipsism.”

After a long, steep run, Carr finally hit bottom in 1987. He had been living with a woman who was a seriously connected dealer (which explains how a freelance journalist was able to indulge in such an expensive habit). She got pregnant, never quit using, and gave birth to preemie twins.

One cold November night, Carr left the twins in the back of his car while he stepped into a shooting gallery for a quick boost. When he emerged several hours later, he could see the tiny girls in their child seats in the back seat, exhaling clouds in the frigid car. Carr found he had just crossed a line that even he could not live with.

The girls went into foster care while their father clocked six months in a rough residential treatment center, gaining 10 pounds a month, in part by shoveling down mounds of instant potatoes liberally larded with butter.

Upon emerging, he began walking the narrow path while desperately pursuing his journalism career and fighting for sole custody of the twins. That last goal proved especially challenging.

“So other than being addled from an unspeakable habit, a little smelly, and a touch on the amazingly obese side, I was good to go. Ready to star in one of those car commercials where the kids crack wise in the backseat while dad says something sage and knowing into the rearview. Except I didn’t have a car. And the kids did not belong to me. I had never married their mother or established my paternity. I had no insurance, and I had not paid taxes in several years.”

The Night of the Gun is written in an exceptionally elegant and intelligent manner. Carr cites sages like William Blake and quotes everyone from Proust to Vonnegut.

The taped conversations with figures from his past are unsurprising. But Carr’s meditations on his experiences are extraordinary. This is an insightful book about addiction and recovery, but it is also a fascinating study of memory and the ways it insulates us from past pain — even when we are the source of that suffering.

There is a disquieting personal twist at the very end of the book that muddies the waters, forcing the reader to question Carr’s chesty candor. It turns out there were cards he wasn’t showing.

Despite that late corkscrew, The Night of the Gun remains a searing and penetrating memoir. It’s the cautionary tale of a real-life Humpty Dumpty who was somehow able to put it all together again.