When Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, it sparked a lot of controversy; after all (and as Time contributor Kostya Kennedy wrote last December), he was “the first American to win the prize since Toni Morrison in 1993 and, more significantly, he became the first songwriter, from any country, to win it ever.” Many people cried foul because to them, several more deserving (and legitimate) authors had yet to receive the award — intrinsically implying that Dylan, like all musicians, is merely a performer — while others championed the choice as a reflection of Dylan’s singular lyrical merit and staggering influence on cultural consciousness and boundless artistic expression. Either way, it forced us to reconsider a powerful question: Is popular music merely entertainment, or are there more complex and meaningful things going on beneath the surface?

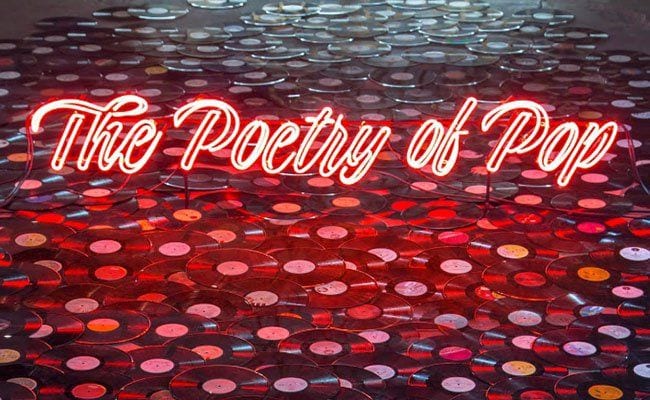

In his latest book, The Poetry of Pop, professor of English Adam Bradley goes into exhaustive detail to convince readers that “pop songs are music first, but they also comprise the most widely disseminating poetic expression of our time.” He explores a vast array of styles and eras — stretching back a century or so — to conclude that while the work of, say, The Rolling Stones, OutKast, Marilyn Manson, Christina Aguilera, and George and Ira Gershwin are vastly different, they’re also “united in their exacting attention to the craft of language and sound.” Although his writing can be verbose and filled with jargon at times, there’s no denying how much research and care he puts into arguing that, through “rhythm, rhyme, figurative language, voice, narrative structure, style, and more”, this music “reflect[s] the political and cultural climate[s]” that affect us each day.

The term “pop music” can be divisive, so Bradley wisely begins by refuting “assumptions that all pop is bubblegum music intended for preteens, that it is mass-produced and indifferently crafted” and clarifying that he sees it as “a broad descriptor that encompasses everything from Broadway musicals to country ballads, from obscure soul sides to Billboard Hot 100 hits… pop is inclusive, multiracial, and global in its appeal.” Basically, the only thing it doesn’t’ relate to is classical music, and he even refers to Eric Weisbard’s defense (in Listen Again) that because other genre classifications — “folk, jazz, blues, rock and roll, soul, hip-hop” — are “more confining than illuminating”, it’s best to use the umbrella term “pop music” for “all that is heard, loved, and yet rarely ennobled.” Not only does this section provide a clear lens through which Bradley is analyzing his subjects, but it also shows an academic prowess for preemptively addressing counter arguments and relying on weighty sources for outside support.

One of the earliest chapters here, “Listening”, is also one of its most interesting and in-depth. In it, he claims that while closely reading lyrics is “more commonly associated with poetics”, it’s just as important to be aware of how said language “lives in the air, evading efforts to capture it in print” because “both music and singing have far more direct access to emotions than do words alone.” Naturally, he applies these general assertions to several specific songs, including Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”, Stevie Wonder’s “I Was Made to Love Her”, and George Michael’s “Everything She Wants”; he even compares Emily Dickenson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge over Troubled Water” in that both invite the audience to become one with the speaker in terms of compassion and appreciation.

A bit later, he lauds Blues Traveler’s “Hook” as “a song that lampoons pop music’s formulaic structure even as it exploits that structure… [it’s] catchy, both melodically compelling and ironically self-knowing”. Afterward, he examines how Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” utilizes rhyme, repetition, and vocal cadences with far more subtle ingenuity and purpose than casual fans — and by association, the mainstream media — might expect. In doing so, he reveals how much attention to wordplay and meter (things we typically associate with poetry) is actually afoot within even the most seemingly superficial radio hits.

“Story” also proves to be immeasurably insightful, as it attests that “the epic poem and the ballad comprise part of the narrative heritage of the contemporary pop song” because “song narratives share a great deal with written and spoken narratives, but differ in ways that complicate character, setting, time, and the rest of the constitutive elements of a storyworld.” In addition to discussing how Joni Mitchell’s “The Last Time I Saw Richard” and Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide” approach factors like action, time, and setting, Bradley exposes how ‘60s icons like The Beatles and challenged thematic traditions; for instance — and as Steve Turner observes in A Hard Day’s Write — “Fewer than half the songs on Revolver were about love. The rest of the songs on this album ranged from taxation to Tibetan Buddhism.” Obviously, there’s a lot more to “Story” than this (including a section on how we hear music), and it’s all quite wide-ranging and thorough.

That said, The Poetry of Pop can be ntensive at times, with Bradley preferring unnecessarily wordy and erudite enlightenments over concise and welcoming ones. Of course, the entire purpose of the book is to pick apart popular music for overt and/or hidden systems and purposes — as well as make connections to literary conventions and criticism — but as always, delving this microscopically into things can yield extraneous and tedious results. Although Bradley’s intended audience is scholarly in terms of musical and poetic histories and vocabularies, his readership may actually encompass a more, well, “popular’ crowd.

Even though it can be a chore to get through, The Poetry of Pop is a testament not only to Bradley’s knowledge, dedication, and skill as a music fan, academic, and writer, but also to the power, craftsmanship, and worthwhile intent of even the most ostensibly thin tunes. It establishes strong and unique links between music and poetry / literature throughout, which serves two great purposes: to further substantiate already revered gems and to effectively legitimize commonly undervalued genres, artists, and tracks. In general, it does a remarkable job of proving that singer/songwriters and other musicians like Bob Dylan are, as Shelly said of poets nearly two hundred years ago, the “unacknowledged legislators of the world”.